The U.S. Navy commissioned its newest ship, the San Antonio-class amphibious transport dock Richard M. McCool, in a Sept. 7 ceremony at Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida.

With the vessel’s crew and several family members of the ship’s namesake in attendance, Navy Secretary Carlos Del Toro lauded the bravery of McCool and commended the on-hand “sailors and Marines [for bringing] this incredible warship to life in service to our nation.”

“Capt. McCool’s leadership in the face of grave danger and his acts of heroism to save the crew and the ship our nation entrusted to him are indeed an example for all throughout,” Del Toro said.

It was during the bitter World War II Battle of Okinawa that the courage of Richard McCool would be on full display.

Aptly dubbed the “Typhoon of Steel,” the operation was launched to wrest the island from Japanese control, sever the last southwest supply line to mainland Japan and open to island for use by American medium bombers.

On April 1, 1945, approximately 60,000 U.S. Marines and soldiers of the U.S. Tenth Army waded ashore from landing craft onto the beaches of Okinawa, Japan, in what would be the largest amphibious assault of the Pacific Theater.

Though the American landings were at first largely unopposed, the fights that ensued would prove to be some of the war’s most horrific.

“By the time Okinawa was secured by American forces on June 22, 1945, the United States had sustained over 49,000 casualties, including more than 12,500 men killed or missing,” according to the National WWII Museum.

“Okinawans caught in the fighting suffered greatly, with an estimate as high as 150,000 civilians killed. Of the Japanese defending the island, an estimated 110,000 died.”

Particularly brutal during the chaos on Okinawa were the seemingly interminable attacks by Japanese kamikaze pilots, who, due to the sheer size of the U.S. amphibious assault, had their pick of Navy ships sitting off the island’s coast.

On April 6, a total of 34 U.S. Navy ships off Okinawa were hit by kamikazes in the first of 10 major attacks. The incessant onslaught lasted five hours and featured a staggering 355 kamikazes and more than 300 fighter escorts.

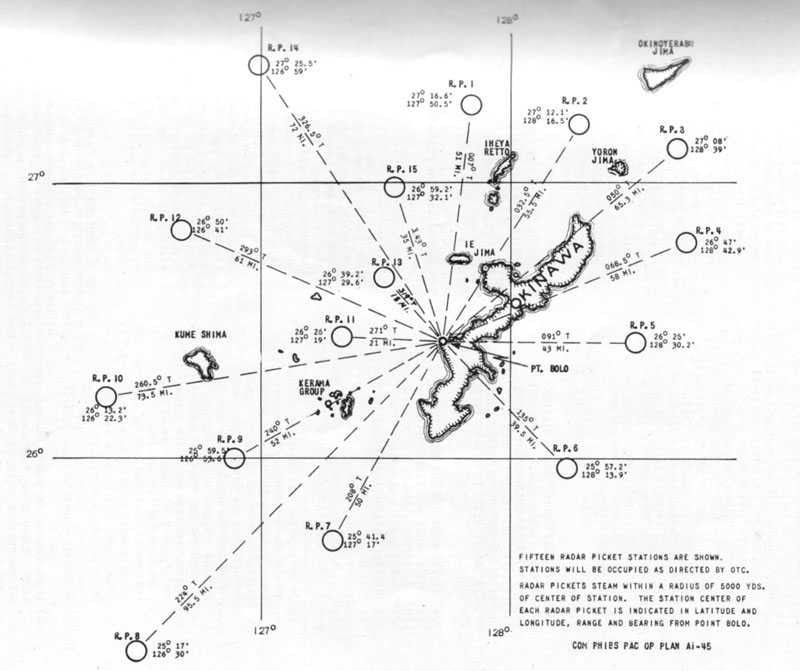

To stifle the ongoing attacks, the U.S. encircled the island with 15 radar picket stations. Each station featured at least three radar-equipped destroyers, which could detect imminent attacks, and four LCS ships that would act as the destroyers’ guards and shoot down incoming planes.

On May 10, 23-year-old Lt. Richard Miles McCool Jr., then in command of LCS-122, settled in off the coast of Okinawa.

“Arrival in Okinawa was very warm, with air raids every few hours of every night, and sometimes in the day,” McCool wrote in his ship’s history log. “The assignment consisted of anti-suicide boat patrol and radar picket patrol. ... On the 29th of May [LCS-122] shot down one enemy aircraft and was given credit for an assist on another.”

Exactly one month after arriving at Okinawa, McCool and the crew of LCS 122 were on picket duty when the nearby destroyer USS William D. Porter — the same “Willie D” that almost killed President Franklin D. Roosevelt — was severely damaged in a kamikaze attack.

The destroyer initially evaded the Japanese “Val” dive bomber, but the Willie D’s string of bad luck would soon continue.

Though the Val appeared to splash harmlessly nearby, the submerged aircraft ended up beneath the destroyer and promptly exploded.

“The ship leapt out of the water and fell back; her power out, steam lines burst, and fires breaking out,” according to the National WWII Museum. “Although the ship’s crew fought valiantly after three hours, the commanding officer ordered the ship abandoned. As the order came down, just under 300 crew had to evacuate. Performing her duty as a ‘pallbearer,’ LCS-122, with McCool in command, worked to rescue the ship’s crew. Incredibly, there were no fatalities.”

The following day, however, McCool and his crew were not so lucky.

As he recalled in an interview with the Congressional Medal of Honor Society, the LCS ships were sitting in a diamond formation to provide a screen for the destroyers when three Japanese Val dive bombers were spotted closing in fast.

The ship’s anti-aircraft guns erupted as the first kamikaze came in low — so low, in fact, that McCool “was afraid that the people in the 40mm gun mount might have been hit by the wheels,” he recalled.

The shot-up aircraft “passed approximately eight feet above the forward end of the deck house and splashed on the port side not more than 100 yards away,” the after-action report stated.

“Attention and all fire was immediately shifted to the two remaining oncoming planes,” the report added — the second of which did not miss.

As sailors tore into the remaining bombers with a wall of gunfire, the second Val, smoking after hits by one of the ship’s 20mm guns, slammed into the vessel’s starboard side at the base of the conning tower.

“Fire immediately broke out throughout the amidships section of the ship, while pyrotechnic and 20mm ammunition started exploding,” the after-action report stated. “A bomb carried by the plane passed through the ship, emerging on the port side. It exploded as it hit the water, showering the port side with shrapnel.”

“I don’t really remember much of what was going on after that,” McCool recalled. “When I finally came to, I was the only person there in the conning tower. ... I shimmied over the port side of the conning tower and dropped onto the deck from there.”

Peppered with shrapnel and suffering severe burns, McCool refused medical treatment and rallied his men to fight the flames quickly engulfing the vessel.

McCool “proceeded to the rescue of several trapped in a blazing compartment, subsequently carrying one man to safety despite the excruciating pain of additional severe burns,” his Medal of Honor citation reads. “Unmindful of all personal danger, he continued his efforts without respite until aid arrived from other ships and he was evacuated.”

For his actions, McCool was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Harry S. Truman in December 1945.

His full Medal of Honor citation can be found here.

McCool remained in the Navy until 1974, when he retired after 30 years of service at the rank of captain.

Richard M. McCool passed away at the age of 86 on March 5, 2008, in Bremerton, Washington, with his wife and children at his bedside.

He is buried at the U.S. Naval Academy Cemetery in Annapolis, Maryland.

Claire Barrett is the Strategic Operations Editor for Sightline Media and a World War II researcher with an unparalleled affinity for Sir Winston Churchill and Michigan football.

J.D. Simkins is the executive editor of Military Times and Defense News, and a Marine Corps veteran of the Iraq War.