In 1993, Marine colonel and reservist Donald E. Marousek scratched away at his life story in a notebook in slanted, left-handed penmanship.

His daughter, Susan Perry, of Anaheim, California, always had encouraged her father — and personal idol — to record his most precious memories for her children, and grandchildren, but assumed he had never completed the assignment.

After Marousek died in 2013, just weeks shy of his 93rd birthday, his children found a black three-ringed binder with chapters typed up by their mother, Betty, in a bedroom drawer as they prepared to sell the family’s Redondo Beach house.

Initially, the family was hesitant to share Marousek’s private pages because he was so faithfully loyal to the Marine Corps and never called attention to himself. They also feared that he may have harbored survivor’s guilt after losing friends in several wars, but agreed that his memories send a valuable message to the generations about loyalty, brotherhood and the service that defined him.

“My father wouldn’t even stand when veterans were asked to identify themselves at stadiums and veterans’ events, because he never engaged in combat,” said Perry. “He didn’t feel like he merited the attention, having known so many who made the ultimate sacrifice.”

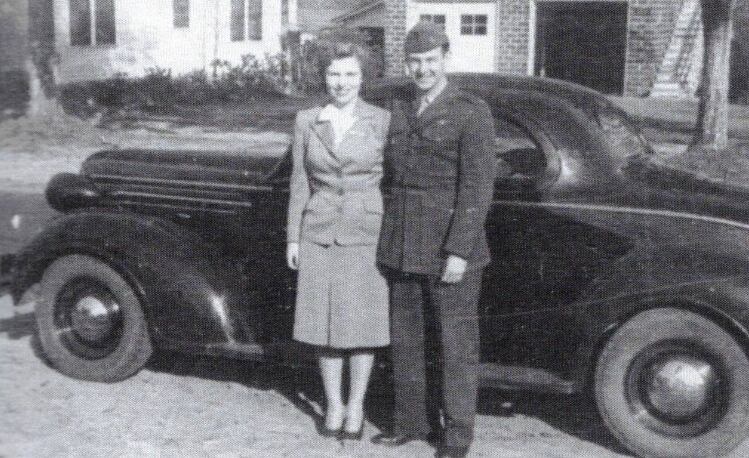

After “Moose” Marousek received his commission as a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps, he and Betty married on Nov. 15, 1944. During the war, Marousek was an instrument fight instructor at Naval Air Station Whiting Field near Pensacola where his all-time favorite aircraft was the F4U Corsair. He was also stationed at Naval Air Station Opa Locka in Miami where he flew TBF Avengers and made his first tailhook landing in October 1945.

From 1946–1950, the couple returned to New Jersey where the combat pilot taught woodworking and coached varsity baseball at Park Hill High School and reported for duty in the reserves.

In 1950, he wrote, “Our squadrons of F4U Corsairs (232 out of New York and VMF 235 out of Boston) were the first Marine squadrons activated for the Korean conflict.”

Marousek initially was stationed at Kaneohe, Hawaii, where his squadron elected him as signal officer aboard several carriers. His final hitch was a desk job as a Stearman flight instructor, specializing in night flight training.

Marousek mustered out of the service on Sept. 10, 1952, making his last flight into Wright-Patterson field in Dayton, Ohio, and went on to have a successful career in the sales and manufacturing of precision tools for planes.

But the Marine Corps always was a part of his life.

A home movie narrated by Marousek, features his Red Devils squadron flying Corsairs for the “Flying Leathernecks,” starring John Wayne at Camp Pendleton, California.

A memoir discovered

In Marousek’s family memoir, he described how he was born in 1920 on the kitchen table of the two-story frame house illuminated by the “last streetlight” on Havemeyer Avenue in the Bronx.

His baby pictures are woven into the memoir with portraits of his grandparents (August and Anna Marguerite Schroder), first-generation German and Czech immigrants, standing beneath the pin-striped awning of the grocery store they owned in the Bronx near trolley lines, and the barn where the family stabled their horses, “Peaches” and “Astor,” which pulled a wagon transporting produce from nearby farms.

The full-bird colonel recalled childhood summers where the family stayed in the old salt-box beach cottages on Long Island, and visits to the Jersey shore where he rode his first rollercoaster with his mother on Coney Island.

Marousek attended Wittenberg University in Springfield, Ohio, where he played baseball and basketball, and courted Betty, who rode in the 1937 Dodge with the rambler seat and lived nearby in Dayton, Ohio, where her family remembered the days when Orville Wright sold bicycles to “crazy people who thought they could fly!”

When sports went to war

War shaped Marousek’s destiny.

Several months after the 1941 Pearl Harbor attack, Marousek enlisted in the military with dreams of becoming a Marine.

He began civilian training school at Syracuse University and Amboy City/Onondaga airport, where he got behind the controls of a Piper Cub airplane and instantly was hooked on flight.

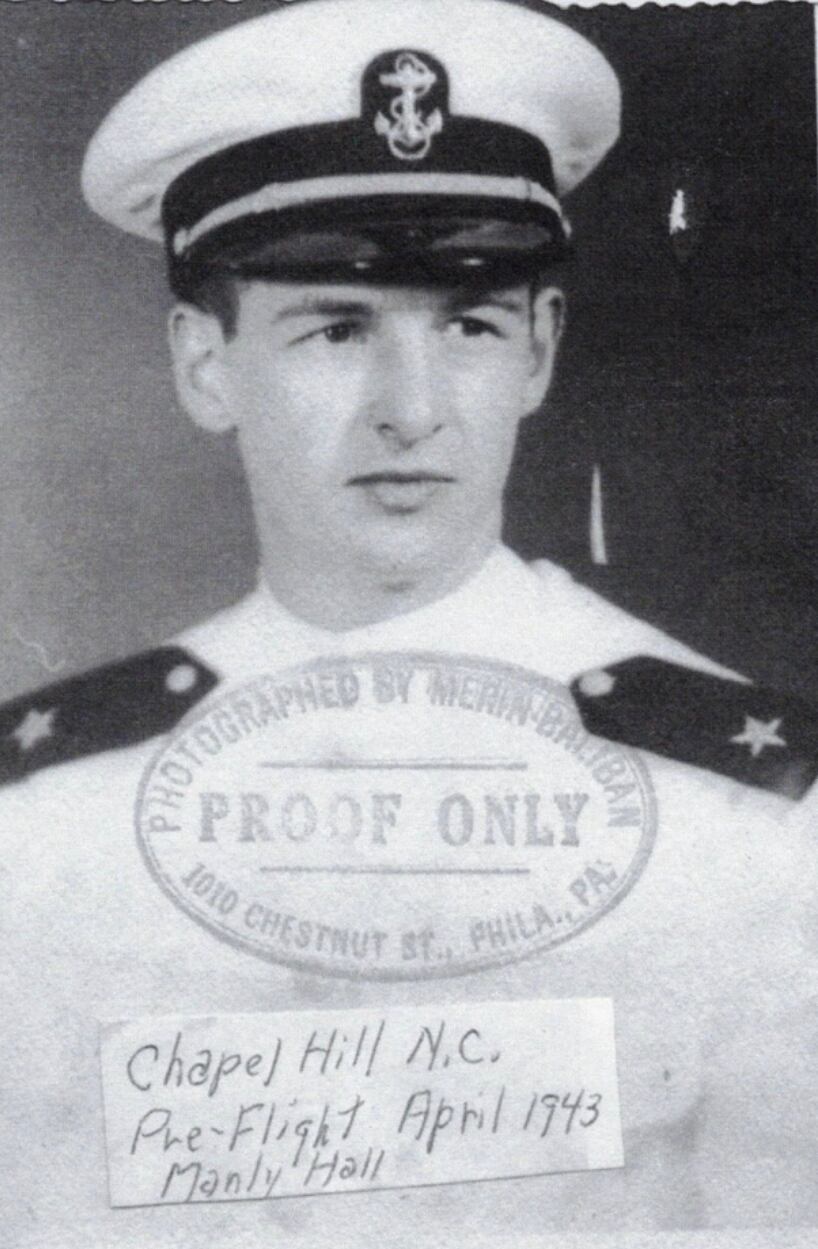

In March 1943, his next stop was the V-5 Naval aviation pre-flight school in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, a brutish camp where cadets were conditioned to advance to the next phase of real, in-flight training.

Competitive sports like football, basketball, boxing and wrestling were repurposed combat-style. Fouls were not called in competition, protective gear was slight, and America’s toughest coaches were tasked to extract “killer instinct” from sea-going pilots.

Officers who coached “pre-flight” fliers included the Crimson Tide’s Paul “Bear” Bryant and Notre Dame’s “Four Horseman” Jim Crowley, UCLA basketball’s John Wooden, world-champion wrester Don George, and Larry Snyder, Jesse Owens’ track coach at Ohio State. Detroit Tiger and Baseball Hall of Fame second baseman Charley Gehringer manned pre-flight baseball diamonds while world-champion boxer Jack Dempsey laced up his gloves for demonstrations and future president Gerald Ford jumped into rings to toughen up cadets like young George H.W. Bush.

In today’s world, pre-flght coaches might include athletes such as NFL quarterback Tom Brady or Lakers basketball phenom LeBron James.

The social media whirl generated by these personalities would be irresistible. But surprisingly little was reported about this supreme era of athletic volunteerism because pre-flight trainees were too exhausted, bruised and maybe even a little too bashful to brandish reports on the daily grind in diaries and letters home to Mom and Dad.

Marousek “described (pre-flight) as incredibly difficult and one of the best things that ever happened to him,” said grandson Andrew Bermond, who keeps his grandfather’s leather flight jacket on display behind glass in his office. “And he considered it a great honor to be one of two non-MLB players to have made the Navy baseball team.”

Because causalities were fierce at pre-flight, the Navy would not let just any reporter watch ambulances cart men off fields with broken limbs. Fifty years after LIFE magazine toured the Chapel Hill, North Carolina, camp, Marousek reflected on the intensity of a typical pushball game when his battalion was asked to show reporters how America was defeating the enemy.

“It was March 1943, when the train took us to Chapel Hill—the University of North Carolina, the ‘Tarheels’—one of the three Navy preflight schools throughout the United States, but by far the most prestigious. This was the most organized, regimented, and disciplined operation I have ever witnessed. Everything was run by timing -- not a wasted moment. As one class of cadets arrived for an event, the earlier class was just leaving. It was here that you developed your mind as well as your body. Classes in aircraft and ship recognition, Morse code, and blinker code, aerology, navigation--both dead-reckoning and celestial -- and training films of all sorts, but not an airplane in sight!

Then on the physical side was wrestling, boxing, basketball, and soccer (with no rules), marching, push ball, swimming, hand-to-hand combat, and the dreaded obstacle course. We, at times, were also pressed into slave labor. Occasionally, a platoon would be marched out into the Carolina woods of red clay and small pine trees where a rock crusher was located and we fed boulders into the machine, which worked like an oversized food processor and broke up the boulders into gravel which was then graded into various sizes by passing over steel grates with ever-increasing hole sizes.

The school was often referred to as ‘Cripple Hill,’ and for an obvious reason. The infirmary was kept busy with injured cadets. Life Magazine visited our campus for an article they were doing, and we were to put on a show for the photographers, demonstrating pushball. The ball is about ten feet in diameter, soft rubber, and inflated. Two teams of approximately thirty members per team tried to push the ball over the others’ goal line. The demonstration got so violent that one cadet had a broken leg, and several others had broken arms or dislocated shoulders. Chapel Hill wasn’t called ‘Cripple Hill’ without reason!”

Marousek explained how he made the baseball team, and what it was like to see his parents, New York Mets fans, in the stands, watching him play in a game with major-league trainees.

“April is baseball season and the Hill was forming a team. Don Kepler, a full lieutenant, was the manager, assisted by Lt. J.G. Buddy Hassett, who played first base for the New York Yankees for a few years. Tryouts would take place at 3:00 P.M. (1500 hours) after classes on the stadium field. A crowd showed up for tryouts. Among the cadets were such Big League stars as Johnny Sain, ‘Ace’ Williams, Buddy Gremp, Johnny Pesky, Ted Williams, Harry Craft, and others. Obviously, these cadets would make the team. Those of us who weren’t Big League stars were sent to another diamond for tryouts. Coaches and V-7 officers were in charge of selecting prospective players. Although I was normally a first baseman in high school and college, I decided to go out at shortstop during batting practice, where I had a better chance of showing what I could do. Fortunately, a few ‘hot ones’ came my way and, after fielding them cleanly, one of the coaches called me in to swing the bat. After hitting a few liners, I was sent over to the other diamond where the ‘big’ guys were working out. Once again I demonstrated my capability and took over first base from Buddy Hassett during infield practice. Coach Kepler seemed to be impressed so I was accepted. I made the team!! There were but two cadets on the team who were not former Big League players. This was my brightest hour in baseball! We played the Naval Academy, Norfolk Navy Yard (Dominick DiMaggio), Duke University, and many other college or Service teams up and down the East Coast. Because we had to travel, generally by Navy bus, we had to uphold the tradition of the Navy by looking our best, so we were all measured for Navy blue uniforms then and there. These were the same uniforms the Annapolis cadets wore. The rest of the cadets didn’t get their “Blues” until graduation day three months later!! I enjoyed those three months immensely, particularly playing ball and meeting so many great guys.

One of the cadets who arrived shortly after me was Cornelius Warmerdam (pictured, U.S. Navy Pre-Flight Archives) the great pole vaulter. When the thirteenth battalion arrived I was glad to see Bob Fournier and Don Ireland. However, since we were in different “batts” and different stages of the training syllabus, we only got to see each other at mealtimes or on weekends.

One of the things none of us will ever forget was the greeting new cadets received from those cadets already ‘established’ at a training site. As the Navy buses brought in the new, wide-eyed recruits, the familiar cry of ‘You’ll be sooorry!’ echoed around the station. This tradition, I soon learned, was carried out at each Base in the entire Training Command.

I don’t believe any cadet can ever forget the discipline and training received at any Pre-Flight School. I must admit making the baseball team did give me certain ‘privileges.’ Sure, the prestige and recognition were nice, even the chance to wear the blues and leave the Station each weekend was great, but, most importantly, Don Kepler didn’t want any of his players hurt so we were excused from the dreaded Obstacle Course in the afternoons and attended baseball practice instead. My fellow cadets kidded me about going through Cripple Hill on a ‘scholarship’!

When our ‘Cloudbuster’ team visited Annapolis to play the Navy cadets there on Sunday, Mom and Dad came down to see me. It was a great thrill for me to play with such distinguished players—undoubtedly the closest I ever got to playing professional baseball, a dream Dad had always had for me. I felt I let him down that day—I went hit less!”

Marousek echoed that sentiment when his grandson interviewed him for a high school project.

“He found my questions difficult and uncomfortable to answer,” said Bermond in an email. “When I commented that I could never do all that, he said, ‘You could and you would, there’s no doubt in my mind. We didn’t want a fight, we just wanted to play ball. But … there’s a job to be done and a war to be won.’”

Marousek wrapped up his accounting of Pre-Flight, offering a bit of advice to the current generation about the things he learned in Chapel Hill.

“Navy Preflight school will always remain in my mind, as it will all other cadets, as one of the greatest experiences of my life. First off you don’t even get to see an airplane, much less climb into one. Oh, sure, you learn all about them in Aerodynamics and see them in Recognition classes, and pretended to fly them in Navigation classes, but actually flight -- no way. However, for mental and physical training it was absolutely tops! (If only civilian high schools and colleges could accomplish that much learning!)

The most important lesson I took away with me when I left Chapel Hill was this: When you are totally physically exhausted and are convinced you can’t go another step, will-power can carry you as far again as you just came. Now, fifty years later, I still believe that lesson.”

♦

Anne R. Keene is a WWII essayist and author of “The Cloudbuster Nine: The Untold Story of Ted Williams and the Baseball Team That Helped Win WWII.” www.annerkeene.com