Walking up to the microphone to share two, original poems on Thursday night at the Torpedo Factory Art Center in Alexandria, Virginia, was an important milestone in the healing process for retired U.S. Navy Cmdr. Bryce Benson.

Nearly three years ago, a 30,000-pound container ship, the Philippine-flagged MV ACX Crystal, had smashed into Benson’s sleeping quarters aboard the Arleigh Burke-class destroyer Fitzgerald where he was commanding officer.

Benson was found clinging to the damaged hull of the ship after sailors forced their way into his room to rescue him. He suffered “severe traumatic brain injury" in a collision that claimed the lives of seven sailors – and has left numerous others, including Benson, with PTSD and other injuries.

Later, Benson faced court-martial for dereliction in the performance of duties through negligence resulting in death and improper hazarding of a vessel. The Navy had initially sought a charge of negligent homicide against him. The charges were dropped, and Benson was allowed to medically retire.

But finding his career over and dealing with worsening post-traumatic stress exacerbated by the Navy’s legal crusade against him, Benson joined a writing program for active-duty service members and veterans sponsored by Community Building Art Works (CBAW).

“There’s no judgement, and there’s acceptance and encouragement along the way," Benson said. “And when you’re looking for healing, those components just go a long way.”

CBAW is the outgrowth of a successful “multi-hospital arts program” implemented at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland, and Fort Belvoir, Virginia, under the tutelage of Seema Reza, chair and executive director.

Reza, a poet, essayist and published author, sought to leverage art and writing to help heal the invisible wounds of war. CBAW hosts monthly and weekly writing workshops at military hospitals, online writing sessions and service member art exhibits and live performances, like Thursday night’s gathering.

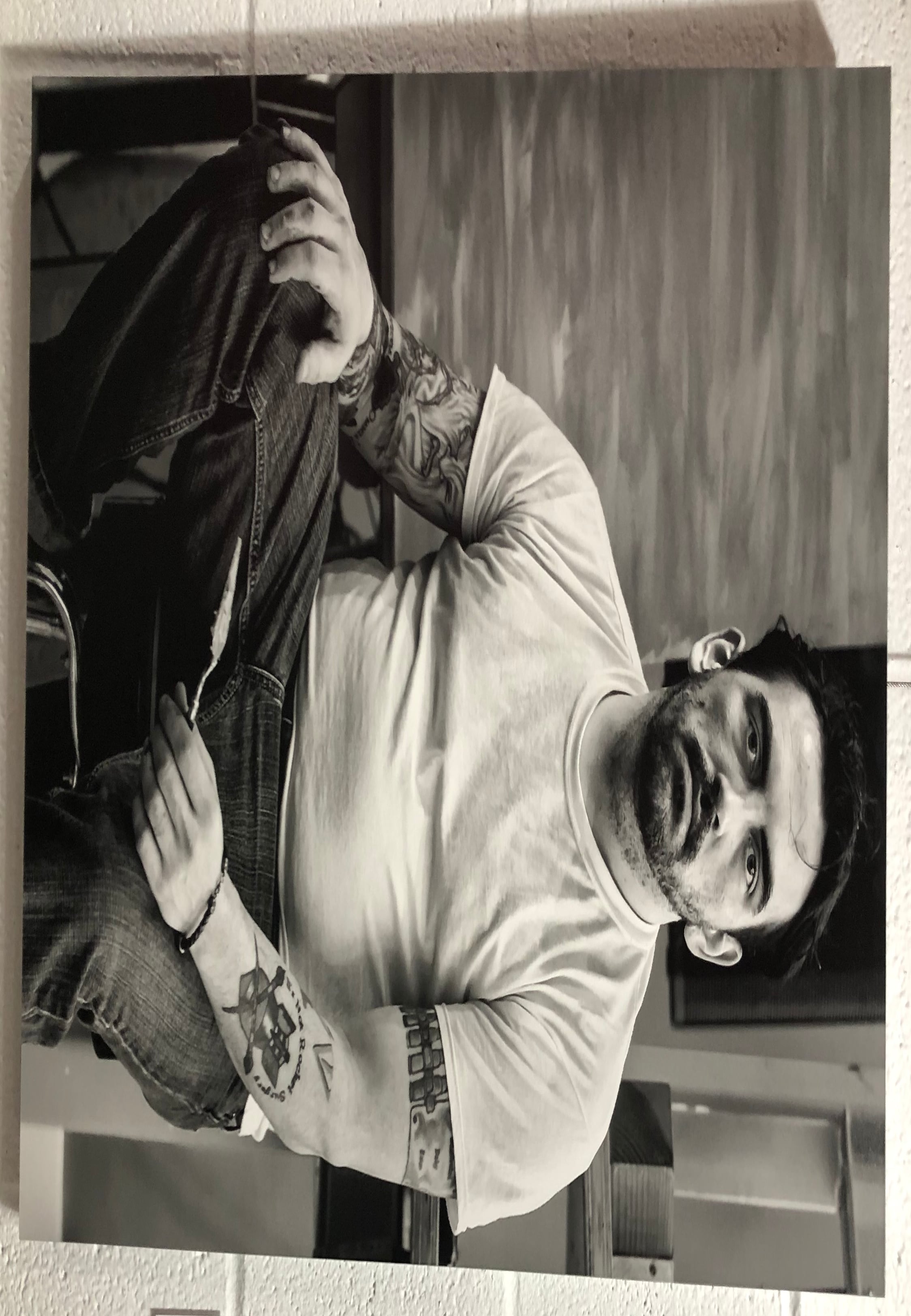

The prose and poetry reading session accompanied the debut of an exhibition titled, “Internal Dialogue: Representing Selves,” a collection of portraits “of and by post-9/11 veterans” on themes of military service, trauma and healing.

“Internal dialogue is about the sort of relationships between parts of ourselves. There’s a version of a veteran or a service member that exists in the American imagination," Reza said. “That’s usually pretty far from the actual experience of service and the varied experience of service.”

“Internal dialogue is about creating space for different selves to exist. The self you were before you joined the service, during your service, and your transition [out]," Reza added.

For Benson, CBAW’s programs provide "a very safe place for active duty and veterans to share very personal things.”

“Once you break down the barriers that there is no spectrum to trauma and recovery, then the healing process can begin. Seema facilitates that through art," Benson added.

“Two ships silently approach. Peace and violence meeting on the high seas while I slept, unaware of the danger. The quiet calm and the gentle sway ended with a 30,000-pound ship puncturing a pitch-black cabin. Steel shattered. Debris became weightless. An aluminum bookshelf rested on my chest.” - Cmdr. (Ret.) Bryce Benson, U.S. Navy

— Cmdr. (Ret.) Bryce Benson, U.S. Navy

Rina Shah, a retired U.S. Army captain and founding board member of CBAW, emphasized the importance of their programming before kicking off the evening as the first presenter.

“People have these preconceived notions of what veterans are and what civilians are. Events like these help keep dialogue open and let people talk about their experience,” Shah said. “I think for veterans who are struggling, for them to see other veterans who have struggled to kind of move past the struggle and be able to have meaningful lives, is important.”

Shah shared a prose reflection on living with grief and accepting circumstances beyond her control.

Other participants included U.S. Army Sgt. 1st Class Stephen Rask, who shared three original poems for the first time – “Abandoned Youth,” “Blue,” and “Leadership.” Zachary Herrick, a retired Army sergeant, shared a narrative called, “Catfish,” which tied memories of his childhood to being wounded in an ambush in Afghanistan in 2011.

“I’m helpless. I let my brothers down. I’m embarrassed I’ve been shot. There’s no rational thinking behind this. It wasn’t my fault. It’s not my fault.” - Sgt. (Ret.) Zachary Herrick, U.S. Army

— Sgt. (Ret.) Zachary Herrick, U.S. Army

Rene Vincit, a retired Fleet Marine Force corpsman, approached the “Internal Dialogue” theme by sharing entries from his personal journal. The entries broached ideas of self-consciousness, interpersonal connections, daily highs and lows, and feelings of fear, anxiety and loss.

Timothy Brown, a retired staff sergeant in the Marine Corps, spoke about his love for photography – and the challenges he faces after his injuries as an explosive ordinance disposal technician.

Feb. 3 is his “Alive Day.” It has been nine years since an improvised explosive device took his legs and right arm. Reza’s program allowed him to capture the experiences of his fellow veterans as they participated in the writing program.

Anne Barlieb, a retired Army major who piloted helicopters in Iraq, said programs like Community Building Art Works create “safe spaces where people can authentically explore” challenging memories and situations.

“I was very reluctant or resistant to doing it,” Barlieb said. “Finding my internal dialogue and getting acquainted with it — not really with judgement or with any kind of critique. Finding out what’s going on in my head, what I was really telling myself.”

Barlieb shared the story of her suicide attempt five years ago and her journey toward healing. She discussed moments of serendipity, reconnecting with her family background and connecting with other veterans.

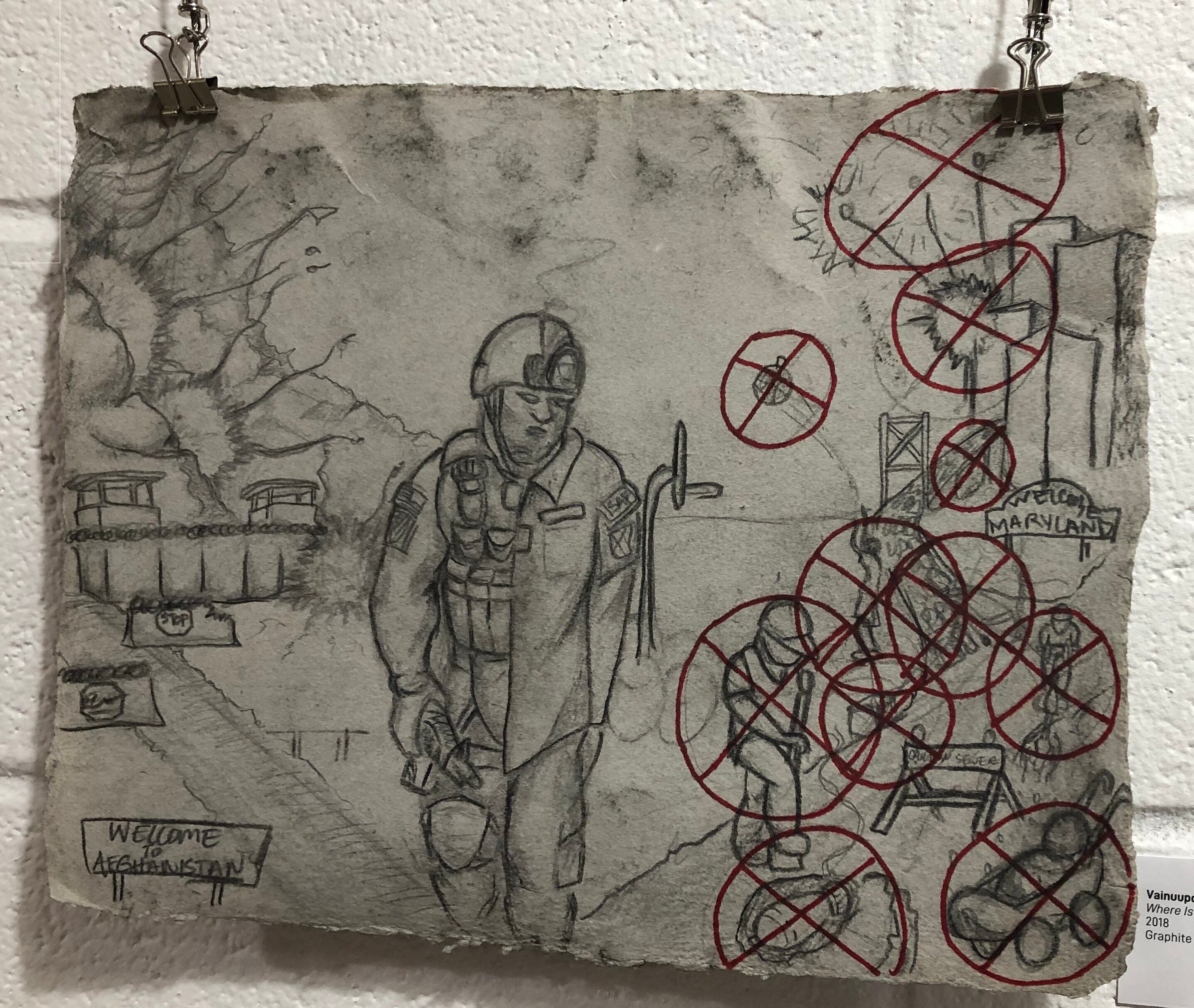

Retired Army Sgt. Vainuupo Avegalio – who goes by “AV” — shared two, original poems for the performance, in addition to having several pieces of artwork featured in the exhibition component.

His first piece, “I Am A Sergeant,” discussed the mindset and emotions of a sergeant leading his soldiers. AV’s second poem, “My Kids,” described his struggle with PTSD, related to an incident where he made a judgement call to fire on a bus suspected of being a vehicle born IED.

The bus had ignored warning shots and had blown through an Afghan National Army checkpoint, closing in on the Americans’ positions. Avegalio later boarded the bus to find 13 deceased kids.

“These are the two kids that I see every night. It’s been 8 years. Every time I go to my house, those two kids are still there. They don’t say anything. They just stand…and yell sometimes. I don’t know how to get rid of them. I do know that I can acknowledge them because all I can do is say sorry every time.” - Sgt. (Ret.) Vainuupo Avegalio, U.S. Army

— Sgt. (Ret.) Vainuupo Avegalio, U.S. Army

For Avegalio, his journey with visual and written storytelling did not begin voluntarily, but he has found healing and a community in the process.

“There’s power in telling the story. Not only is it keeping you from having to shoulder that burden by yourself and holding in all that pain,” he said about Reza’s writing programs. “It’s not easy, but every time you tell your story – getting up and telling it, or poetry, or paintings and photography – that’s a little bit of stress that is alleviated from you.”

“When you have a community, whatever that community is, if that community enables you, empowers you to be a better person, to be stronger every day, to get up and do whatever the things are that you want to do,” Avegalio said. “Be a part of that community.”

In 2018, Avegalio, Barlieb and other veterans with CBAW were featured in the HBO documentary, We Are Not Done Yet. The film highlights the journey from writing poetry and prose to performing the shared project in front of a live audience.

For veterans like Benson, Reza’s writing program has allowed them to find a meaningful outlet for grief, trauma and pain.

“We all came in as a volunteer and figuratively sign that blank check up to and including our lives, and a lot of us came very close to cashing that check,” Benson said. “[Here], there’s an immediate understanding of what the value of our service is. It’s one of those barriers that is broken down.”

“I think the thing that keeps us from saying these things and expressing ourselves is this fear that we won’t be accepted,” Reza said about the live performance. “And when you come to the place where you are willing to say it in front of a group of people, you’ve come to a place where you trust enough in other people.”

It has almost been a year since Community Building Art Works left Defense Department funding, making the nonprofit’s financial footing less certain. But Reza said that the community has stepped up to support these programs, and she continues to look for new veterans to join her online or in-person workshops.

“The importance of creating spaces for active duty service members to tell their truth without censorship, maybe isn’t the best place under federal money,” Reza said. “Maybe it’s the responsibility of the American people and foundations and organizations that are committed to the truth.”

The exhibition, “Internal Dialogue: Representing Selves,” will run through March 15 at the Torpedo Factory Art Center.

Dylan Gresik is a reporting intern for Military Times through Northwestern University's Journalism Residency program.