In the late evening and early morning of Nov. 12-13, 1942, the United States and Japan engaged in one of the most brutal naval battles of World War II.

Minutes into the fight, north of Guadalcanal, a torpedo from Japanese destroyer Amatsukaze ripped into the port side of the American light cruiser Juneau, taking out its steering and guns and killing 19 men in the forward engine room.

The keel buckled and the propellers jammed. During the 10-15 minutes the crew was engaged in battle, sailors vomited and wept; to hide from the barrage, others tried to claw their way into the steel belly of their vessel. The ship listed to port, with its bow low in the water, and the stink of fuel made it difficult to breathe below deck.

The crippled Juneau withdrew from the fighting, later that morning joining a group of five surviving warships from the task force as they crawled toward the comparative safety of the Allied harbor at Espiritu Santo, in the New Hebrides.

Fumes continued to foul the air in the holds; many of the ship’s original complement of 697 sailors — which included five brothers from Waterloo, Iowa — were crowded together topside, blistered from the sun.

At 11:01 a.m., a Japanese submarine tracking the vessels fired another torpedo into the already off-kilter Juneau.

A sudden, furious explosion ripped it apart; underwater blasts followed, likely as its boilers burst. The forward half of Juneau at once disappeared. Then the sea swallowed the stern.

The blasts shot an array of material into the air and fragments of the cruiser struck its sister ships. The turret from a huge antiaircraft gun flew from the vanishing vessel to within 100 yards of another.

Body parts fell from the sky.

The men below deck almost certainly drowned at once. The explosion’s aftereffect might have sucked most of those on deck to the bottom, while the blast blew others to bits.

Many of those pitched clear soon died of their injuries, or of poisoning from the black fuel oil, scalding water, or flying metal. They were burned from the fire of the blowup, covered with thick oil, belching salt water.

The dead, the quickly dying, and assorted human carnage floated in a huge oil slick.

Almost two months later, in early January 1943, the Navy gave fuller details of the eventual American victories at Guadalcanal, but also announced the great cost of the engagements.

Among the losses on Juneau were the five brothers from Iowa, the Sullivans: George, 27; Francis, or “Frank,” 26; Joseph, known as “Red,” 24; Madison, or “Matt,” 23; and Albert, or “Al,” 20.

It was — and remains — the single greatest wartime sacrifice of any American family.

The Navy immediately picked up a thread begun before the brothers’ deaths to weave a story about the Sullivan family — one continued by newspapers, filmmakers, and Midwestern and national leaders. It was American myth-making at its finest, serving to distract a grieving family from its loss, misdirect attention from a series of Navy bungles, and help accustom a nation to the idea of sacrifice for the greater good.

Varied authorities with mass media pull would convince Americans of the boys’ luster as the brothers and their family became cogs in a propaganda machine that would transform them all into heroes — individuals unrecognizable to their Waterloo, Iowa, hometown.

The five Sullivan brothers and their sister Genevieve, or “Gen,” grew up with little parental guidance, according to interviews conducted soon after the disaster and in the years that followed.

Locals repeatedly told investigators that their father, Tom, was a physically abusive alcoholic who went on benders whenever he had a couple days off his job as a freight conductor on the Illinois Central railroad. Their mother, Alleta, was often “blue” and, when she had her “spells,” would take to bed for days at a stretch.

All five boys had left school at age 16 or so, barely completing junior high, and were often out of work — in part a result of the Great Depression. Without jobs, Tom’s underage sons snitched their dad’s moonshine and shadowed him to the downtown backstreets to pick up drink.

In 1937, George and Frank enlisted in the peacetime Navy, serving together for four years; when they returned home in May 1941 they found work with their brothers at the local meatpacking plant.

Through the 1930s, the family lived a stone’s throw north of the black neighborhood. Like most whites, the ethnic working class of Waterloo was not at all friendly to “the colored” and kept its distance.

Not the Sullivans, according to town residents. Neighbors spoke of the boys lurking in the African American slum; there they “stirred the shit,” one of its residents recalled, initiating fights so they could beat up blacks.

This was too much even for white Waterloo, which saw the Sullivan youth as “mischief-makers,” acting out a malicious streak a few blocks south of their home.

By the late 1930s, the brothers were mainstays in an early motorcycle club. The “Harley Club” organized rallies and meetings at a biker bar and sped around Waterloo wearing military-style outfits of Italian Fascist design.

The more genteel folks in Waterloo averted their eyes from the scene, intimidated by a large group of men in soldiers’ outfits. One often-repeated story claimed that the boys filched gasoline to fuel their vehicles, and stole and “refurbished” bikes.

The motorcycle club to which they belonged only underscored a way of life not particularly admirable in the eyes of their fellow Iowans. By 1940 and 1941, the brothers had grown up to be habitués of saloons and dance halls, drinking and brawling.

Then came the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. The dramatic American entry into World War II galvanized the five Sullivans, giving their lives an object and shape they had not previously had. The brothers immediately decided to join the Navy — even the youngest, Al, who had married at 17 and had a 21-month-old son, Jimmy.

“We had 5 buddies killed in Hawaii. Help us,” George wrote to the Department of the Navy in late December, asking that the Sullivans and two friends from their motorcycle club be allowed to serve together, as they “would make a team together that can’t be beat.”

“That’s where we want to go now, Pearl Harbor,” explained Frank to the Des Moines Register.

When the boys passed their physicals at the Des Moines recruiting headquarters in early January, the Register wrote that “five husky Waterloo brothers” who had lost friends at Pearl Harbor were accepted as recruits. A photo of them reenacting their physical exams ran along with the story.

In January 1942, the seven team members — the Sullivans and their Harley Club sidekicks — began their month-long training at Great Lakes Naval Training Center near Chicago.

With their prior Navy experience, George became a gunner’s mate second class and Frank a coxswain; the three younger boys and two friends who enlisted with them were all seaman second class.

The Navy acceded to the Sullivans’ wish that they serve on the same ship; the service may not have encouraged family members to serve together, but it did not discourage the practice and even emphasized how it might keep families—two, three, four siblings—whole.

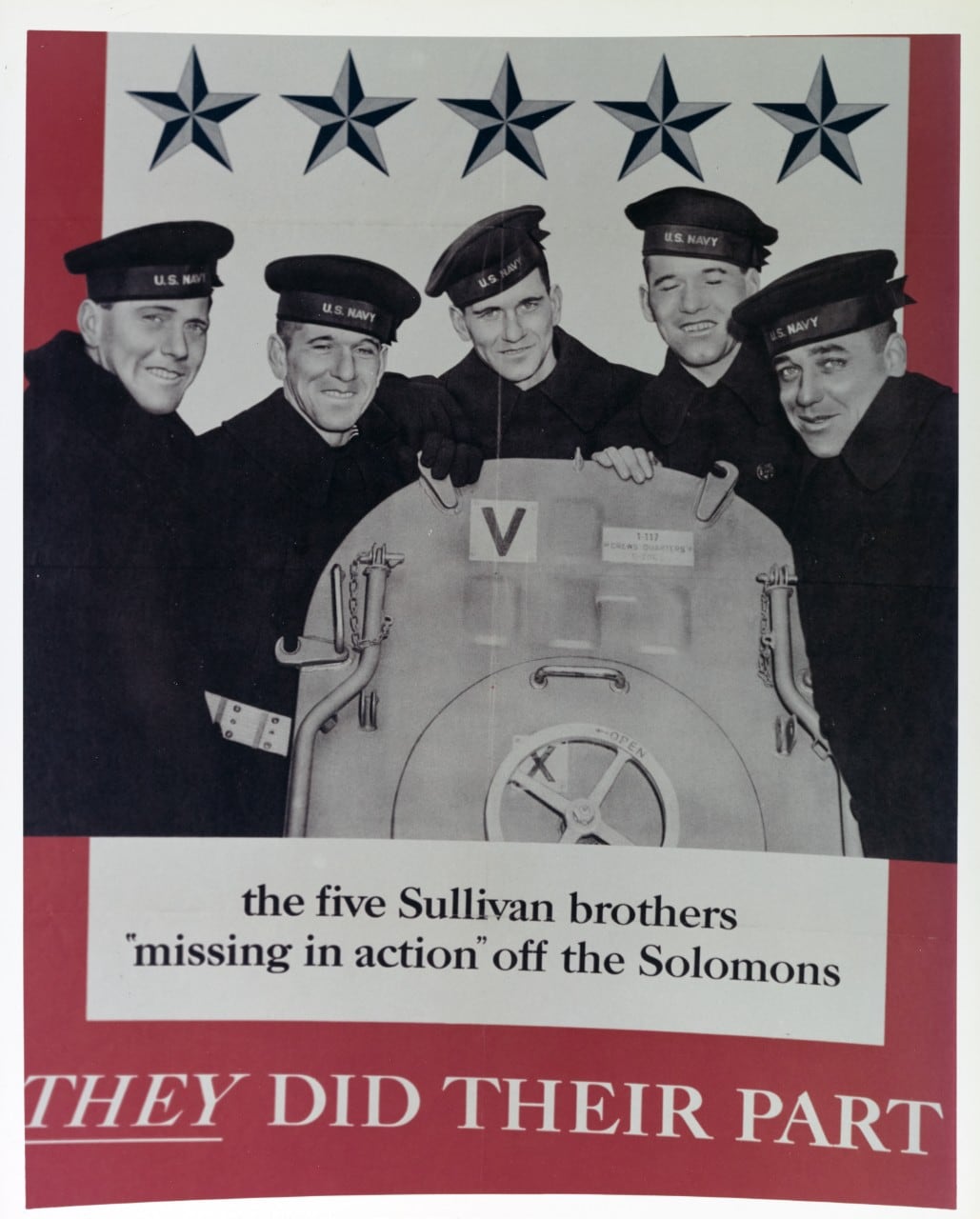

On the day the brothers’ assigned ship, the Juneau, was commissioned— Feb. 14, 1942 — a photographer took a shot of the five smiling Sullivans on board the vessel.

The publicity photo would later become a familiar emblem of American sacrifice.

The family now regularly made the front pages in Waterloo, and the city knew Tom and Alleta’s children as “the Navy’s five Sullivans.”

In March 1942, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox asked Mrs. Sullivan to “sponsor” a ship; she agreed to christen a fleet tug, Tawasa. Ceremonial duties and honors continued to roll in.

The brand-new Juneau spent its first months in service at the periphery of combat against Germany, in the Caribbean and North and South Atlantic before steaming for the southwestern Pacific on Aug. 22, 1942.

With its specialized array of antiaircraft guns, the speedy Atlanta-class light cruiser could protect naval forces from enemy planes. But, with its lightly armored hull and deck, it could be a deathtrap if called upon to attack surface vessels, or if put in their way.

The insubstantial armor also made the light cruiser dangerously vulnerable to torpedoes. After the war, many authorities would testify that these antiaircraft cruisers were high-speed ammunition dumps, easily wiped out by ship-to-ship combat — exactly the sort of battle in which the Juneau was engaged in November 1942.

After the Juneau sank, the crippled group of ships it had trailed hastened on: Japanese subs were still in the area.

“It is certain that all on board perished,” an officer on one of the vessels noted. “Nothing could be seen in the water when the smoke lifted.”

Within a half hour of the sinking, however, an American B-17 bomber flying overhead spotted men in the sea. There were 100 to 200 sailors — many of them badly injured — clinging to debris from the cruiser: mattresses, life jackets, tarpaulins, and three oval rafts, 10 by 5 feet, with decks of wooden slats and attached ropes to accommodate hangers-on.

The B-17 radioed the commander of the flotilla, Capt. Gilbert Hoover of the light cruiser Helena, who continued onward — perhaps misunderstanding; perhaps not wanting to risk more men.

The aircraft circled again to drop supplies, yet for several days the Navy did nothing to assist the sailors. As time went by, their numbers thinned as the remnants of Juneau’s crew succumbed to their injuries, dehydration, or shark attack — a common cause of death.

When South Pacific Area commander Adm. William F. Halsey learned what had happened, he immediately stripped Capt. Hoover of his command.

By the time the survivors were collected — a week after the sinking, on Nov. 19-20 — only 10 men remained.

At least one, maybe two, of the Sullivans survived the initial sinking. Two survivors remembered the death of the eldest Sullivan, George, in particular. He had been on board one of the small life rafts and, after three or four days, was weak and hallucinating.

One night, Gunner’s Mate 2nd Class Allen Heyn recalled, George declared that he was going to take a bath. He removed his uniform and jumped into the water.

A little way from his raft, “a shark came and grabbed him and that was the end of him,” Heyn told a naval interrogator.

“I never seen him again.”

In early 1943, gossip circulating through Waterloo compelled Alleta to send a poignant letter to the Department of the Navy: “I am writing you in regard to a rumor going around that my five sons have been killed in action in November. A friend from here came and told me she got a letter from her son and he heard my five sons were killed.”

She added, “I am to christen the U.S.S. TAWASA Feb. 12th at Portland, Oregon. If anything has happened to my five sons, I will still christen the ship as it was their wish that I do so. I hated to bother you, but it has worried me so that I wanted to know if it was true. So please tell me.”

On Monday morning, Jan. 11, she got her answer.

“I’m afraid I’m bringing you very bad news,” Lt. Cmdr.Truman Jones told Tom and Alleta and Al’s wife, Keena, as they gathered in the family’s living room.

Jones read from a prepared script: “The Navy Department deeply regrets to inform you that your sons Albert, Francis, George, Joseph, and Madison Sullivan are missing in action in the South Pacific.”

The formal announcement made no mention of the foul-ups that punctuated the final act of this drama. As attention across the United States focused on the family at home, the service reframed the colossal loss as an explicable national misfortune and came forward to sympathize and show solidarity.

At the behest of the Navy, President Franklin D. Roosevelt wrote Alleta a personal letter of condolence.

“As Commander in Chief of the Army and the Navy, I want you to know the entire nation shares your sorrow. I offer you the condolence and gratitude of our country. We, who remain to carry on the fight, must maintain the spirit in the knowledge that such sacrifice is not in vain,” he wrote.

Naval authorities encouraged the parents to come to Washington, where First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and Vice President Henry A. Wallace met with the parents.

Some of this may have stirred resentment among Waterloo families who had also suffered losses. In a letter, Alleta later told a friend that the Navy had urged her to disregard the unkind treatment or talk she had complained of receiving back home, telling her — perversely — “it was just jealousy.”

Vice Adm. Clark H. Woodward, at the helm of the Navy’s Industrial Incentive Division, arranged a further project for the grieving parents.

For four months, beginning in February 1943, the Sullivan couple traveled around the United States with a message for the millions in defense industries on the importance of productivity on the home front.

The Navy had other goals as well. If citizens, at the urging of Mom and Pop Sullivan, rededicated themselves to winning the war, the nation might justify the five deaths.

What had happened to the Juneau had also shocked Navy officers, who wanted to mourn with the parents. The service would give Alleta and Tom something to do so that they would not focus on what could not be altered or alleviated.

Finally, the Navy wanted to keep the nation’s attention away from details of the deaths.

The Sullivan parents made scores of stops at defense production plants and war bond rallies.

“We have no regrets that our boys joined the Navy,” Alleta told one audience, in remarks typical of the tour. “I’d want them to do it again; it made men of them. I have a little grandson, Jimmy, who is almost two, and when he gets old enough, I want him to join…. My boys did not die in vain.”

The circuit had to have been grueling — Alleta was reported to have broken down, sobbing, at a stop in San Francisco — but she did see one positive in it: “The trip has kept me from thinking…,” she told a reporter. “It’s bad to think too much.”

Manufacturing and military leaders were appreciative as well. Businessmen praised the Sullivan parents in letters to the Navy, saying that these “plain common Americans” “stirred…workers deeply.”

In an internal memo, Undersecretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal wrote to Navy Secretary Knox that the parents were a “remarkable success” and hoped that the Navy could “use them to the maximum degree.”

On Feb. 22, 1943, Alleta christened Tawasa, as she had agreed to do when the brothers came to the Navy’s attention a year earlier.

Less than two months later, the service gave her a greater honor, when she christened a destroyer, The Sullivans.

Then, in the crowning event, in the spring and summer of that year, the Navy led an effort to make a feature Hollywood film about the brothers.

The Navy’s Woodward and members of his staff persuaded Tom and Alleta to sign a contract that eventually had 20th Century Fox produce “The Sullivans” — quickly re-released as “The Fighting Sullivans.”

The film, which opened in February 1944, told — in the words of its producer — the “wonderful story” of the Sullivans and paid tribute to “an American family and their devotion and loyalty.”

Hollywood showed Tom and Alleta, honest and hard-working, raising their children in a typical American community. Kept in line by strict but caring parents and their church, the children grew up, proper and white-picket-fence, their lives defined by little adventures, minor scrapes, and a growing fraternal bond.

Nonetheless, every happy moment in the movie foreshadowed what all Americans knew was in store.

Critics called it “a distillation of Americanism, of American family life, of American boyhood,” and “deeply touching because of the personal sacrifice it represents.”

The Sullivans were “poor in worldly goods but rich in the stuff that really makes for character.”

The film industry told exhibitors “you can stand in your lobby with your head up while you are playing this one.”

One audience, however, wasn’t buying it: that in Waterloo, Iowa.

The film studio set March 9, 1944, as the date for the local premiere at Waterloo’s 1,800-seat Paramount Theatre.

The city’s newspaper, the Courier, reported the continuing honors showered on Tom and Alleta. The movie house widely advertised the opening; two regional radio stations featured four to eight spots of advertising for the movie per day. Handouts went to grocery stores, and downtown department stores put placards in their windows.

Commemorative festivities supplemented the Waterloo opening. Dignitaries would be present. A 25-member chorus of WAVEs would sing, and an orchestra would perform.

The Courier headlined: “Eager Audiences Wait in Waterloo.” The paper talked about “Iowa’s Own Heroic Family” and “The Name that’s on the Lips of the Nation,” urging: “See the Picture that all Waterloo will be proud to be a part of.”

Promoters spoke about a “capacity” crowd that might generate something like $3,000 for the evening — far above the $1,000 a day similar-sized theaters elsewhere were pulling in.

They warned that patrons might get turned away if they did not put their money down ahead of time.

The day after the premier, Friday, March 10, the news was about who hadn’t shown up. The box office gross for the opening was just $493 — one-sixth of what was expected. In a shattering story, the Courier wrote about how the citizens of Waterloo had resoundingly rejected the Sullivan family.

“From their cold watery graves of the South Pacific,” the story read, the five brothers had come back to their native city. And Waterloo’s thousands disrespected their arrival by sending “fewer than 500 people to welcome them home.”

While the rest of the nation could embrace the family as the symbols that they had become, inside Waterloo the Sullivans remained all-too-real people. An enormous gap existed between what the military, civic leaders, and elected officials wanted and what Waterloo’s residents were willing to give.

The Sullivan Brothers’ story, unlike the brothers themselves, has had a long life span.

In 1952, a stand of trees near the Capitol in Washington, D.C., was planted in their honor.

President Ronald Reagan reflected on “the special burden of grief borne by Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Sullivan of Waterloo, Iowa,” in a 1987 address.

In 1995, Jimmy Sullivan’s daughter, Kelly Sullivan Loughren, christened a new guided-missile destroyer The Sullivans.

And a song, “Sullivan,” by the group Caroline’s Spine, climbed high on the music charts in 1997.

The following year, the film Saving Private Ryan mentioned the deaths in an inspiring scene. Tributes continued into the 21st century.

None of this relieved the unthinkable hardship of the remaining members of the Sullivan family.

“Inconsolable darkness burdened the parents’ last years and reached across generations,” wrote author John R. Satterfield, who interviewed many Sullivan acquaintances, no longer living today, in his 1995 book, We Band of Brothers: The Sullivans in World War II.

As an old man, Jimmy Sullivan said of his grandparents, “I don’t know how they stood it, I really don’t.”

Dr. Bruce Kuklick is Nichols Professor of American History Emeritus. His historical interests are broadly in the political, diplomatic, and intellectual history of the United States; and in the philosophy of history. He has written many books among them one on baseball, To Every Thing A Season. His most recent books are Death in the Congo: Murdering Patrice Lumumba (with Emmanuel Gerard) (2015); and The Fighting Sullivans: How Hollywood and the Military Create Heroes (2016). This story was originally published in the May/June 2017 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here!