From the mountains of Italy to the beaches of Normandy, and from the deserts of North Africa to the ruined German cities, experience the history of the Second World War in Western Europe from 1939-1945 in an entirely different way.

Using unpublished letters and diaries, follow the journeys of some fifty Allied soldiers (American, British, French, Canadian...) as they liberate the continent from Nazi rule, sometimes at the cost of their own lives. Arranged in chronological order and placed in historical context, their stories and letters are illustrated with many personal photographs, war memorabilia and original uniforms.

Having miraculously escaped wartime censorship, these new first-hand testimonies are transcribed as is, whether they come from an elite soldier, a combat medic or a USO dancer. These poignant writings, completed in the mud of the European battlefields, reveal the hopes, doubts and fears of these young people sent to hell, making “Till Victory” first and foremost a book about Peace.

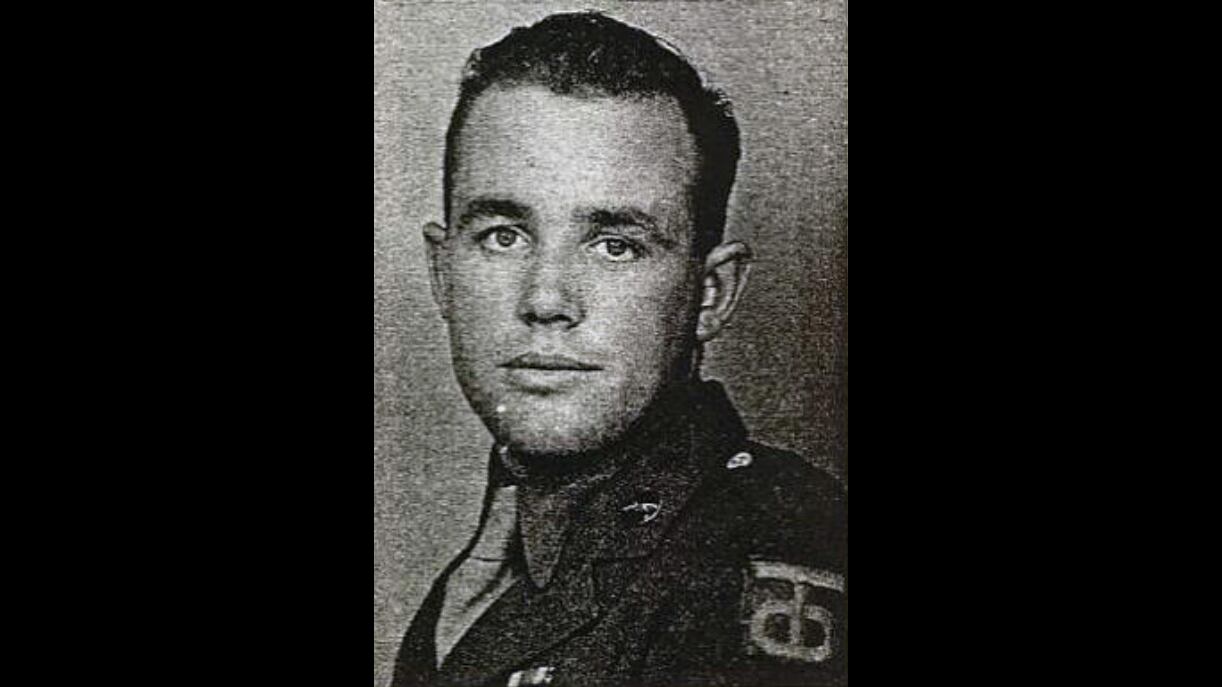

The story of Leo Brown, 359th Infantry Regiment, 90th Infantry Division

FROM TEXAS TO ‘UTAH’

Born in Oklahoma in 1918, Leo H. Brown was a farmer in New Mexico when he joined the US Army on April 1, 1942, in Fort Bliss, Texas. He was naturally assigned to the 90th Infantry Division ‘Texas & Oklahoma’, whose two initials on its patch will give its men the nickname ‘Tough Ombres.’ After a long training period in Texas, Louisiana and California, Leo left for Europe from Fort Dix, New Jersey. He was to land on Utah Beach on June 7, 1944, on D+1, with the reinforcements. But his ship, the Susan B. Anthony, hit a mine offshore that morning and sank in two hours, fortunately without causing any casualties. Leo was picked up by a British ship and tasted English tea for the first time in his life.

When he finally lands on Utah Beach, he’s mixed with men from other units and has no equipment, as everything was lost in the sinking. To Leo’s dismay, the soldiers are given weapons looted from the Germans. Despite a sniper threatening the GIs in the orchard nearby, he takes the risk of venturing alone into the field where crashed American gliders lie. An injured American paratrooper gives him his weapon and ammunition, and Leo finds an M1 helmet, various equipment and precious rations in one of the gliders’ frame. When Leo returns to his company, he’s at last ready to go to war. The division’s mission (attached to the 1st US Army) is to cut across the Merderet River in a westward march, through the Cotentin Peninsula, while other units move up to Cherbourg.

THE HELL OF THE BOCAGE

The Americans discover a terrain as inhospitable as it was unexpected. The Norman bocage consists of an infinite succession of parcels of land, surrounded by centuries-old hedges that are so high, thick and deep-rooted that the US Army will have to develop new additions for its tanks to help create breaches and facilitate the advance of infantrymen. The Germans had dug in and organized solid defenses where snipers, camouflaged Panzers, ambush squads and 88 mm guns provide covering fire for each other. The enemy has set up many traps, sometimes in the shape of a simple wire stretched between two bushes, decapitating Jeep drivers as they pass by. The shell holes in front of the machine gun positions are full of mines, unseen by the terrified GIs who are looking for some cover. The Germans have also prepared small openings at the base of the hedges in order to shoot while taking advantage of the invisibility and protection offered by the terrain. Sometimes, one of them would come out with his hands in the air, pretending to surrender, before throwing himself to the ground at the last moment to let the camouflaged MG42s mow down the GIs who came out of their holes to take a prisoner. American morale falls to a very low point, nerves give way and evacuations for ‘battle fatigue’ become more and more numerous (30,000 psychological losses, for the 1st US Army alone). On a good day, the US Army manages to capture one hedge, while losing a man for every yard of land conquered.

Leo soon watches his first friends fall and by June 9, his company already has only forty-two men left, even though they’ve only been in France for two days. He writes on the 26th: “Here I am in a foxhole in France. I can’t tell you what day I landed but I can tell you that there weren’t very many who landed ahead of us. We have spent nearly all our time on the front lines. I lost my gunner the first day in combat. A sniper got him. I think he will live O.K. [...] He is a really swell boy, but that is the way with war.”

Quinn Buffington, whom Leo lived with every day and night for two years, was shot in the stomach while trying to bring ammunition to G Company. Leo brought him to the aid station just in time and he’ll survive the war. However, he’d spend the next two years in hospital and never really recover. At the aid station, Leo sees rows of dead American soldiers lying on their backs, perfectly aligned. The sight is particularly difficult for him as he’d become very close to many of them during his two years of training.

HILL 122

At the beginning of July, as the Cotentin Peninsula is partially liberated after the fall of Cherbourg, the Allies head south. They are seeking to clear access to Périers and Coutances, but will still have to cross miles of impenetrable and firmly defended hedgerows before reaching these cities. An elite regiment of the 5. Fallschirmjäger-Division (a German airborne division) was deployed to block their route, taking up position on the Mahlman Line, which extends from the west coast south of La-Haye-du-Puits, to the marshy area in the center of the peninsula, in Beau-Coudray. Dominating the line, Hill 122 must be taken by the Allies, whatever the cost. With a panoramic view of the whole Cotentin region, and occupied by an enemy determined to fight to the death, its artillery guns cover all angles. At its foot, the forest of Mont Castre is the 90th Division’s objective.

The attack is launched at 5:30 am on July 3. Leo’s regiment takes the division’s right flank and his battalion advances through a constant barrage of artillery. At noon, German resistance becomes fierce as the battalion crosses a road south of Prétot. The enemy shoots at wounded Americans from the trees, while the artillery fires at will from the heights of Mont Castre. Lying in a field, Leo can hear machine gun bullets mowing the wheat spikes above his head. On its first day, the division has progressed less than a mile on average and Leo has only reached the edge of Sainte-Suzanne, but the Germans pull back a few hundred yards and the village is secured by 9 pm. Despite their heavy losses, the GIs have taken dozens of prisoners, including Russians and Poles, whom the Germans had left behind to buy themselves some time. That day, Leo meets his future commander: “There was a German tank that kept shooting into the big ridge of dirt that we had driven the Germans out of. I don’t know why it was shooting; the ridge was 15 feet thick. Anyway, we got two new second lieutenants. I liked the looks of one of them. They were just standing around as they hadn’t been assigned. One of them just walked out beyond the ridge of dirt, and the tank shot him with the big gun. After that, we only had one new second lieutenant. His name was Lesser. Not long after that, on the 26th of July, the company commander was killed. Lieutenant Lesser took over the company and was made captain and was our commander for the rest of the war. He was a good officer.”

The offensive resumes at 6 am on the next day (July 4), from Sainte-Suzanne towards the eastern edge of the Mont Castre Forest. The GIs manage to reach the road leading to La-Haye-du-Puits, but incessant German counter-attacks and accurate artillery fire make the advance slow and costly. The battalion is forced to withdraw to its former positions at Sainte-Suzanne, where it’ll push back several assaults until late in the afternoon. Leo is given the task of bringing a mortar to the front of the lines to destroy a machine gun nest, even though the enemy is only 100 yards from the GIs, while the minimum range of the gun is four times that distance. Be that as it may, Leo runs back to his platoon, only to find out that they’d already used all their ammunition, despite the fact that they hadn’t received any firing instructions. The commander therefore orders Leo to take a few men with him and go in search of anything the Americans could throw at the Germans.

WOUNDED

With five of his comrades, Leo finds a 12-foot deep depression, at the bottom of which is an American tank facing the German lines. Next to it, a Jeep had just dropped all kinds of ammunition. As Leo approaches the pile, the tank receives the order to move, which always tends to attract the attention of the enemy’s artillery. Thus, as the men hurry to fill their bags with ammunition, they’re shaken by a sudden and deafening explosion above their heads as the German guns fire as expected. One of the soldiers is killed on the spot by a piece of shrapnel to the head, two are seriously wounded and two slightly injured, including Leo.

He receives a fragment the size of a thumb below his right knee, but doesn’t really suffer, even though the piece of shrapnel is white hot (which at least has the merit of stopping the bleeding). Leo manages to walk half a mile to the aid station, where he’s taken care of by a medical officer offering him a dose of morphine. As Leo says, “If it’s all the same to you, I am not hurting that much and I don’t think I need morphine”, the captain replies: “I have a policy: I give everyone a shot because a lot of people are in shock and don’t know they are hurting.” Shortly after, Leo is evacuated by Jeep to a field hospital and then repatriated to England.

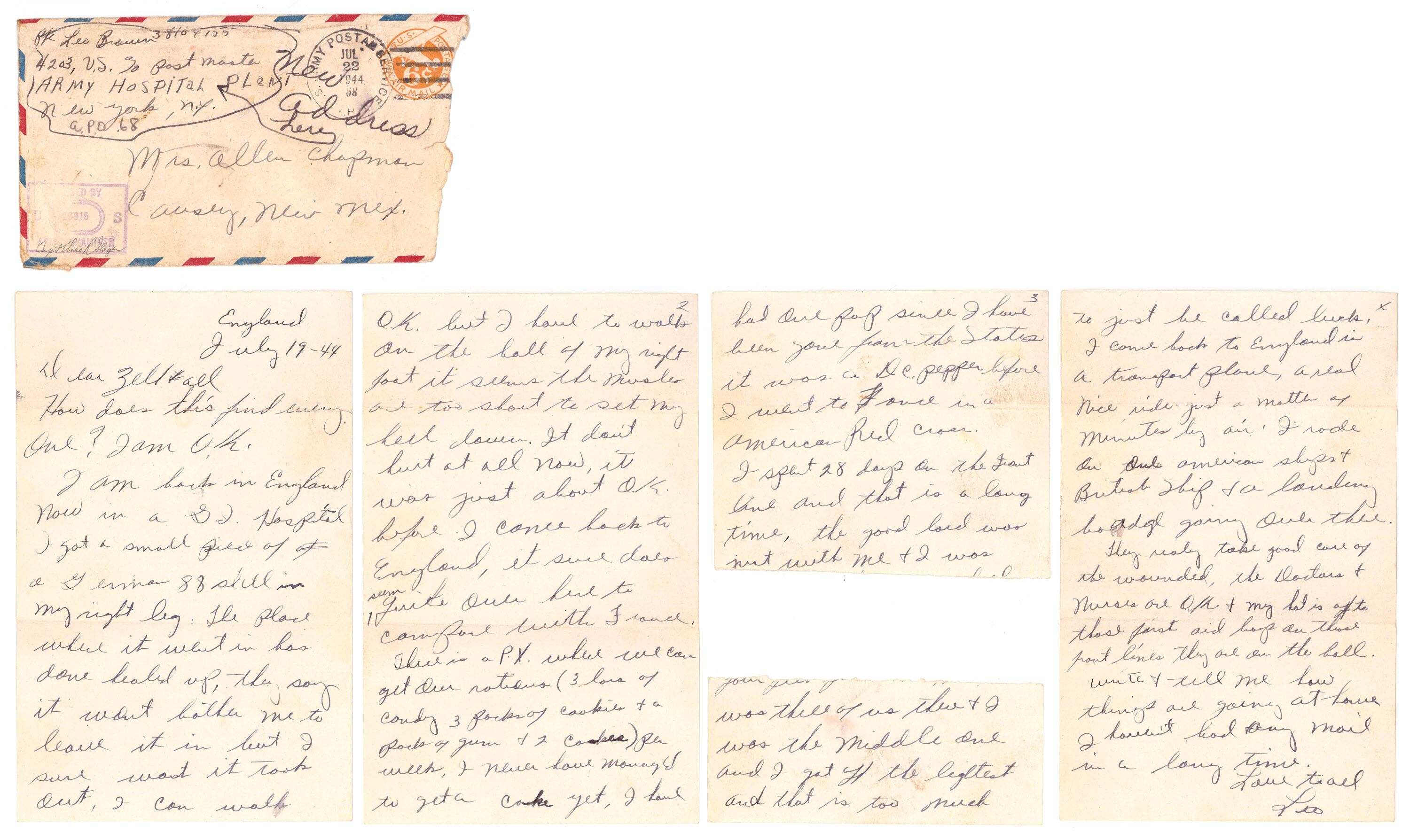

He writes on July 19 from his hospital bed: “I am back in England now in a G.I. hospital. I got a small piece of German 88 shell in my right leg. The place where it went in has healed up. They say it won’t bother me to leave it in, but I sure want it taken out! I can walk O.K. but I have to walk on the ball of my right foot. It seems that muscles are too short to set my heel down. It doesn’t hurt at all now. It was just about O.K. before I came back to England. It sure does seem quiet over here to compare with France. There is a PX where we can get our rations (3 bars of candy, 3 packages of cookies, and a pack of gum + 2 Cokes) per week. I never have money to get a Coke, yet, I have had one pop since I have been gone from the States – it was a Dr. Pepper, just before I went to France, in an American Red Cross. I spent 28 days on the front line and that is a long time. The good Lord was with me and I was [censored segment]. There were three of us there and I was in the middle one and I got off the lightest and that is too much to just be called luck. I came back to England in the transport plane. It was a real nice ride and just a matter of minutes by air. I rode on one American ship, a British ship, and a landing barge going over there. They really take good care of the wounded. The doctors and nurses are O.K. and my hat is off to those first aid boys on the front lines. They are on the ball.”

ONLY THE BEGINNING

The medics will have a lot of work to do in the coming days. The ‘Tough Ombres’ wouldn’t reach Mont Castre until the evening of July 5 and four more days would be needed to dislodge the German paratroopers clinging to its heights. Counter-attacks would multiply and all available men, from engineers to cooks, would be sent into battle to support the American infantry. They’ll only arrive in the village of Plessis-Lastelle, only 3 miles from their starting point, on July 12 at the cost of 5,000 losses. The killed, wounded and missing of the 90th Infantry Division alone would represent more than a quarter of all Allied casualties suffered during the same week, in all theaters of operations in the world combined.

After recovering from his injuries, Leo will return to his unit in November, while the division is on the Saar River, and will participate in the Moselle crossing, fighting for an additional 161 days. He’ll see the end of the war in Czechoslovakia, then return to New Mexico at the end of October 1945 to resume his peaceful farming activities. Leo passed away on August 30, 2006.

“Till Victory” is available for purchase.

French author Clement Horvath insists that he shouldn’t be considered as an historian, but simply a history buff. Nevertheless, he has combined his expertise in images and digital tools with his 15-year collection of letters and relics from the Second World War to conduct his research and carry out his ambitious project from A to Z, in complete independence.

Editor’s note: This is an op-ed and as such, the opinions expressed are those of the author. If you would like to respond, or have an editorial of your own you would like to submit, please contact Military Times managing editor Howard Altman, haltman@militarytimes.com.