Military spouses, like me, living with a depressed or suicidal member face excruciating circumstances. The most difficult thing I have had to do is to support my depressed, sometimes suicidal spouse on a daily basis. It is something that Danny and Faun O’Neel also know all too well. Danny signed up to serve his country on Sept. 11, 2001. He deployed twice to Iraq and served one remote tour to Korea.

“I knew that I had issues, but I did not want the Army to know that I had issues,” Danny told me.

However, before deploying for a third time, military mental health flagged him as someone who should not deploy again, because he suffered with a traumatic brain injury and PTSD. He gave in to pressure not to reenlist, not knowing that he could request a Medical Evaluation Board to determine if he was eligible for medical retirement. As a result, while he physically came home, like many others, he never really came home.

Danny carried heavy burdens, both from his family and from battle. While he lost nine men overseas in his battalion, he has lost 15 men to suicide since returning home.

“If you had not been through what I have been through, then you do not understand” is a mantra that he lived by to hold his pain inside, believing that if he let it out, it would be diminished or invalidated. He paid for therapy in the form of a bartender, turning to alcohol. Many military members struggle with alcoholism or other addictive behaviors to numb pain. He thought that everything he went through was typical, and only after unpacking his story did he realize that his experiences were not. It was not normal to watch your friend be blown up. He finally saw that his responses and behavior did not line up with who he thought he was.

Struggling with his TBI and PTSD, Danny attempted suicide in 2012, by filling all of his medication with the VA and then systematically swallowing 300 pills. He called Faun, telling her what he was doing. Faun called 911. They took Danny to the hospital. He was not held on a mandatory hold, because he told them that it "was an accidental overdose” just so he would be released. It was not an accident.

Faun admitted, “I legitimately did not know what I was doing. I was white knuckling it through most days, acting almost like an EOD [explosive ordnance demolition] technician, walking out in front of him and clearing his path for any triggers that may upset him. Danny’s solution, without the proper tools to deal with what he was dealing with, was always to either leave us, or die by suicide. There was no in between.”

This has been an understandably difficult road for them to walk through, but one that offers me hope that one day there will be healing. Danny and Faun now talk openly about their experiences and about the key role that she, as a spouse, played and still plays in this front line fight.

Danny remarked, “The biggest thing [the military can do] is to support the service member consistently. Around one-quarter of service members deal with mental illness. The military has to take appropriate steps to have help available when those members ask.”

Faun joined in, “No, it’s not enough to simply offer services. You have to shove the help down their throats. None will ask for help; make it to where they do not have a choice. We know they aren’t going to come back from war “OK,” so why are we making it “optional.”

They both agree that with the time, money, and energy the military spends preparing people to deploy, it should spend the same time preparing and training members to come home and reintegrate. My husband received more than two months of pre-deployment training for a six-month deployment, but no training to come back home.

Faun explained that many days, she felt like he was giving up, but she kept fighting, even though discouraged and disheartened. Wives can feel like they are dragging “a 220-pound man through the darkest days, to shoulder all of the burdens of a family day in and day out because your husband, who led men bravely into battle, cannot function in this world some days. Being a combat vet’s wife is isolating because nobody in the civilian world understands, nobody gets it.”

Through persistence, they found people who did care and who did understand, and Danny threw himself into doing the hard, dirty work of getting better.

“I was afraid. I did not want to dig into the box of emotions I’d shoved down, and just cause more chaos. But, once your eyes are opened, it is impossible to go back. You just have to take the first step,” he said.

Danny talked about how we always want our military to be the away team because we do not want war on our doorstep. But one of the problems with being the away team is that sometimes, they do not confront their demons from battle; they don't ask for help. These individuals bring the war to their spouses and children.

“No man I know would invite their wife and child to stand on the front lines of war with them. What they need to realize is that by not addressing the wounds incurred in war, they are putting the ones they love the most on the front lines,” Faun told me.

Struggling military members have very little margin and as an example, can’t tell if a driver cutting him or her off in traffic is actually a threat. Danny has been helped by the “5-minute, 5-year rule.” In triggering and stressful situations, he asks himself if this will matter in 5 minutes or in 5 years. Frequently, it will not matter in 5 minutes, or if it does, it will not matter in 5 years, and that offers perspective in the small things.

Today, Danny is doing better and Faun continues to walk this journey with him. They know that battle buddies are important both on the battlefield and when the service member comes home. Overcoming the wounds of war and serving in a deployment is a grieving process.

Faun also said that equipping spouses is vital because “teaching someone with epilepsy how to help themselves during a seizure is important, absolutely, but you FAIL them and their family if you don’t also teach the family how to help someone during a seizure. The same principal applies to veterans suffering from PTSD. If you teach the veteran in therapy how to help themselves, that’s important. But you also need to teach the family how to help.”

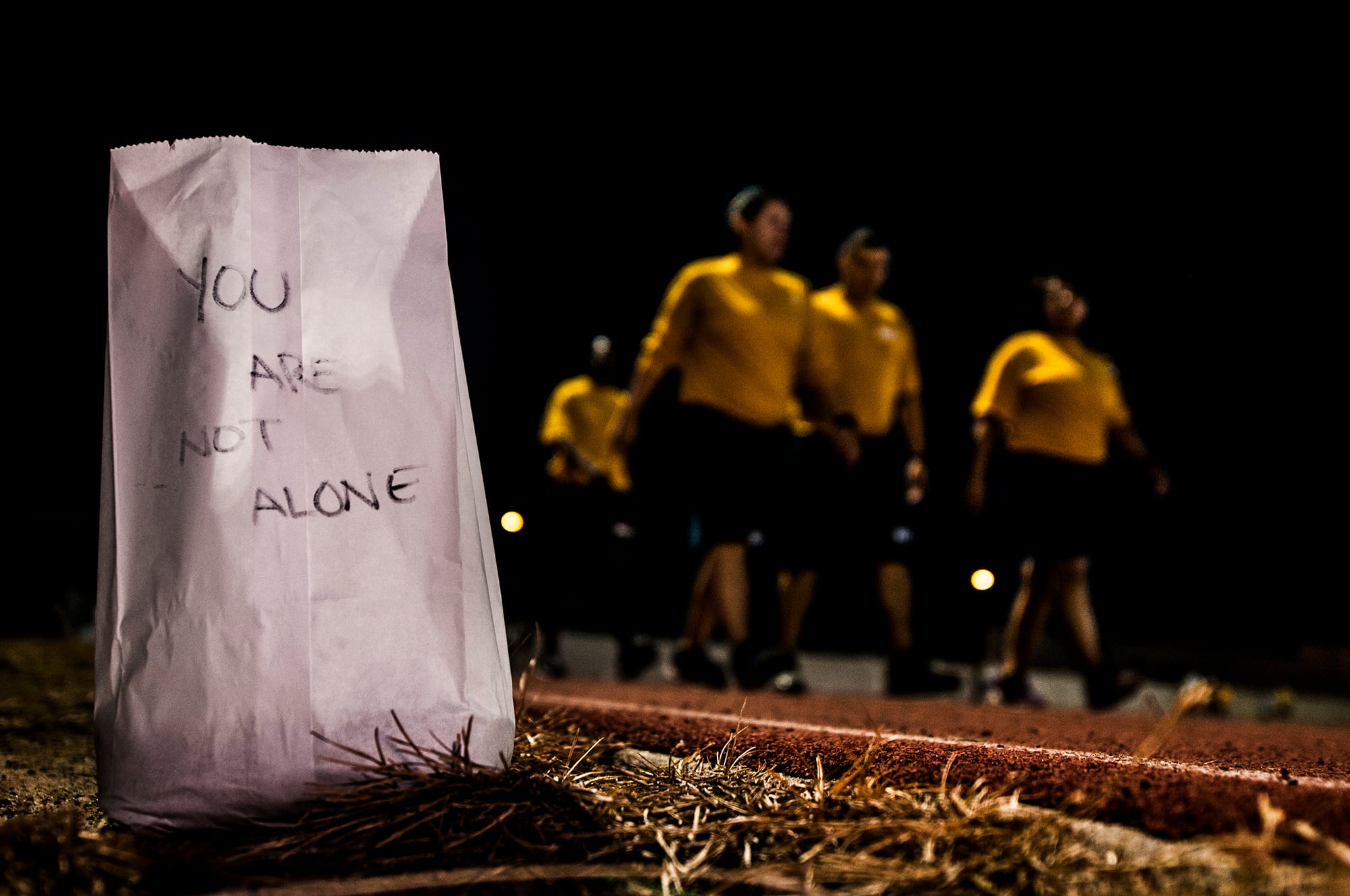

There is hope and there is healing, but “you have to do the dirty work,” Danny summed up. It is vital that the military support spouses and members through greater access to care and ensuring continuity of care with providers. It takes a team to prepare a soldier for deployment and to fight on the battlefields, but it takes a village for that soldier to come home.

If you would like to contact Danny and Faun, please email gwotbaby@gmail.com or go to https://dannyo.us.

If you or someone you know is experiencing suicidal thoughts, please reach out to the Military Crisis Line at 1-800-273-8255, option 1.

Aleha Landry lives in Colorado with her husband and four children, and has spent the last decade as a stay-at-home mom. She has a passion for politics and policy, hates to cook (but cooks much due to aforementioned children), and loves to travel. She holds a bachelor’s of business administration from Colorado Christian University. You may reach her at aleha.landry@gmail.com.

Editor’s note: This is an Op-Ed and as such, the opinions expressed are those of the author. If you would like to respond, or have an editorial of your own you would like to submit, please contact Military Times managing editor Howard Altman, haltman@militarytimes.com.