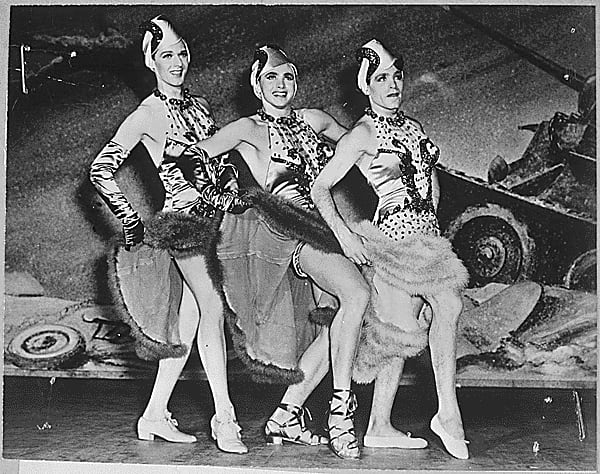

Corsets are tightened, tutus are fluffed, and wigs are adjusted. Men apply heavy rouge and step into glossy high heels before entering stage left. The lights shine down and a line dance accompanied by singing ensues.

While this may sound like it has all the modern day trimmings of a drag show, the year is 1942, and the performers are U.S. soldiers.

The U.S. military has a rather lengthy history when it comes to drag shows, particularly during World War II, when cross dress events were not only sanctioned by the Army, but celebrated as a boon for morale. Because the armed forces were officially segregated by sex until 1948, there was little choice for any service member theater production but to employ men as women.

“From Broadway to Guadalcanal, on the backs of trucks, makeshift platforms, and elegant theater stages, American GIs did put on all-male shows for each other that almost always featured female impersonation routines,” writes author Allan Bérubé.

A now famous production known as “This is the Army” included all manner of soldiers in various costumes. In this production, cross dressing was not only encouraged by the military but actually became a nationwide sensation. Though it was originally a Broadway musical intended to fundraise for the troops, it was eventually turned into a movie that starred an actor named Ronald Reagan, who would one day be president of the United States.

The World War II-era shows, which featured men dressed as women, not only provided a platform for troops to decompress during a time of stressful conflict but furnished a safe space for members of the gay community who were clandestinely serving as well, according to New York University New School professor Joe E. Jeffreys, a drag historian.

While the infamous “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” doctrine barring LGBTQIA+ troops from disclosing their sexual preferences while serving didn’t go into effect until 1994, being anything other than heterosexual was prohibited prior. That was expressly stated in 1982 when a ban on gay service members went into effect, but during World War II, being a member of the LGBTQIA+ community was classified as a mental illness and therefore precluded them from serving.

“The United States military, hoping to screen out mentally ill individuals, asked every potential service member questions on their sexuality,” according to the National WWII Museum. “People who were gay and lesbian were forced to answer questions vaguely, or lie about their sexuality, in order to be allowed to serve; otherwise, they would run the risk of being sent home and branded as ‘sex perverts.’”

That didn’t stop them from signing up to serve. Instead, they simply hid their sexuality and joined anyway. And drag became a refuge. Though they put on costumes, in some ways, these troops were in fact donning their true identities, if only for a brief while.

Jeffreys told Military Times that these shows are largely misunderstood now as a solely LGBTQIA+ activity. That was not the case during World War II and prior.

“By and large, the participants in the soldier shows did seem to be heterosexual,” he told Military Times. “Of course, this was at a time when people really were not declaring in the military one way or the other. But it did offer the LGBTQ+ community kind of a reflection of themselves on stage.”

Drag’s origins, Jeffreys notes, came about through an array of historical theater traditions from cultures around the world. For much of history, women were not permitted to be actors, thereby forcing men to perform in feminine roles.

“Drag really took several pathways,” he said. “One of those is the ancient Greek theater, the Kabuki theaters of Asia, the Elizabethan theatre of Shakespeare, but the drag shows that we think of today are not really coming out of that tradition. Drag as we think of it today really is something that begins with Vaudeville and musical, which is the British form.”

It was, in essence, what we today would call a variety show. And during World War II, lighthearted entertainment was not only desired, it was necessary for morale.

“What fascinates me is that the military was supporting these shows, they were producing these shows, even had handbooks of how to put on one of these shows, how to make costuming out of items that the military had access to [like] parachute material, these type of things,” Jeffreys added. “So, the military was actively involved in this.”

Much of the significant drag history from the Greatest Generation’s era, however, has been overlooked by those seeking to ban the practice.

“Generally overshadowed in histories of the war by coverage of the USO shows and their more famous stars, these shows produced by and for soldiers were as vital to the war effort, incidentally providing gay male GIs with a temporary refuge where they could let their hair down to entertain their fellows,” according to National Park Service records. “Casts of these shows would travel across the globe to perform for GIs and civilians alike. They featured female impersonation and was even performed at the White House for President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.”

Broadway musician Irving Berlin and actor-turned-Staff Sgt. Ezra Stone were the two men behind the wildly successful “This is the Army,” which, according to historical footage, featured everything from ballet-dancing soldiers in tutus to stirring performances of ballads.

“This is a period of time, when generally speaking, a man in a dress was considered de facto funny,” Jeffreys added. “This is this Milton Berle era of drag.”

But shifting perspective in recent years, particularly from GOP lawmakers, have reclassified drag not as a form of theater art but one of both sexual deviance. After a public outcry from conservative lawmakers over drag shows being held on U.S. military installations, the Pentagon banned the practice altogether.

The ban’s announcement, made on the first day of Pride Month, came after on-base events were deemed “inconsistent with regulations regarding the use of resources,” according to a June 1 statement by Pentagon spokeswoman Sabrina Singh.

Although DoD has not financially supported such displays in recent years, performances still had been allowed to take place on base. The ban has already had an impact, meanwhile, with a Pride Month show at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada — featuring a civilian drag queen named Coco Montrese — canceled as a result.

“The Department does not fund drag shows or drag activities,” Cmdr. Nicole Schwegman, Defense Department spokesperson, told Military Times, when asked about that canceled performance.

Rep. Matt Gaetz, R-Fla., who has been outspoken about his negative views on drag shows, tweeted that the cancellation of Pride Month drag shows on military bases was a “HUGE VICTORY.”

“Drag shows should not be taking place on military installations with taxpayer dollars PERIOD!” he added.

In May, Republican senators also penned a note to the Navy, deriding its digital ambassador program for employing Yeoman 2nd Class Joshua Kelley, who performs as a drag queen under the name Harpy Daniels, to aid in recruiting potential sailors through the sea service’s presence on TikTok and Instagram.

Citing a desire to avoid the current controversy, digital ambassador Kelley declined to comment on the ban.

The Defense Department Personnel and Readiness Team, meanwhile, side-stepped the question of why support for drag shows dating back to World War II was recently dialed back. Instead, Schwegman offered that drag is an individual activity troops are allowed to pursue in their free time.

“Service members are diverse and are allowed to have personal outlets,” Schwegman noted. “We are proud to serve alongside any and every young American who takes the oath, that puts their life on the line in defense of our country.”

Sarah Sicard is a Senior Editor with Military Times. She previously served as the Digitial Editor of Military Times and the Army Times Editor. Other work can be found at National Defense Magazine, Task & Purpose, and Defense News.

In Other News