Tom South remembers very little about the day his family got the news.

The 10-year-old boy was half the age of Bill, his older brother. Bill was a soldier. There was a war.

At some point, he doesn’t remember exactly when, a man who was aboard the ship with Bill came to their Bonner Springs, Kansas, home.

Even that is a vague memory. Something about an explosion. And where Bill was, he couldn’t have survived. He couldn’t have faced the icy waters that killed so many after the ship went down. It must have happened quickly.

At least those are the memories that remain 77 years after that fateful day during World War II. And Tom South, a child at the time of his brother’s death, is now 87 years old.

His older brother, Sgt. Myerl “Bill” South, died in the waters of the English Channel on Christmas Eve 1944 along with 762 other American soldiers aboard the SS Leopoldville, a Belgian troopship shuttling more than 2,000 soldiers with the 66th Infantry Division from England to Cherbourg, France.

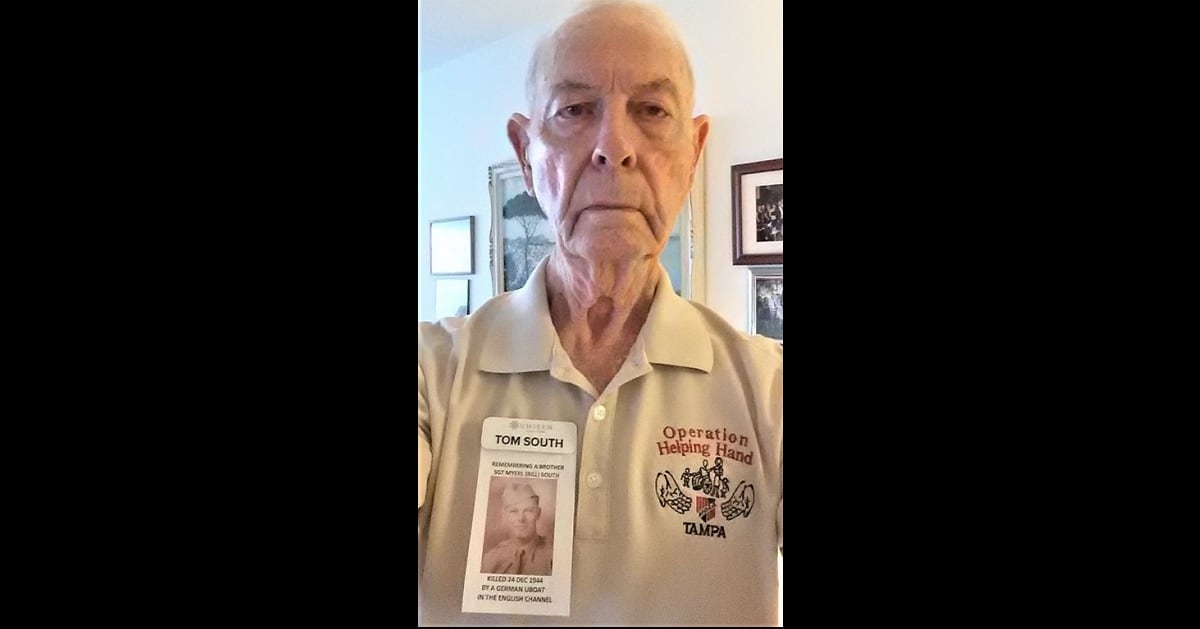

A few years ago, Tom South, himself a retired Army officer, began wearing a kind of homemade badge with his brother’s photograph. Above his slight smile and off-centered garrison cap are the words “Remembering a Brother Sgt. Myerl (Bill) South.” Below the photo, “Killed 24 DEC 1944 By a German U-Boat in the English Channel.”

“That’s all it says, but it at least brings attention to it,” Tom said.

He puts it on for Veterans Day and Memorial Day. It’s a conversation starter, for certain.

The men from the 66th were set to be reinforcements for the Allied push as the Battle of the Bulge raged. They boarded the ship at 9 a.m. Dec. 24, 1944, survivors later told reporters.

One survivor, Pvt. John Pordon of San Francisco, told the Omaha Herald newspaper in 2016 he remembered what they had for to eat, an “awful” Christmas dinner of greenish stew over rice while the ship bounced over channel waves. The combination caused the green soldiers to turn green with seasickness mid-voyage.

“We were all griping about what a lousy way it was to spend Christmas,” Pordon told the Herald. “Little did we know.”

A sudden shaking caught everyone’s attention.

“It felt like an earthquake,” Pordon said. “We knew something had happened. We thought we had hit a mine.”

The ship was about five miles from its destination when a German submarine, U-486, found her exposed and fired a torpedo, sending her to the seafloor. Historians estimate that more than 500 of those who perished went down with the ship. More than 200 others died of injuries or hypothermia awaiting a delayed rescue.

In the rapid ship boarding for the crossing, many of the soldiers hadn’t gotten training on the lifeboats or how to properly use a life vest, Pordon said. He and his company had gone through the drills, however, and that likely saved his life.

His group went to their lifeboat station and waited. And waited.

No one guided the soldiers on what to do next.

“By now we all assumed the ship was sinking,” Pordon told the Herald.

A combination of errors contributed to their predicament: mismatched French, English and American communications systems, arguably lax radio monitoring due to Christmas Eve festivities.

Then a British destroyer escort, the HMS Brilliant, pulled alongside the Leopoldville and its crew shouted at the soldiers to jump aboard. But the destroyer was a lot lower, 40 feet or more depending on the rise and fall of the waves, and the bobbing ships made it hard to time the jump. Pordon saw some of his fellow soldiers try and fail — and get crushed between the two hulls. He stayed on the Leopoldville.

Once the Brilliant was full, it pulled away and reached the Cherbourg port soon after, which was when authorities learned what had happened.

It took another two hours for a small group of rescue boats to arrive on the scene. Many of the soldiers had already drowned or frozen to death.

Those who survived pushed on to join their comrades, who’d made it across unscathed in other ships only to face some of the heaviest fighting of the war in the remaining weeks of the Battle of the Bulge.

Tom South and his family weren’t alone in their search for answers. Despite the tragedy happening in late December, many weren’t told of the sinking until February. Newspaper accounts show some didn’t receive official death notices until April.

U.S. military officials told soldiers not to talk about what happened, Pordon said. The War Department didn’t want the public to know that the Germans had scored such a devastating hit on U.S. troops, fearful it would sap morale or provide information on troop movements to the German military.

Many families simply received a death notice with no further information on how their loved one had died.

Of the 763 who perished, 493 bodies were never recovered. A memorial to those lost in the sinking was dedicated at Fort Benning, Georgia, home of the 66th Infantry, in 1998.

In the South family, they never discussed it.

“It was just a bad memory,” Tom said. All he has of his brother is his service photograph and photo of him with Bill and another older brother. Tom’s just a boy, they are in suits and ties.

Tom grew up and later spent time in the Navy as a ship serviceman and the Air Force before finishing the majority of his military career in the Army, retiring as a chief warrant officer in the Criminal Investigation Division.

He belongs to the Military Officers Association of America, or MOAA. The group, especially his local chapter in Tampa, Florida, does work honoring the Missing in Action.

“What better way to reconnect, to honor those regardless of when they lost their lives or what service they were in?” he said. “The one thing I could do was recognize my brother’s loss.”

I live in an independent living facility here in Tampa. Each resident is given a nametag for socialization.

“I thought my brother Bill deserved to be recognized,” Tom said. “I am just an old man doing a long-overdue salute.”

So, each Memorial Day and Veterans Day he wears his badge. And people ask about Bill. And the little boy who looked up to his big soldier brother gets to talk about the man he never got to know.

Editor’s note: Tom South and his family are of no known relation to Army Times reporter Todd South, author of this article.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.