The fifth installment in an illustrated series dedicated to soldiers whose actions earned them the nation’s highest award for military valor is now available online.

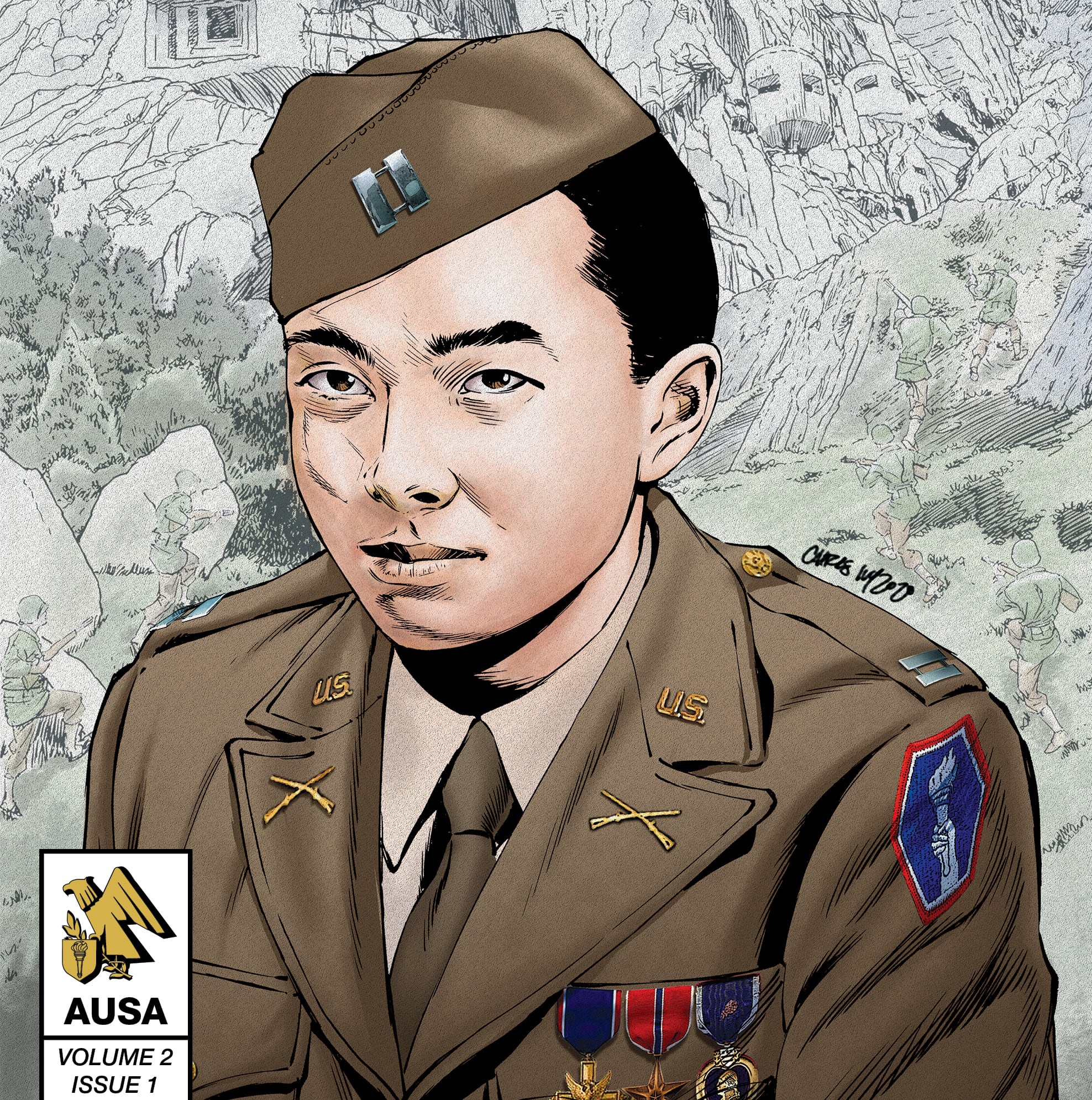

The newest issue of “Medal of Honor,” a graphic series produced by the Association of the U.S. Army, spotlights the World War II heroics of Daniel Inouye through story-telling and visuals constructed by some of the comic industry’s top writers and artists.

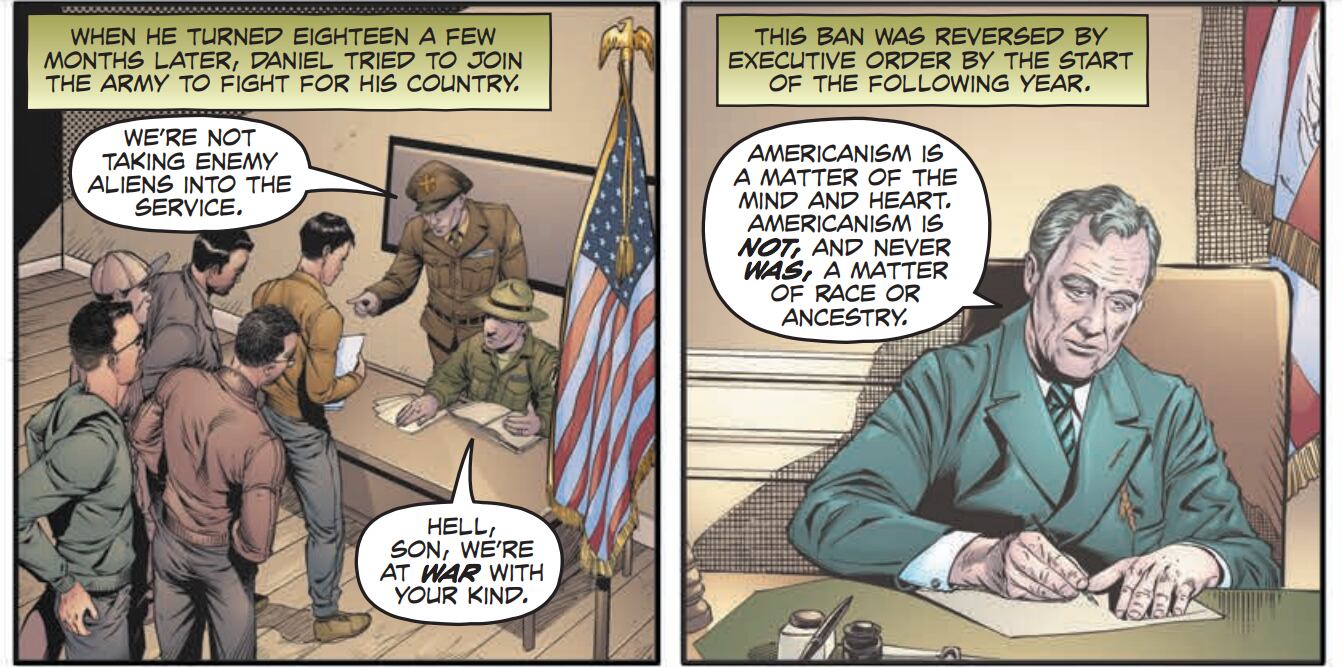

The native Hawaiian’s road to history began when he witnessed the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor first-hand. Despite his eagerness to fight for his country, Inouye was prevented from enlisting until 1943, when the Army ended its ban on Japanese-Americans.

After basic training, Inouye was assigned to the segregated 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which would go on to become one of the most decorated units in the war.

By 1944 he was serving as a platoon sergeant in France when the men of the 442nd were tasked with rescuing 36th Infantry Division soldiers who had found themselves surrounded by Nazi troops. Intense fighting ensued, and the all-Nisei unit managed to break through German lines to rescue more than 200 men from the 36th.

During the assault, an enemy round struck Inouye directly in the chest. The two silver dollars in his blouse pocket that miraculously stopped the projectile would become good luck charms he would carry for much of the war.

For his role in the attack, Inouye earned a rare battlefield commission to second lieutenant. Still, the mission came at a steep cost — more than 800 casualties were inflicted on Inouye’s regiment. Multiple companies from the 442nd went in with nearly 200 men only to see fewer than 20 walk off the battlefield unscathed. In fact, the 100th Infantry Battalion would suffer so many losses throughout the war that they would be dubbed the “Purple Heart Battalion.”

In the waning weeks of World War II, the newly-commissioned 2nd Lt. Inouye was charged to lead an assault on Nazi defenses along Germany’s “Gothic Line” in northwestern Italy.

Near the village of San Terenzo, Inouye and his men confronted three enemy machine gun teams on a ridge line at close range.

As he raised up to move toward the first bunker, Inouye was shot in the stomach. Ignoring his wounds, he continued forward to destroy the enemy team using a combination of his Thompson machine gun and hand grenades. He then turned his attention to the second bunker, directing his men before collapsing due to blood loss.

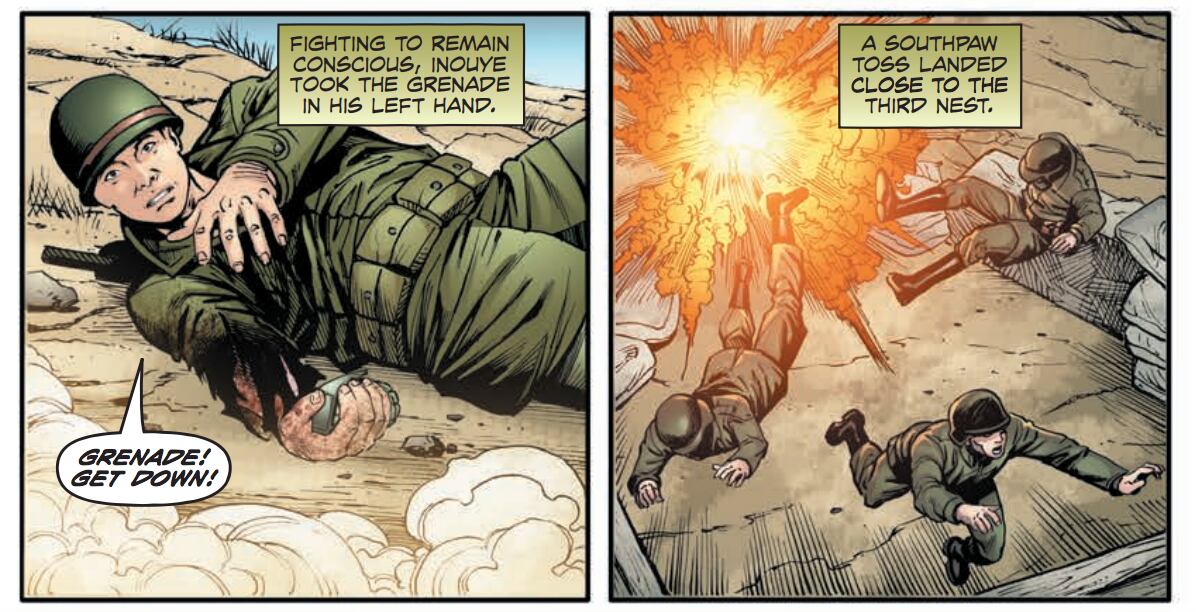

The wounded Inouye moved in a prone position to within 10 yards of the third machine gun nest. Just as he propped himself up to throw a grenade at the remaining gun crew, he was hit in the elbow of his throwing arm by a 30mm rifle grenade that failed to detonate. The force of the round’s impact, however, left Inouye’s arm hanging by just tendons and one section of skin.

Inouye’s lifeless hand still clung to the active grenade he was readying to throw, the tight-grip of his severed fist the result of nerve damage that tightly enveloped his hand around the explosive.

The grievously wounded lieutenant screamed at his approaching men to keep back out of concern his right hand would relinquish its grip and drop the grenade. As the enemy gunner reloaded, Inouye hastily grabbed the grenade with his left arm and lobbed it into the bunker to finish the enemy off.

He then picked up his Thompson machine gun and continued the assault up the ridge, killing at least one more enemy fighter before yet another enemy round fractured his right leg and sent him to the ground.

Inouye regained consciousness just momentarily to see he had been encircled by his concerned men. Without hesitation, he ordered them to continue the assault.

“Nobody called off the war!” he yelled.

By the time Lt. Inouye was moved into surgery at a field hospital, he had been given so much morphine that surgeons had to amputate the shredded remains of his arm without full use of anesthesia out of fear that any additional medication could stop his heart.

Inouye would spend nearly two years recovering in military hospitals before being discharged as a captain in 1947.

After the war, he would continue to make history as the first Japanese-American to serve in both the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate.

It wasn’t until 2000 that Inouye’s battlefield heroism would be fully recognized, when he was presented the Medal of Honor by then-President Bill Clinton.

Inouye’s heroics and history-making endeavors made him an easy selection for the AUSA team’s fifth installment.

“One of the things I was really impressed with is the level of work that the creative team has put into it,” said Joseph Craig, director of AUSA’s book program.

“The scripts and the artists — these are all people from the world of professional comic book publishing. These guys know comics, they know military comics in particular, and the job is just really top notch.”

The collaborative team included script-writing by Chuck Dixon (Marvel’s “Punisher"), drawings by Christopher Ivy (“Avengers,” “Flash,” “G.I. Joe”), color work by Peter Pantazis (“Justice League,” “Superman,” “Wolverine”) and lettering by Troy Peteri (“Spiderman,” “Iron Man,” “X-Men”).

Upcoming editions of the series, meanwhile, will feature World War I Harlem Hellfighter Sgt. Henry Johnson, Civil War surgeon Dr. Mary Walker, and Holocaust survivor and Korean War veteran Cpl. Tibor Rubin.

Read the full Daniel Inouye graphic novel here.

J.D. Simkins is the executive editor of Military Times and Defense News, and a Marine Corps veteran of the Iraq War.

Tags:

Daniel InouyeDaniel Inouye HawaiiDaniel Inouye Medal of Honor442nd World War IIPurple Heart BattalionMedal of Honor graphic novelsMedal of Honor WWIIDaniel Inouye world war iiIn Other News