More incidents, less reporting, plummeting confidence in the system to get justice ― those are the takeaways from the Defense Department’s most recent annual sexual assault prevention and response report, released Thursday.

For years, officials have couched increases in sexual assault reports by claiming that survivors are becoming more comfortable with reporting, but for 2021, that math doesn’t bear out.

A survey measuring prevalence of sexual assault, including whether survivors filed reports, lines up neatly with official report counts, showing that not only is unwanted sexual contact rising, but fewer people are opting to report it, and fewer perpetrators are being legally punished.

So this year, officials aren’t couching it anymore: it’s not good. The report estimates that more than 8% of female service members experienced unwanted sexual contact in 2021, the highest rate since the department began counting in 2004. For men, it was the second-highest figure, at 1.5%.

“And what I want to emphasize is, these numbers are extremely disappointing,” Beth Foster, DoD’s director of force resiliency, told Military Times on Wednesday. “They’re tragic, they’re frustrating, but I do believe that we can change this trajectory and I believe that the department has a plan in place to do so.”

There is a bit of nuance in the prevalence estimates since they began in 2006, as they’re based on a department-wide survey. Sixteen years ago, there was one question covering sexual assault. In 2014, that became a series of very specific questions meant to catch multiple types of unwanted contact.

RELATED

For 2021, those questions were scaled back somewhat, under guidance that the numerous graphic questions in the list could be putting people off from answering them.

As they have in the past, the extrapolated estimates show that women in the Marine Corps faced the most unwanted sexual contact incidents ― 13.4%, up from 10.7% in 2018 ― and men in the Navy were the most affected ― 2.1%, up from 1% in 2018.

Overall, the department counted 7,260 sexual assault reports in calendar year 2021, out of an estimated 35,900 incidents, for a 20% reporting rate.

That figure has fallen significantly since the last survey in 2018, when the reporting rate was pegged at 30%. The past two surveys mark the first times the reporting rate has dropped since 2012, when it was 11%.

Not surprisingly, confidence in the military’s sexual assault response system has plummeted as well. In 2021, 63% of male troops were confident that their chain of command would “treat them with dignity and respect” after reporting an assault, down from 82% in 2018.

For women, their confidence dropped from 66% to 39% during the same time period.

Prosecutions are also down. In 2013, the services started court-martial proceedings in 71% of the 1,187 cases that ended in discipline, the highest number recorded. Since then, the numbers have fallen steadily, including a drop from 49% in 2018 to 42% in 2021, with 1,974 cases.

At the same time, the number of perpetrators given nonjudicial punishment, or administrative punishment including involuntary separation, has creeped up. In 2013, 12% of cases resulted in administrative action. In 2021 it was 27%. And nonjudicial punishments are up to 31% from 18% in 2013.

Some of that may reflect survivors’ wishes, according to the deputy director of DoD’s Sexual Assault and Prevention Office.

Anecdotally, Nate Galbreath said, that reflects survivors becoming more comfortable with disciplinary options, more often choosing not to participate in a court-martial process, in favor of nonjudicial or administrative punishments for their assailants.

“In other words, people come in and they’re assigned their special victim counsel, and they’re given the full spectrum of what you can do. You can go to court-martial, you can do this, you can do that,” he said. “And by and large, victims have chosen to participate in disciplinary actions where they don’t have to testify. And I don’t have to tell you, nobody likes to go out in front of a court-martial, public forum, and have their judgment or their morals questioned, right?”

Galbreath added that this has been the case with special victims counsel he’s spoken to, but couldn’t say whether survivors might also be shying away from trial because of pressure from their peers or their chain of command.

So what now?

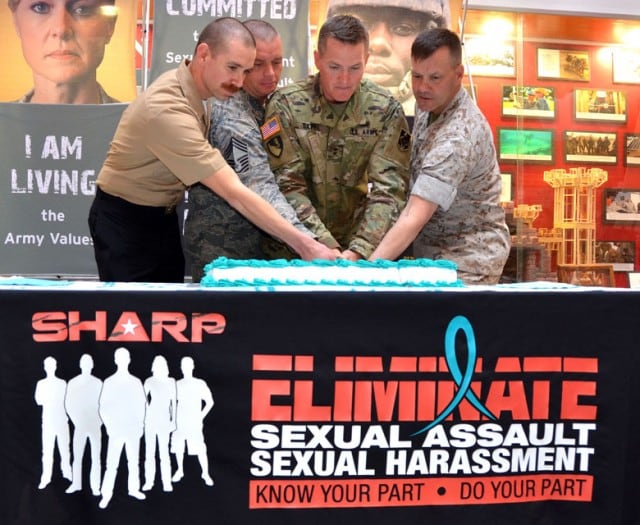

It’s been 17 years since the Pentagon was first ordered to set up its SAPR office, and in that time, resources have tended to be focused on response, in the form of resources for survivors.

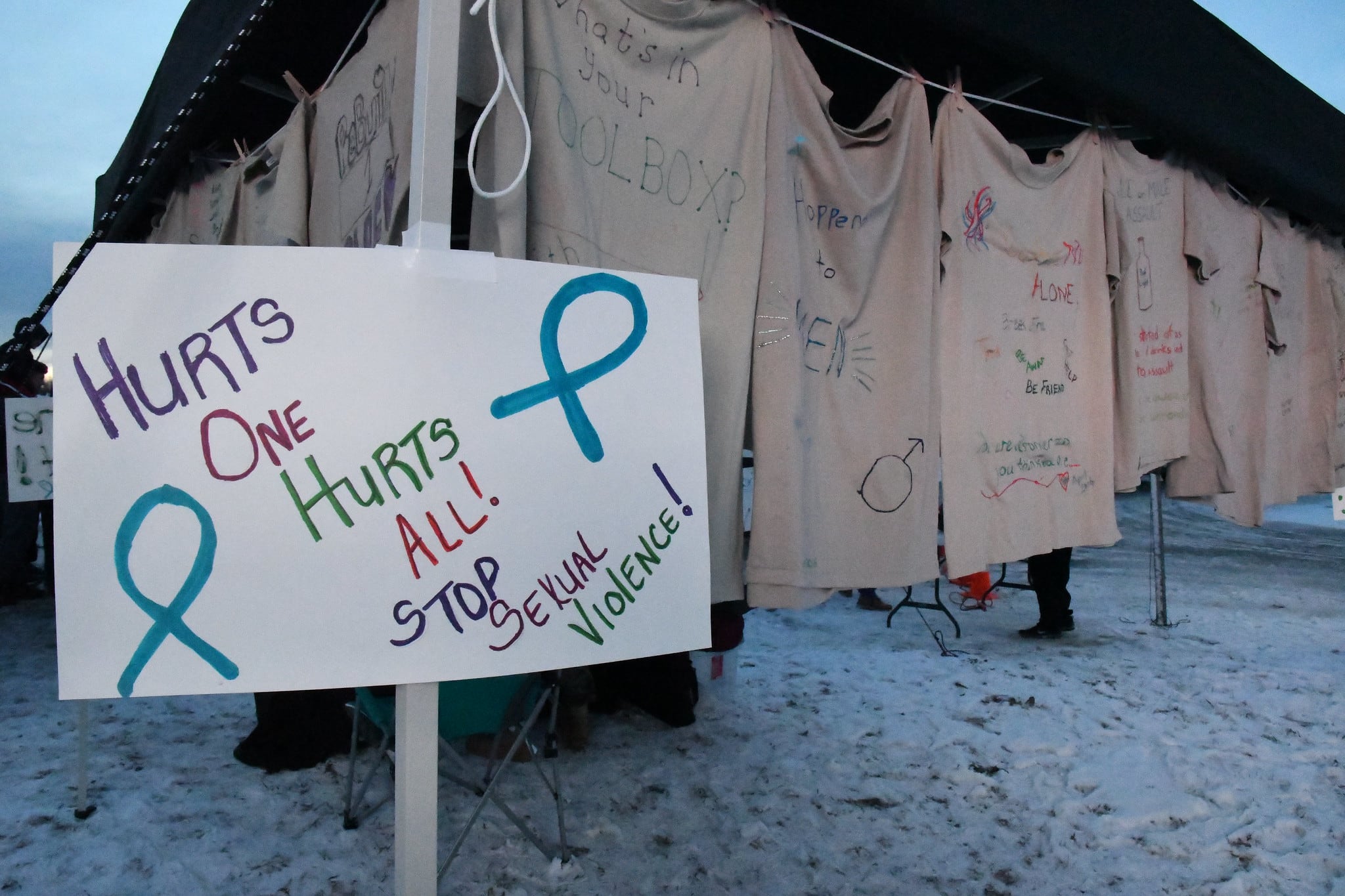

The services, in the past few years, have begun to shift their attention toward prevention, as more than a decade of PowerPoint slides and “don’t rape” lectures haven’t sunken in.

“This is really tough, and we’re going to talk through that,” Foster, the force resiliency director, said. “But we’ve got the way forward. We just need to double down on our efforts to get after this.”

RELATED

Much of that will include implementing more than 80 recommendations from an independent commission that convened in 2021. While several points cover training and education, there is little detail on what new modalities could make the difference.

There are, however, dozens of initiatives that would strengthen the response side, and perhaps not only give troops confidence that the system will work for them, but whose outcomes might discourage perpetrators.

Those include automatic involuntary discharges for substantiated sexual harassment, independent investigators and prosecutors for sexual assault cases, and professional victim advocates.

Another effort, being undertaken in different ways by the services, is more thorough evaluations of commanders and leaders designed to catch poor judgment or lack of action on sexual assault before they are promoted to higher positions, because research shows that toxic command climates are a breeding ground for harassment and assault.

The review commission also recommended publicizing courts-martial results for sexual assault or harassment, to show both survivors and perpetrators that the chain of command will be transparent.

“And so that is one of the things that each of the judge advocate offices have been tasked to do,” Galbreath said. “And so that information will be available. Whether someone looks or not is another issue, but it will be available.”

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.