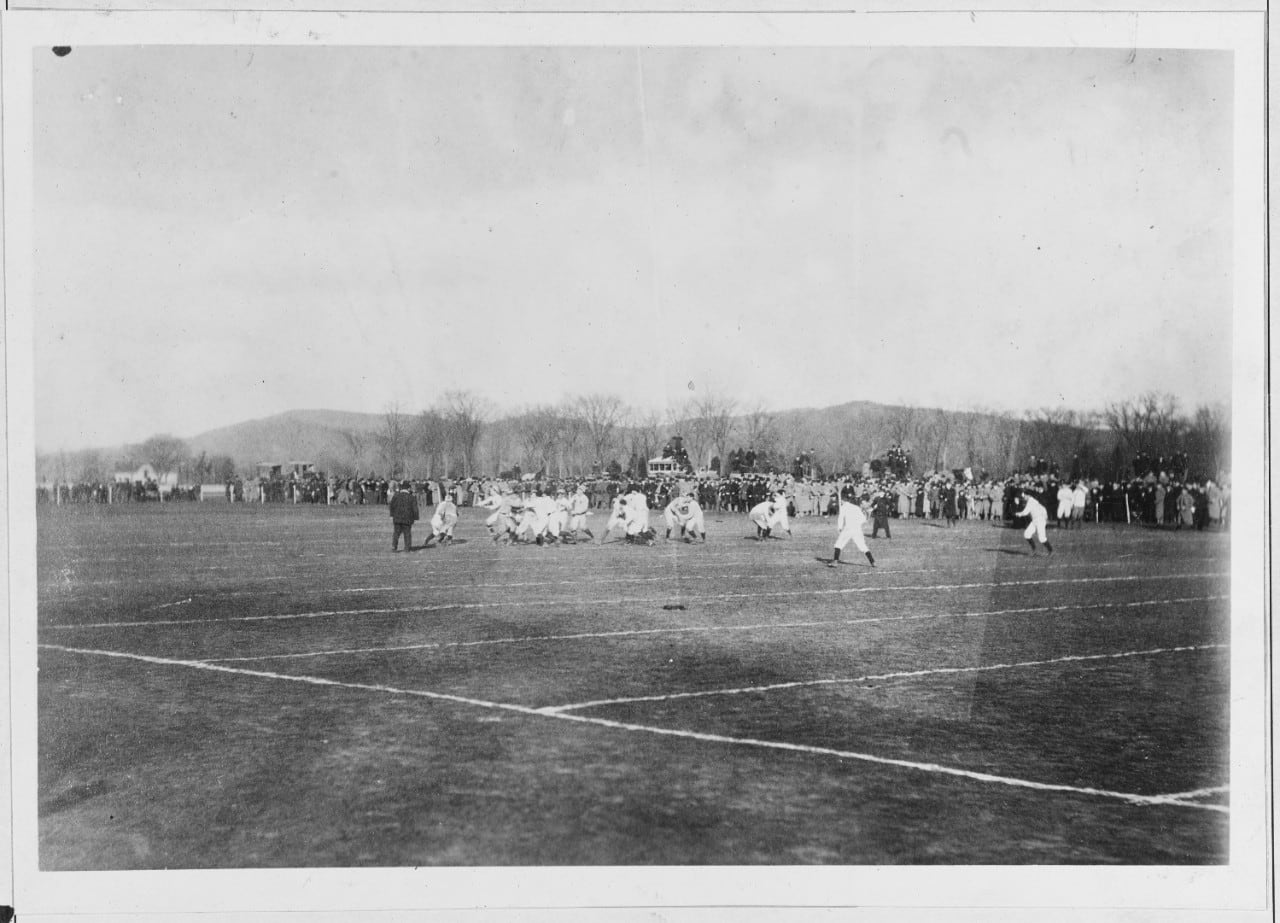

METLIFE STADIUM, EAST RUTHERFORD, NEW JERSEY – Since the Army Navy Game was first played in 1890 the traditions at both of the nation’s oldest military service academies have grown in number and resonance for cadets and midshipmen across time.

Just a sampling includes the marching on of the Corps of Cadets and Brigade of Midshipmen at the start of the game, to pregame bonfires replete with purpose-built wooden ships turned to ash by U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York to the “Ball Run” in which groups from a selected unit at each academy run a football from their campus to the site of the game.

There are also a host of pranks, hijinks and well-meaning jabs both for current students and the far-flung graduates both in and out of uniform.

Army Times and Navy Times spoke with a range of notable academy graduates servicemembers and otherwise with a connection to those institutions and asked them about their favorite traditions and memories while at the schools and since they left.

A long wait

Retired Brig. Gen. Pete Dawkins played for West Point from 1956 to 1958, winning the Heisman Trophy his final season, and beating Navy 22-6.

Dawkins was drafted by the Baltimore Colts but had accepted a Rhodes Scholarship and also owed the Army some time in uniform. He deferred the football draft and instead spent 24 years as an Army officer, doing two tours in Vietnam and one in Korea.

The one-star’s first favorite memory was how he ended up attending USMA at all. The

A star football player at Cranbrook School in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, the young Dawkins had a hard-driving Marine veteran for his coach. The coach told him he should think about going to West Point. The teenager kind of shrugged it off, until coach showed up at his house one day, told his mother to pack the boy a bag that he was taking him to West Point to meet the head football coach, Earl Blaik, who headed the Black Knights from 1941 to 1958.

After a more than 10 hour drive, the two ended up at the West Point campus and went to the coach’s office.

They tell his secretary they’re here to see Coach Blaik. She asked if they have an appointment. They do not.

He’s busy, she said.

We’ll wait, Dawkins remembers his coach saying.

And they did.

“So now, we’ve been sitting on this sofa for an hour and I’m beginning to think he lost his mind,” Dawkins said. “So, word begins to seep out that there are these weirdos from Michigan sitting there thinking they’re going to have a visit with Blaik.”

And at about the two and a half hour mark, Blaik comes out and calls them in.

“I had probably five minutes with Coach Blaik and in those five minutes I became committed to going to West Point, it’s as simple as that,” Dawkins said.

After a stellar college career playing halfback, winning the Heisman Trophy, going 20-5-2 in his three seasons and 8-0-1 his senior season and beating Navy that year, Dawkins went on to study at the University of Oxford, England on a Rhodes Scholarship before he joined the operational force.

The football star excelled at training, becoming an infantry officer, earning his jump wings and Ranger tab. He commanded a rifle company in the 82nd Airborne Division, received his doctoral degree from Princeton University, worked on the Army Task Force to transition the service from draft to volunteer and commanded three units in his final decade – a brigade in Korea, a brigade at Fort Ord and division chief of staff with the 101st Airborne Division.

His last posting was in the Pentagon as the Deputy Director of Strategy, Plans and Policy.

But each year, no matter where he was, he would try to at least tune into the Army Navy Game, he said.

So many games, so many years, during his multiple postings in Asia, Dawkins and his fellow soldiers had to watch or listen to the game at around 2 a.m. due to the time difference.

But that hardly mattered, he said. He still remembers returning from patrols on the Korea DMZ to tune into the game.

“Because we, the people in uniform, the West Point graduates, were all over the world one of the things that gave you a sense of home was the Army Navy Game,” Dawkins said. “So, you took great pride, regardless in the challenges of doing so, you’d make it.”

Poking fun and coming to love the game

Master Chief Petty Officer of the Navy Russell Smith is from a true Navy family, he can trace that nautical heritage back five generations.

But the enlisted noncommissioned officer admits he watched the game like any other college football game before he wore a uniform and even for those first years in service.

“I didn’t really have an attachment,” Smith said.

That was until he had an Army-fan boss when he was stationed in Moscow, Russia in 2001.

That Army officer was a 1975 West Point graduate and looked forward to the game each year.

Smith took fun poking fun at the officer, telling him Navy was going to beat Army that year.

And they did.

As soon as the game ended, the officer told Smith that the next time they were both stateside they’d go to the game together.

In 2003, Smith went to his first Army Navy Game in person with his former commander.

“You walk in and there’s electricity in the air,” Smith said. “I’ve been to some rivalry games, when you walk in and see Alabama and Auburn play, you can feel the crowd’s energy, but this wasn’t so much in the crowd, it was something crackling on the field.”

Smith, who served at the Naval Academy as part of the staff four a tour, said it’s a very different feel to know that these midshipmen and cadets are teammates for 364 days of the year but then on that one day they test each other’s mettle.

“We punch each other hard because we want to be stronger when we play together in the real world with equipment,” Smith said.

With a lot of traditions, rituals and events to choose from, Smith said his favorite was the “Run the Ball” which is done by the 13th Company in the Brigade of Midshipmen.

Standing by as he was being interviewed by Navy Times on Friday was Master Chief Mike Carbone, who oversaw the 13th company when both sailors were stationed there, Smith as command master chief and Carbone as brigade master chief.

Carbone said though the company is called the “Lucky 13″ when it comes time to do the annual run, they call themselves the “Unlucky 13.” This year the relay-type, van-supported run took about 45 hours to run the ball from Annapolis, Maryland to East Rutherford, New Jersey, he said.

A different kind of student athlete

Mike Harrity did not attend West Point as a cadet. But he has worked in college athletics for more than two decades, most recently at the University of Notre Dame before taking the position of deputy director of athletics/chief operating officer for West Point in 2020.

Harrity saw a number of Notre Dame-Navy matchups, a longstanding tradition that continues in part because Notre Dame housed sailors during both world wars.

Harrity was close on details but told Army Times that a pending announcement would provide details of an Army-Notre Dame matchup in the near future.

Having spent time at Notre Dame, he thought he new traditions, and then he saw his first Army-Navy Game last year, albeit in the midst of a global pandemic.

“It’s been eye-opening,” he said. “Nothing that anybody told me about Army Navy could have prepared me for the sheer power of it.”

And he got a good result.

“Of course, Army won 15-0, so in my career Navy hasn’t scored a point against Army in a game,” he said.

Though the game can be exciting, Harrity, who focuses on the student-athletes under his direction, said that the Army-Navy Game and the players show a different kind of example for football fans.

“To watch men who have embraced that opportunity to do more, to be more to do all it takes to protect our freedom at a time when college athletics is searching for its identity,” he said. “I think its important now more than ever to continue the rivalry, which we will, but also amplify the meaning behind it.”

Lifted up

Napoleon McCallum had his pick of top college football programs when he graduated from Milford High School, having played both ways as a running back and defensive back who rushed for 1,625 yards, scored 17 touchdowns and intercepted 12 passes in his senior year alone.

But he chose the Naval Academy instead. And he excelled. While a midshipman, McCallum was a two-time consensus All-American and set an NCAA record by racking up 7,172 all-purpose yards and a career-rushing leader for the academy churning out 4,179 yards.

But when McCallum talks about the players, the teams and the games, stats, scores and trophies don’t get much room.

“This is a game where America gets to see our brightest, courageous, high character people, play in a game and play it in its purest form. These guys are not going to go play pro, they’re not worried about getting hurt and losing out on pro money, they’re going out there and giving it their heart and soul,” he said. “And then they’re going to come together after the game, for their country. Tt’s big.”

His favorite memory is being lifted up on his teammates’ shoulders after his senior Army Navy game in 1983 at the Rose Bowl stadium where he scored two touchdowns when Navy won 48-13.

While the players are the focus, all of the midshipmen and cadets hold something special that the public should understand better.

“America needs to hear about character, it’s playing for something more than yourself or your team, it’s your country,” he said.

This is a game that the President of the United States takes time to attend, he said.

He loves this year’s F/A-18-inspired uniforms because he loves Top Gun, although at first he thought of Captain America when he saw them but Cap is Army so…

“I think the [new tradition of bringing in new uniforms] is awesome. I think the more traditions we can bring in the better,” he said. “You know, it’s not just the Army Navy Game or the academy’s game, it’s for all of the people in the service.”

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.