U.S. intelligence agencies have for several years been telling anyone who will listen that for a long time now, the biggest terrorist threat to the country is domestic extremists, particularly of the right-wing variety. That threat came into sharp focus on Jan. 6, especially for the Pentagon, as it became clear that dozens of veterans and current service members were among the mob of President Donald Trump supporters that forced its way into the Capitol in an attempt to prevent Congress from certifying the 2020 election for President Joe Biden.

Defense Department officials have said many times since that leadership believes the number of extremists in the military is small, though more than what they’re comfortable with, given the disastrous effects just one ill-intentioned person in uniform can have.

But what turns someone’s feelings and beliefs from strongly held to extreme, and who decides where the line is?

Answering those questions has been a struggle for the Pentagon, but developing definitions is vital, military leaders say.

“I think it’s key to help define what we consider to be extremism” Army Gen. Richard Clarke, commander of U.S. Special Operations Command, told Military Times on May 19. “Because in this space, we don’t need to be ambiguous.”

Actions affecting unit cohesion should be a prime consideration in defining extremism, experts tell Military Times.

“The issue is performance,” Brian Michael Jenkins, a senior adviser at Rand Corp. and a former Special Forces officer, told Military Times on May 10. “And that is, to what extent may these beliefs, whatever they are, interfere with the mission of the military? Are they such that they might disrupt unit cohesion? Are they such that they will actually interfere with effective military action, whatever the job is?”

That could include bigoted beliefs about ethnic groups, religions or countries of origin, up to and including the political belief that the 2020 election was stolen and that Biden is not a legitimate commander in chief.

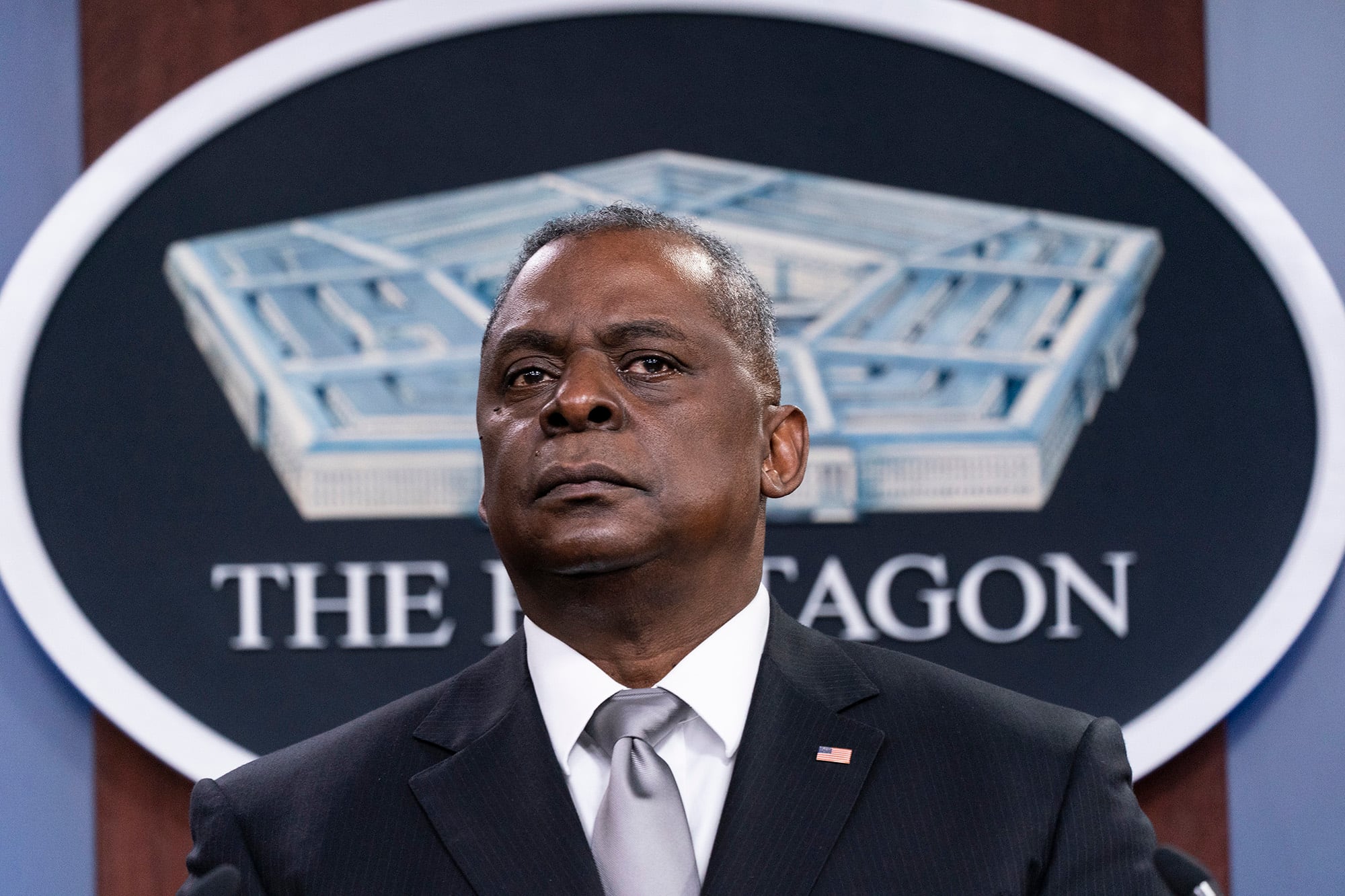

To that end, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin in April tasked a working group with creating a new definition of extremism for the department, one that will update current guidance that allows troops to belong to groups like the Ku Klux Klan or Earth Liberation Front, as long as they don’t participate in any planning, fundraising or other coordinated activities.

“Most of the most of the actual attacks that we’ve seen, over the past decade or more anyway, are perpetrated by individuals, not groups,” Seth Jones, senior vice president at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told Military Times on May 7, despite any online activity or sympathies that would suggest an affinity for one or more groups.

There are some obvious red lines, Jones said, that commanders can use when considering whether someone in their formation is a concern; threatening or advocating the use of violence against individuals or groups is an easy one.

RELATED

Sympathizing with those beliefs is a harder one to suss out, but easy to spot in online activity.

“It would be worth looking into someone that’s retweeting these kinds of things ... or having tattoos of the 14 words or ... having the anti-fascist flag burned on their forearm ― that’s a problem,” Jones said.

According to Jones’ research, 2020 saw a spike in terror plots perpetrated by active-duty and reserve troops, 6.4 percent up from 1.5 percent the previous year and none in 2018.

In addition to extremism of every stripe, DoD and the federal government in general have acknowledged the prevalence of white supremacy and white nationalism in many of the anti-government movements that have been active in recent years.

“Today, racially-or ethnically-motivated violent extremists are the most likely to conduct mass-casualty attacks against civilians, and anti-government or anti-authority violent extremists, specifically militia violent extremists, are the most likely to target law enforcement, government personnel, and government facilities,” Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas told lawmakers in May.

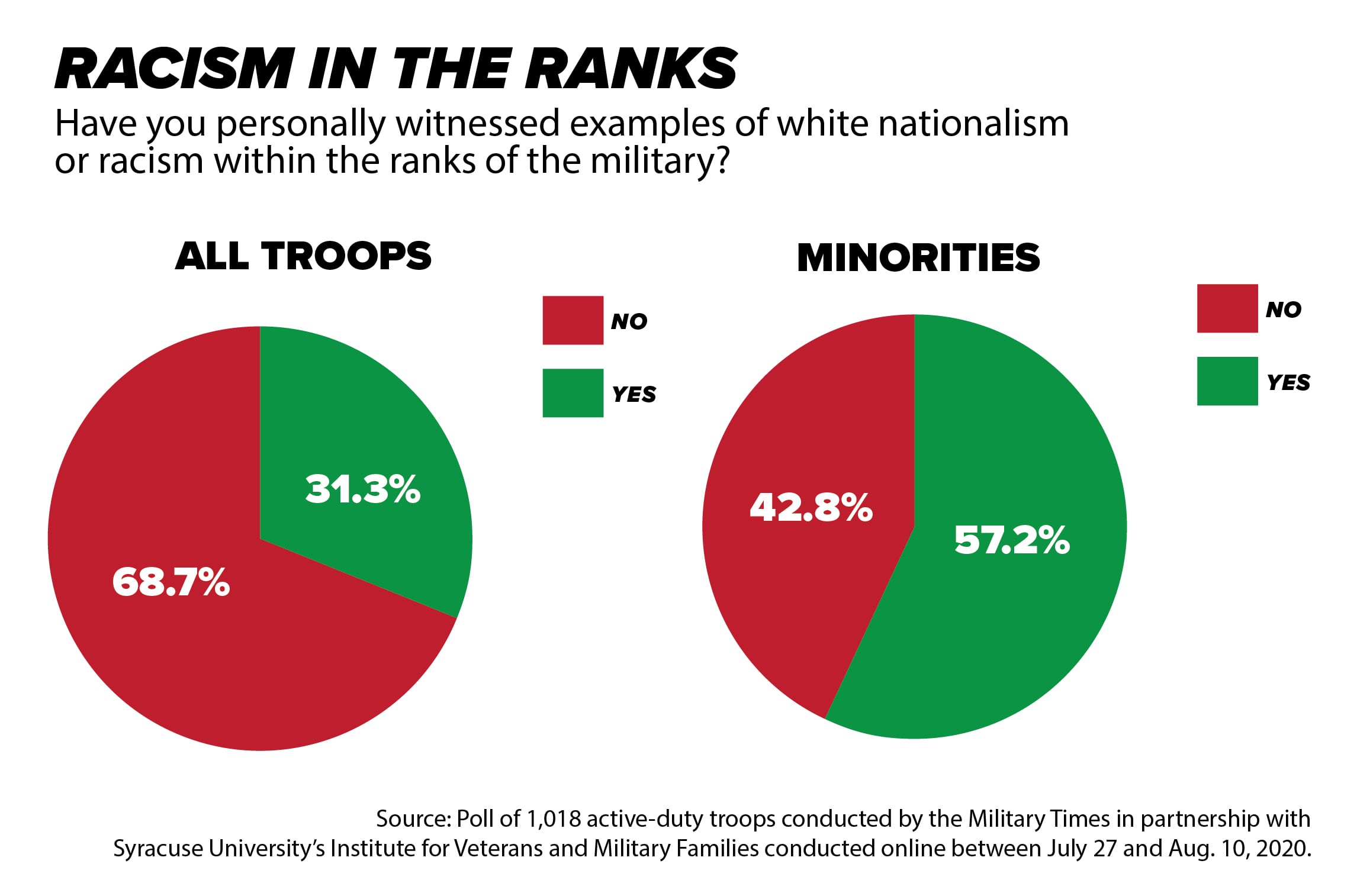

A 2020 Military Times poll found that a third of service member participants reported witnessing white supremacist language or behavior in their formations ― and that was more than half for service members of color.

“We clearly recognize the threat from domestic extremists, particularly those who espouse white supremacist or white nationalist ideologies,” a Pentagon official told reporters on Jan. 14. “We are actively involved in always trying to improve our understanding of where the threat is coming from as a means of understanding and taking action.”

And while those beliefs might not be criminal, if a service member talks openly at work about those sympathies, or posts online where colleagues can see, it can rip right through a unit’s cohesion.

“Certainly, I think most reasonable people would say, you know, that is likely to not only be offensive, but really could have a serious effect on the morale of others, the cohesion of the unit, the service,” Jenkins said. “It’s not so much trying to define extremism, as to define that what extent it becomes a legitimate concern of the military, because it interferes with the achievement of the mission.”

Case in point

The Pentagon told Congress in 2020 that it had disciplined or discharged 21 service members in the previous five years for extremist ties or leanings. Two years earlier, in response to a request from a congressman, the Pentagon said it had received 27 reports of such activity since 2013.

Among them was Lance Cpl. Vasillios G. Pistolis, who was sentenced to 28 days’ confinement and a dishonorable discharge after his ties to the Neo-Nazi Atomwaffen Division, and his participation in the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Va., came to light.

Few of the troops investigated for extremist ties see their stories publicized, though more and more are coming to light as the issue gains traction.

Maj. Jeff Poole is one such case.

In October 2019, Army Criminal Investigation Command opened an investigation into the Fort Benning, Ga., operations officer after a group of Army subreddit users put together a 75-page PowerPoint of Poole’s racist, violent rhetoric ― which included fantasizing about a revolution in which he would kill members of his chain of command if they weren’t loyal to this hypothetical insurrection.

The former intelligence soldier behind the PowerPoint told Military Times at the time that he wanted to be so thorough, and to go through CID, because was concerned that Poole’s chain of command would try to downplay his activity, perhaps slapping him with a General Officer Memorandum of Record that would allow him to stay in uniform.

He did receive a GOMOR, according to a source familiar with the proceedings, but a separation board also handed down an other-than-honorable discharge recommendation, which would block him from a host of veterans benefits.

The Army Reserve declined to confirm the outcome of Poole’s investigation or the punishments recommended.

Poole’s case is a prime example of someone not affiliated with a group, and not necessarily involved in any terror plots, but whose beliefs are anathema to serving in uniform.

There are several avenues a command can take when handling an extremism case. The Uniform Code of Military Justice has provisions for active participation in an extremist group, such as what happened in Pistolis’s case.

In the case of something grander, like participation in a plot or in a completed act of violence, the military would defer to the Justice Department.

But in the gray areas, commanders have a lot of individual leeway. They can use administrative or non-judicial punishment to tamp down on rhetoric or social media posts, or use counseling to correct a service member whose “jokes” cross the line.

Jokes like the one posted in to TikTok in 2020 by Army 2nd Lt. Nathan Freihofer, who tried out a Holocaust humor bit that he immediately followed with an admonishment to anyone who might have been offended.

The Army initiated his involuntary discharge earlier this year.

Like most policies throughout the services, any DoD extremism definition is going to lean heavily on leadership to diagnose and respond to reports.

“Then you have to leave it up to the commander’s judgment,” Jenkins said. “Is the commander’s judgment always perfect?” No.”

The stand-down was meant to lay the groundwork for the Pentagon’s new awareness of extremism, but leaving training up to each organization inevitably resulted in an uneven application of knowledge and understanding.

RELATED

Earlier this year, Military Times asked troops to weigh in on how the stand-down was going. In the feedback submitted, troops said they felt like their leadership didn’t take the training seriously, speeding through slides or cutting down what was supposed to be an all-day training to 30 minutes.

The Navy, for its part, put together a thorough presentation complete with discussion questions, but that didn’t guarantee a thorough training.

“It was very detached training and it was stated many times where the chief said, ‘I didn’t make this, we were mandated to give this training exactly like this,’ or, ‘This isn’t my opinion, it’s what is in the PowerPoint, so these are the rules,’ a first class petty officer wrote to Military Times. “At the section where it listed possible punishments for military members, he even said, ‘I’ve never even seen anyone actually charged with this.’ ”

The presentation did include some discussion questions to help clarify what’s considered free speech, which includes voicing support for the Black Lives Matter movement, displaying a Confederate flag while off-base or expressing religious views ― no matter how conservative ― as long as that doesn’t include “advocating use of illegal means to prevent others from exercising their legal rights,” such as violence or other obstruction.

But the message conveyed up the chain of command was the need for some sort of definition commanders can fall back on.

“One consistent thing that [Austin] did hear is that the force wants better guidance,” Pentagon spokesman John Kirby told reporters April 9.

Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Brown told U.S. News in April that he didn’t think a “black-and-white” definition of extremism would stick, that there would need to be a spectrum for judging rhetoric or behavior.

When asked whether he would consider extreme any airmen who don’t believe Biden is their legitimate commander in chief, and whether that is an extremist view, he declined to make a judgment.

“I stay apolitical,” he said before adding, “I have concerns about members of our nation. We have a democratic process. I stay apolitical so I don’t address that comment with our airmen. And I will tell you, I’ve not had that question.”

RELATED

His response was a departure from a statement put out by himself and his fellow members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in January, explaining that sedition and violence are not part of free speech.

“On January 20, 2021, in accordance with the Constitution, confirmed by the states and the courts, and certified by Congress, President-elect Biden will be inaugurated and will become our 46th Commander in Chief,” they wrote.

And particularly in the military, the belief that Trump won the election could call into question someone’s deference to their chain of command.

“My view is, is if if somebody believes that Joe Biden is an illegitimate president, then I think it’s time for you to seriously consider whether it’s right for you to serve in the military, because that’s your commander,” Jones said.

There is no set deadline for the working group to submit their extremism definition, Kirby told Military Times. The team has until mid-July to report back to Austin with their progress, along with recommendations for mid- and long-term projects.

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.