WASHINGTON — The oldest prisoner at the Guantanamo Bay detention center went to his latest review board hearing with a degree of hope, something that has been scarce during his 16 years locked up without charges at the U.S. base in Cuba.

Saifullah Paracha, a 73-year-old Pakistani with diabetes and a heart condition, had two things going for him that he didn’t have at previous hearings: a favorable legal development and the election of Joe Biden.

President Donald Trump had effectively ended the Obama administration’s practice of reviewing the cases of men held at Guantanamo and releasing them if imprisonment was no longer deemed necessary. Now there’s hope that will resume under Biden.

“I am more hopeful now simply because we have an administration to look forward to that isn’t dead set on ignoring the existing review process,” Paracha’s attorney, Shelby Sullivan-Bennis, said by phone from the base on Nov. 19 after the hearing. “The simple existence of that on the horizon I think is hope for all of us.”

RELATED

Guantanamo was once a source of global outrage and a symbol of U.S. excess in response to terrorism. But it largely faded from the headlines after President Barack Obama failed to close it, even as 40 men continue to be detained there.

Those pushing for its closure now see a window of opportunity, hoping Biden’s administration will find a way to prosecute those who can be prosecuted and release the rest, extricating the U.S. from a detention center that costs more than $445 million per year.

Biden’s precise intentions for Guantanamo remain unclear. Transition spokesman Ned Price said the president-elect supports closing it, but it would be inappropriate to discuss his plans in detail before he’s in office.

His reticence is actually welcome to those who have pressed to close Guantanamo. Obama’s early pledge to close it is now seen as a strategic mistake that undercut what had been a bipartisan issue.

“I think it’s more likely to close if it doesn’t become a huge press issue,” said Andrea Prasow, deputy Washington director at Human Rights Watch.

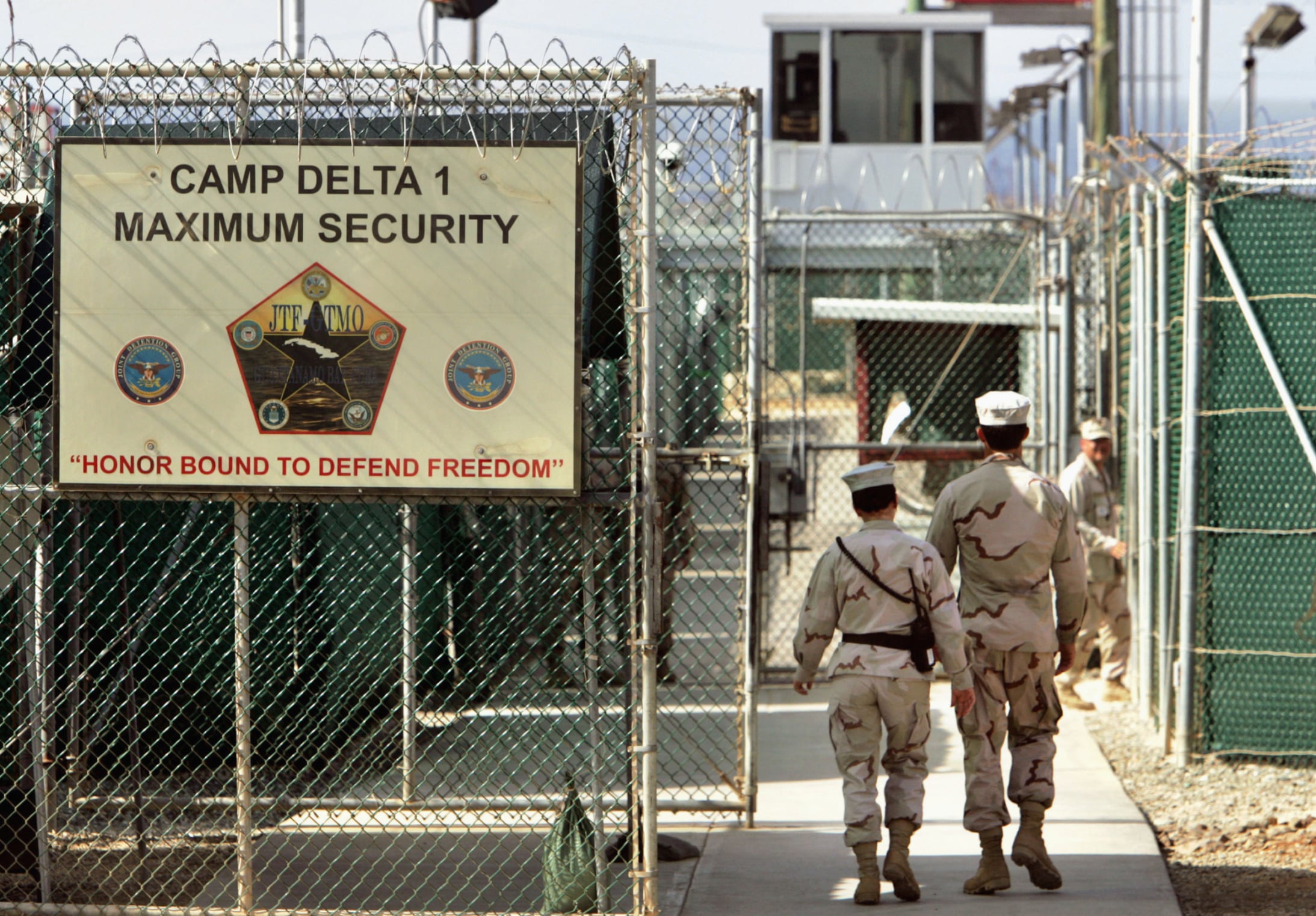

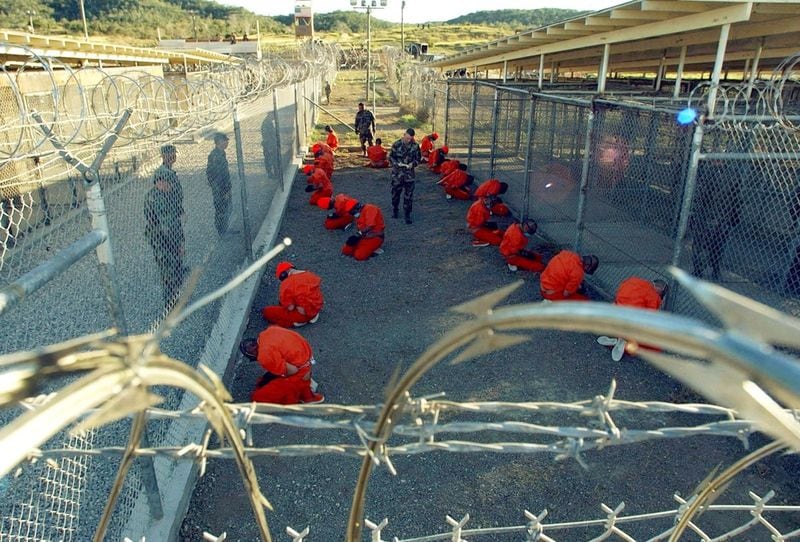

The detention center opened in 2002. President George W. Bush’s administration transformed what had been a sleepy Navy outpost on Cuba’s southeastern tip into a place to interrogate and imprison people suspected of links to al-Qaida and the Taliban after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks.

U.S. authorities maintain the men can be held as “law of war” detainees, remaining in custody for the duration of hostilities, an open-ended prospect.

At its peak in 2003 — the year Paracha was captured in Thailand because of suspected ties to al-Qaida — Guantanamo held about 700 prisoners from nearly 50 countries. Bush announced his intention to close it, though 242 were still held there when his presidency ended.

The Obama administration, seeking to allay concerns that some of those released had “returned to the fight,” set up a process to ensure those repatriated or resettled in third countries no longer posed a threat. It also planned to try some of the men in federal court.

But his closure effort was thwarted when Congress barred the transfer of prisoners from Guantanamo to the U.S., including for prosecution or medical care. Obama ended up releasing 197 prisoners, leaving 41 for Trump.

RELATED

Trump in his 2016 campaign promised to “load” Guantanamo with “some bad dudes,” but largely ignored the issue after rescinding Obama’s policies. His administration approved a single release, a Saudi who pleaded guilty before a military commission.

Of those 40 remaining, seven men have cases pending before a military commission. They include five men accused of planning and supporting the Sept. 11 attacks. Additionally, there are two prisoners who were convicted by commission and three facing potential prosecution for the 2002 Bali bombing.

Commission proceedings, including death penalty cases related to the Sept. 11 attacks, have bogged down as the defense fights to exclude evidence that resulted from torture. Trials are likely far in the future and would inevitably be followed by years of appeals.

Defense attorneys say the incoming administration could authorize more military commission plea deals. Some have also suggested Guantanamo detainees could plead guilty in federal court by video and serve any remaining sentence in other countries, so they wouldn’t enter the United States.

Detainee advocates also say Biden could defy Congress and bring prisoners to the U.S., arguing that the ban wouldn’t stand up in court.

“It’s either do something about it or they die there without charge,” said Wells Dixon, a lawyer for two prisoners, including one who has pleaded guilty in the military commission and is awaiting sentencing.

The remaining detainees include five who had been cleared for release before Trump took office and have languished since. Advocates want the Biden administration to review the rest, noting that many, had they been convicted in federal court, would have served their sentences and been released at this point.

“Whittle it down to the folks who are being prosecuted and either prosecute them or don’t, but don’t just hang on to them,” said Joseph Margulies, a Cornell Law School professor who has represented one prisoner. “At great expense, we walk around with this thing around our necks. It does no good. It has no role for national security. It’s just a big black stain that provides no benefit whatsoever.”

Over the years, nine prisoners have died at Guantanamo: seven from apparent suicide, one from cancer and one from a heart attack.

Paracha’s attorney raised his health issues, which include a heart attack in 2006, at his review board, speaking by secure teleconference with U.S. security and defense agencies.

She also raised an important legal development. Paracha, who lived in the U.S. and owned property in New York City, was a wealthy businessman in Pakistan. Authorities say he was an al-Qaida “facilitator” who helped two of the Sept. 11 conspirators with a financial transaction. He says he didn’t know they were al-Qaida and denies any involvement in terrorism.

Uzair Paracha, his son, was convicted in 2005 in federal court in New York of providing support to terrorism, based in part on the same witnesses held at Guantanamo that the U.S. has relied on to justify holding his father. In March, after a judge threw out those witness accounts and the government decided not to seek a new trial, Uzair Paracha was released and sent back to Pakistan.

Had his father been convicted in the U.S., his fate might have been the same. Instead, it will likely be in Biden’s hands and, Sullivan-Bennis said, time is of the essence. “It could be a death sentence.”