The plan was simple, but perilous. Some 300 heavily armed volunteers would sneak into Venezuela from the northern tip of South America. Along the way, they would raid military bases in the socialist country and ignite a popular rebellion that would end in President Nicolás Maduro’s arrest.

What could go wrong? As it turns out, pretty much everything.

The ringleader of the plot is now jailed in the U.S. on narcotics charges. Authorities in the U.S. and Colombia are asking questions about the role of his muscular American adviser, a former Green Beret. And dozens of desperate combatants who flocked to secret training camps in Colombia said they have been left to fend for themselves amid the coronavirus pandemic.

The failed attempt to start an uprising collapsed under the collective weight of skimpy planning, feuding among opposition politicians and a poorly trained force that stood little chance of beating the Venezuelan military.

“You’re not going to take out Maduro with 300 hungry, untrained men,” said Ephraim Mattos, a former U.S. Navy SEAL who trained some of the would-be combatants in first aid.

This bizarre, untold story of a call to arms that crashed before it launched is drawn from interviews with more than 30 Maduro opponents and aspiring freedom fighters who were directly involved in or familiar with its planning. Most spoke on condition of anonymity, fearing retaliation.

When hints of the conspiracy surfaced last month, the Maduro-controlled state media portrayed it as an invasion ginned up by the CIA, like the Cuban Bay of Pigs fiasco of 1961. An Associated Press investigation found no evidence of U.S. government involvement in the plot. Nevertheless, interviews revealed that leaders of Venezuela’s U.S.-backed opposition knew of the covert force, even if they dismissed its prospects.

Planning for the incursion began after an April 30, 2019, barracks revolt by a cadre of soldiers who swore loyalty to Maduro’s would-be replacement, Juan Guaidó, the opposition leader recognized by the U.S. and some 60 other nations as Venezuela’s rightful leader. Contrary to U.S. expectations at the time, key Maduro aides never joined with the opposition and the government quickly quashed the uprising.

A few weeks later, some soldiers and politicians involved in the failed rebellion retreated to the JW Marriott in Bogota, Colombia. The hotel was a center of intrigue among Venezuelan exiles. For this occasion, conference rooms were reserved for what one participant described as the “Star Wars summit of anti-Maduro goofballs” — military deserters accused of drug trafficking, shady financiers and former Maduro officials seeking redemption.

Among those angling in the open lobby was Jordan Goudreau, an American citizen and three-time Bronze Star recipient for bravery in Iraq and Afghanistan, where he served as a medic in U.S. Army special forces, according to five people who met with the former soldier.

Those he interacted with in the U.S. and Colombia described him in interviews alternately as a freedom-loving patriot, a mercenary and a gifted warrior scarred by battle and in way over his head.

Two former special forces colleagues said Goudreau was always at the top of his class: a cell leader with a superb intellect for handling sources, an amazing shot and a devoted mixed martial arts fighter who still cut his hair high and tight.

At the end of an otherwise distinguished military career, the Canadian-born Goudreau was investigated in 2013 for allegedly defrauding the Army of $62,000 in housing stipends. Goudreau said the investigation was closed with no charges.

After retiring in 2016, he worked as a private security contractor in Puerto Rico following Hurricane Maria. In 2018, he set up Silvercorp USA, a private security firm, near his home on Florida’s Space Coast to embed counter-terror agents in schools disguised as teachers. The company’s website features photos and videos of Goudreau firing machine guns in battle, running shirtless up a pyramid, flying on a private jet and sporting a military backpack with a rolled-up American flag.

Silvercorp’s website touts operations in more than 50 countries, with an advisory team made up of former diplomats, experienced military strategists and heads of multinational corporations -- none of them named. It claims to have “led international security teams” for the president of the United States.

Goudreau, 43, declined to be interviewed. In a written statement, he said that “Silvercorp cannot disclose the identities of its network of sources, assets and advisors due to the nature of our work” and, more generally, “would never confirm nor deny any activities in any operational realm. No inference should be drawn from this response.”

`CONTROLLING CHAOS'

Goudreau’s focus on Venezuela started in February 2019, when he worked security at a concert in support of Guaidó organized by British billionaire Richard Branson on the Venezuelan-Colombian border.

“Controlling chaos on the Venezuela border where a dictator looks on with apprehension,” he wrote in a photo of himself on the concert stage posted to his Instagram account.

“He was always chasing the golden BB,” said Drew White, a former business partner at Silvercorp, using military slang for a one-in-a-million shot. White said he broke with his former special forces comrade last fall when Goudreau asked for help raising money to fund his regime change initiative.

“As supportive as you want to be as a friend, his head wasn’t in the world of reality," said White. "Nothing he said lined up.”

According to White, Goudreau came back from the concert looking to capitalize on the Trump administration’s growing interest in toppling Maduro.

He had been introduced to Keith Schiller, President Donald Trump’s longtime bodyguard, through someone who worked in private security. Schiller attended a March 2019 event at the University Club in Washington for potential donors with activist Lester Toledo, then Guaidó’s coordinator for the delivery of humanitarian aid.

Last May, Goudreau accompanied Schiller to a meeting in Miami with representatives of Guaidó. There was a lively discussion with Schiller about the need to beef up security for Guaidó and his growing team of advisers inside Venezuela and across the world, according to a person familiar with the meeting. Schiller thought Goudreau was naive and in over his head. He cut off all contact following the meeting, said a person close to the former White House official.

In Bogota, it was Toledo who introduced Goudreau to a rebellious former Venezuelan military officer the American would come to trust above all others — Cliver Alcalá, ringleader of the Venezuelan military deserters.

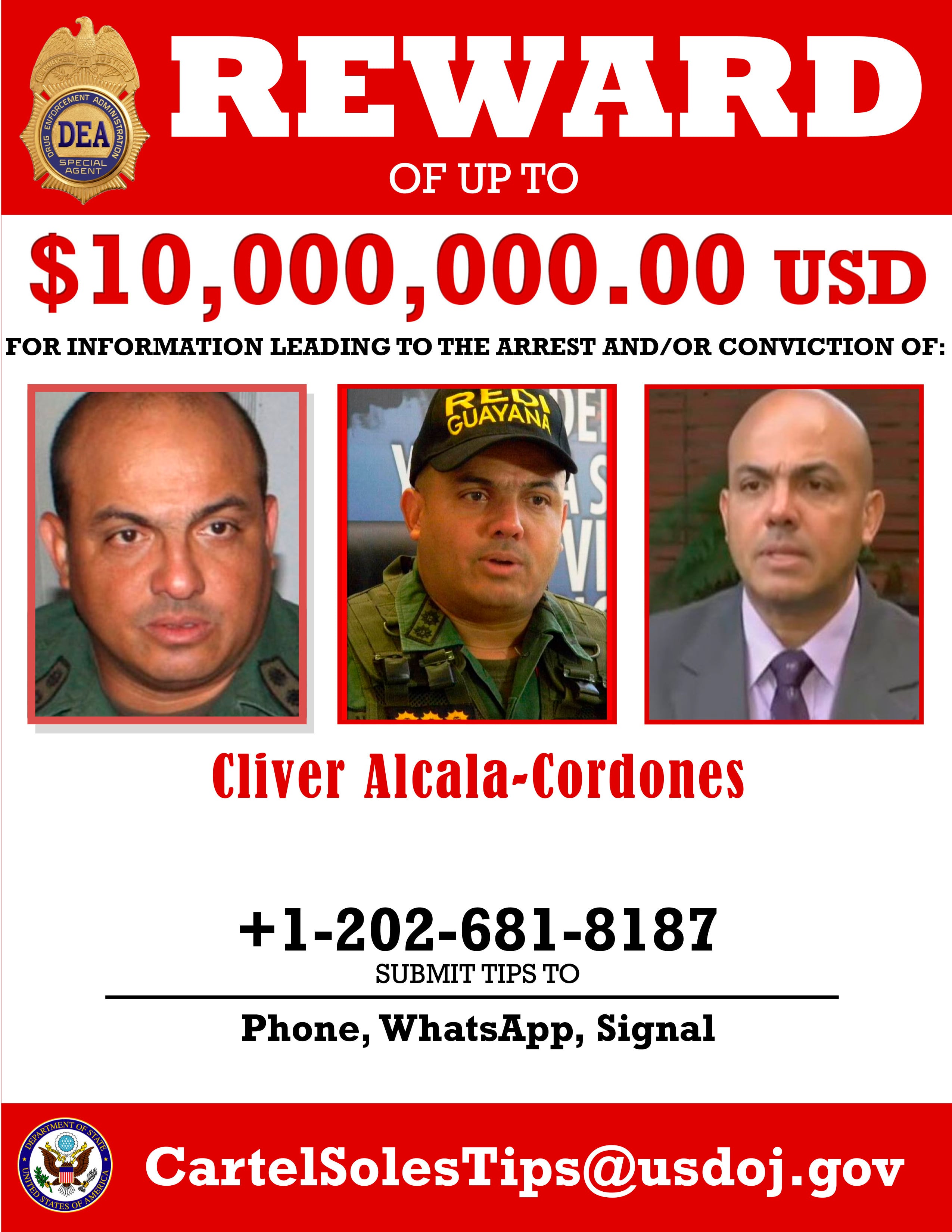

Alcalá, a retired major general in Venezuela’s army, seemed an unlikely hero to restore democracy to his homeland. In 2011, he was sanctioned by the U.S. for allegedly supplying FARC guerrillas in Colombia with surface-to-air missiles in exchange for cocaine. And last month, Alcalá was indicted by U.S. prosecutors alongside Maduro as one of the architects of a narcoterrorist conspiracy that allegedly sent 250 metric tons of cocaine every year to the U.S.

Alcalá is now in federal custody in New York awaiting trial. But before his surrender in Colombia, where he had been living since 2018, he had emerged as a forceful opponent of Maduro, not shy about urging military force.

Over two days of meetings with Goudreau and Toledo at the JW Marriott, Alcalá explained how he had selected 300 combatants from among the throngs of low-ranking soldiers who abandoned Maduro and fled to Colombia in the early days of Guaidó’s uprising, said three people who participated in the meeting and insisted on anonymity to discuss sensitive conversations.

Alcalá said several dozen men were already living in three camps he maintained in and around the desert-like La Guajira peninsula that Colombia shares with Venezuela, the three said. Among the combatants in the camps was an exiled national guardsman accused of participating in a 2018 drone attack on Maduro.

Goudreau told Alcalá his company could prepare the men for battle, according to the three sources. The two sides discussed weapons and equipment for the volunteer army, with Goudreau estimating a budget of around $1.5 million for a rapid strike operation.

Goudreau told participants at the meeting that he had high-level contacts in the Trump administration who could assist the effort, although he offered few details, the three people said. Over time, many of the people involved in the plan to overthrow Maduro would come to doubt his word.

From the outset, the audacious plan split an opposition coalition already sharply divided by egos and strategy. There were concerns that Alcalá, with a murky past and ties to the regime through a brother who was Maduro’s ambassador to Iran, couldn’t be trusted. Others worried about going behind the backs of their Colombian allies and the U.S. government.

But Goudreau didn’t share the concerns about Alcalá, according to two people close to the former American solider. Over time, he would come to share Alcalá’s mistrust of the opposition, whose talk of restoring democracy was belied by what he saw as festering corruption and closed-door deal making with the regime, they said.

More importantly to Goudreau, Alcalá retained influence in the armed forces that Maduro’s opponents, mostly civilian elites, lacked. He also knew the terrain, having served as the top commander along the border.

“We needed someone who knew the monster from the inside,” recalled one exiled former officer who joined the plot.

Guaidó’s envoys, including Toledo, ended contact with Goudreau after the Bogota meeting because they believed it was a suicide mission, according to three people close to the opposition leader.

Undeterred, Goudreau returned to Colombia with four associates, all of them U.S. combat veterans, and begin working directly with Alcalá.

Alcalá and Goudreau revealed little about their military plans when they toured the camps. Some of the would-be combatants were told by the two men that the rag-tag army would cross the border in a heavily armed convoy and sweep into Caracas within 96 hours, according to multiple soldiers at the camps. Goudreau told the volunteers that — once challenged in battle — Maduro’s food-deprived, demoralized military would collapse like dominoes, several of the soldiers said.

NO CHANCE TO SUCCEED

Many saw the plan as foolhardy and there appears to have been no serious attempt to seek U.S. military support.

“There was no chance they were going to succeed without direct U.S. military intervention,” said Mattos, the former Navy SEAL who spent two weeks in September training the volunteers in basic tactical medicine on behalf of his non-profit, which works in combat zones.

Mattos visited the camps after hearing about them from a friend working in Colombia. He said he never met Goudreau.

Mattos said he was surprised by the barren conditions. There was no running water and men were sleeping on the floors, skipping meals and training with sawed-off broomsticks in place of assault rifles. Five Belgian shepherds trained to sniff out explosives were as poorly fed as their handlers and had to be given away.

Mattos said he grew wary as the men recalled how Goudreau had boasted to them of having protected Trump and told them he was readying a shipment of weapons and arranging aerial support for an eventual assault of Maduro’s compound.

The volunteers also shared with Mattos a three-page document listing supplies needed for a three-week operation, which he provided to AP. Items included 320 M4 assault rifles, an anti-tank rocket launcher, Zodiac boats, $1 million in cash and state-of-the-art night vision goggles. The document’s metadata indicates it was created by Goudreau on June 16.

“Unfortunately, there’s a lot of cowboys in this business who try to peddle their military credentials into a big pay day,” said Mattos.

AP found no indication U.S. officials sponsored Goudreau’s actions nor that Trump has authorized covert operations against Maduro, something that requires congressional notification.

But Colombian authorities were aware of his movements, as were prominent opposition politicians in Venezuela and exiles in Bogota, some of whom shared their findings with U.S. officials, according to two people familiar with the discussions.

True to his reputation as a self-absorbed loose cannon, Alcalá openly touted his plans for an incursion in a June meeting with Colombia’s National Intelligence Directorate and appealed for their support, said a former Colombian official familiar with the conversation. Alcalá also boasted about his relationship with Goudreau, describing him as a former CIA agent.

When the Colombians checked with their CIA counterparts in Bogota, they were told that the former Green Beret was never an agent. Alcalá was then told by his hosts to stop talking about an invasion or face expulsion, the former Colombian official said.

It’s unclear where Alcalá and Goudreau got their backing, and whatever money was collected for the initiative appears to have been meager. One person who allegedly promised support was Roen Kraft, an eccentric descendant of the cheese-making family who — along with former Trump bodyguard Schiller — was among those meeting with opposition envoys in Miami and Washington.

At some point, Kraft started raising money among his own circle of fellow trust-fund friends for what he described as a “private coup” to be carried out by Silvercorp, according to two businessmen whom he asked for money.

Kraft allegedly lured prospective donors with the promise of preferential access to negotiate deals in the energy and mining sectors with an eventual Guaidó government, said one of the businessmen. He provided AP a two-page, unsigned draft memorandum for a six-figure commitment he said was sent by Kraft in October in which he represents himself as the “prime contractor” of Venezuela.

But it was never clear if Kraft really had the inside track with the Venezuelans.

In a phone interview with AP, Kraft acknowledged meeting with Goudreau three times last year. But he said the two never did any business together and only discussed the delivery of humanitarian aid for Venezuela. He said Goudreau broke off all communications with him on Oct. 14, when it seemed he was intent on a military action.

“I never gave him any money,” said Kraft.

`WE KNEW EVERYTHING'

Back in Colombia, more recruits were arriving to the three camps — even if the promised money didn’t. Goudreau tried to bring a semblance of order. Uniforms were provided, daily exercise routines intensified and Silvercorp instructed the would-be warriors in close quarter combat.

Goudreau is “more of a Venezuelan patriot than many Venezuelans,” said Hernán Alemán, a lawmaker from western Zulia state and one of a few politicians to openly embrace the clandestine mission.

Alemán said in an interview that neither the U.S. nor the Colombian governments were involved in the plot to overthrow Maduro. He claims he tried to speak several times to Guaidó about the plan but said the opposition leader showed little interest.

“Lots of people knew about it, but they didn’t support us,” he said. “They were too afraid.”

The plot quickly crumbled in early March when one of the volunteer combatants was arrested after sneaking across the border into Venezuela from Colombia.

Shortly after, Colombian police stopped a truck transporting a cache of brand new weapons and tactical equipment worth around $150,000, including spotting scopes, night vision goggles, two-way radios and 26 American-made assault rifles with the serial numbers rubbed off. Fifteen brown-colored helmets were manufactured by High-End Defense Solutions, a Miami-based military equipment vendor owned by a Venezuelan immigrant family.

High-End Defense Solutions is the same company that Goudreau visited in November and December, allegedly to source weapons, according to two former Venezuelan soldiers who claim to have helped the American select the gear but later had a bitter falling out with Goudreau amid accusations that they were moles for Maduro.

Company owner Mark Von Reitzenstein did not respond to repeated email and phone requests seeking comment.

Alcalá claimed ownership of the weapons shortly before surrendering to face the U.S. drug charges, saying they belonged to the “Venezuelan people.” He also lashed out against Guaidó, accusing him of betraying a contract signed between his “American advisers” and J.J. Rendon, a political strategist in Miami appointed by Guaidó to help force Maduro from power.

“We had everything ready,” lamented Alcalá in a video published on social media. “But circumstances that have plagued us throughout this fight against the regime generated leaks from the very heart of the opposition, the part that wants to coexist with Maduro.”

Through a spokesman, Guaidó stood by comments made to Colombian media that he never signed any contract of the kind described by Alcalá, whom he said he doesn’t know. Rendon said his work for Guaidó is confidential and he would be required to deny any contract, whether or not it exists.

Meanwhile, Alcalá has offered no evidence and the alleged contract has yet to emerge, though AP repeatedly asked Goudreau for a copy.

In the aftermath of Alcalá’s arrest, the would-be insurrection appears to have disbanded. As the coronavirus spreads, several of the remaining combatants have fled the camps and fanned out across Colombia, reconnecting with loved ones and figuring out their next steps. Most are broke, facing investigation by Colombian police and frustrated with Goudreau, whom they blame for leading them astray.

Meanwhile, the socialist leadership in Caracas couldn’t help but gloat.

Diosdado Cabello, the No. 2 most powerful person in the country and eminence grise of Venezuela’s vast intelligence network, insisted that the government had infiltrated the plot for months.

“We knew everything,” said Cabello. “Some of their meetings we had to pay for. That’s how infiltrated they were.”

Investigative researcher Randy Herschaft in New York and investigative reporter James LaPorta in Delray Beach, Florida, contributed to this report.