A Texas-based soldier said he moved out of his apartment near post and sent his car and belongings out-of-state, where his wife lives with their two children, in anticipation of a deployment.

“I moved out of the cheap apartment and onto a friend’s couch, with only two bags of uniforms and a few pairs of civilian clothes in preparation for my flight,” scheduled for last Friday, he said in an email to Military Times.

But then the stop-movement order came down, canceling the deployment and preventing him from traveling out of state to get his car and belongings.

“I am still expected to make it to work and staff duty, so I’ve been walking and biking an hour both ways,” he said. “I also had to re-sign my apartment lease, and rent has increased.”

Though there is some financial relief available for troops, it does not necessarily cover the two households he has to maintain.

“Most soldiers drink when they get to this level of helplessness, but I can’t even afford alcohol right now,” he said.

On even the best day, top-down guidance from the Pentagon can be complicated to implement and confusing to troops at the small-unit level.

But in the midst of a deadly pandemic, the Pentagon’s last week’s stop-movement order was the culmination of a series of travel restrictions that have thrown service members and their families into turmoil. In many ways, it has flipped the table on daily life in the military ― and equally alarming to some troops, not affected daily operations as much as some feel it should.

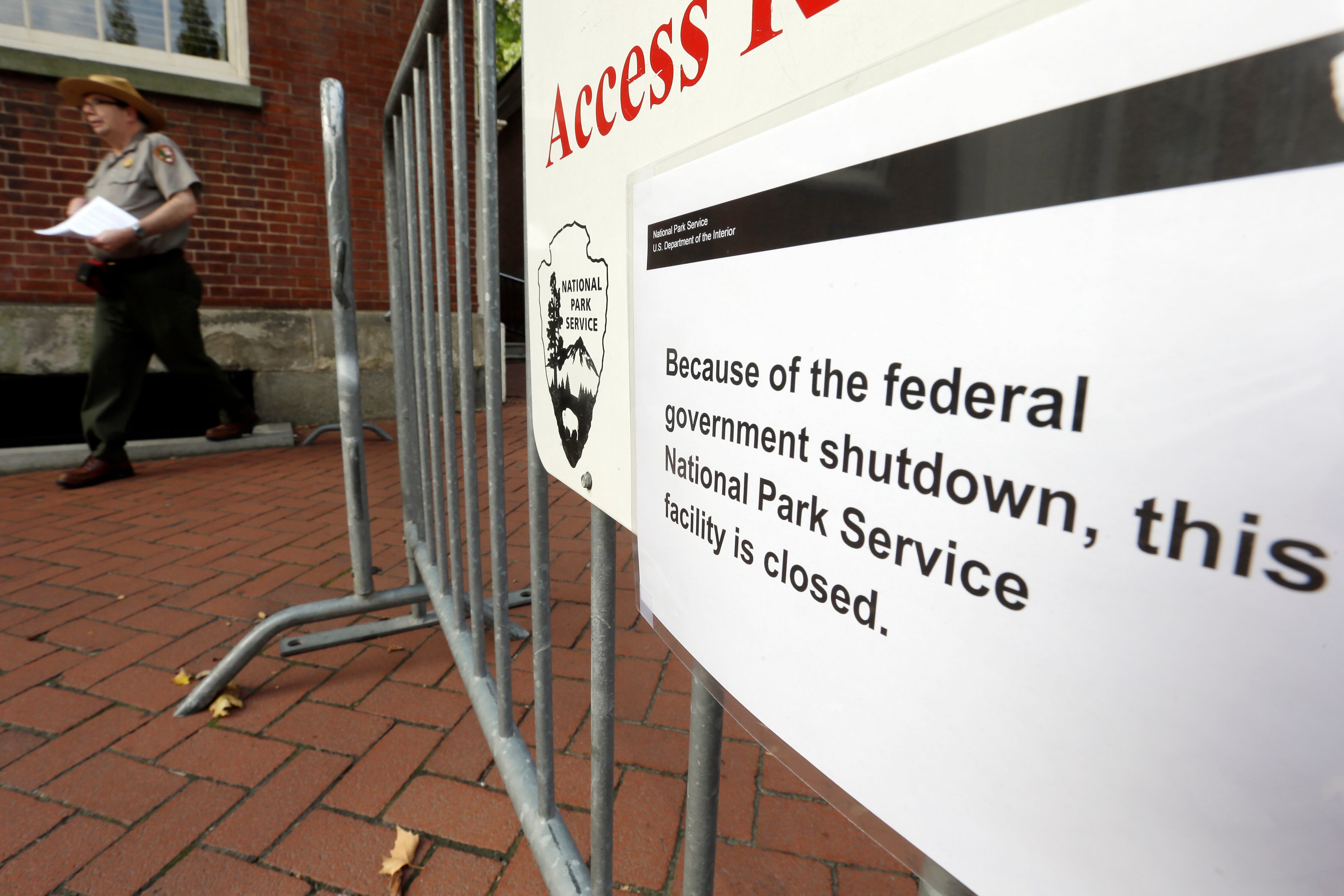

What started as holds on permanent change-of-station moves and temporary duty travel earlier this month evolved into a near-total ban on any travel, including delayed and extended deployments. Caught in the middle are thousands of troops and family members whose lives are already complicated by military service.

“We are committed to taking every precaution to ensure the health and wellbeing of our people,” Defense Secretary Mark Esper wrote in a Friday memo to the force. “That is why we have imposed restrictions on all domestic and international travel. We understand the impact of delaying PCS moves, modifying training exercises, and temporarily closing some installation services. These decisions are necessary to mitigate risk to you and your families, while we work to ease the burden on the force as much as possible.”

For some, that meant troops trapped abroad, in Europe or South Korea or in far-flung parts of the U.S., after packing up their households and sending their families on to new stateside duty stations.

And while Esper has authorized local commanders to provide special pay to help service members cover unexpected expenses, as well as some exceptions to the ban for serious hardships, each of those cases has to be individually approved, which takes time.

All service members who reached out to Military Times requested to have their names withheld, most specifically because of fear of retribution from their units over speaking out.

“Alongside family strife, Marines and sailors have not received one ounce of legitimate word from any level of the chain of command,” one Marine reader wrote to Military Times, as his unit’s Europe forward-deployment has been extended from six months to at least eight. “We hear nothing but rumors from all levels of the chain of command. Rumors passed among Marines and sailors sound illegitimate and outrageous but slowly become more true ... due to our lack of knowledge regarding the situation in our area of operations, Camp Lejeune, and the United States as a whole.”

Spokespeople for the Office of the Secretary of Defense and the Joint Staff did not respond to a request for comment.

In another case, a soldier deployed to the U.S.-Mexico border mission is about to miss the birth of his child, as his leave to visit his wife ― also a soldier, who has been alone with their two children during his deployment ― has been canceled.

“We obviously didn’t have other plans because a pandemic is something you don’t plan for,” she told Military Times. “However, this is causing us to spend thousands of dollars on hiring additional babysitters and doulas to come into my house to help me care for my family, when we could be lowering the risk by only bringing one person ― my husband and father to my children.”

RELATED

For some, the order is affecting both a deployment and causing a family separation. A San Diego-based Marine who wrote to Military Times said that not only has the pandemic canceled his unit’s forward-deployment, it’s preventing him from visiting his wife and children, who live outside the 50-mile local travel radius allowed under the policy.

“All of our hard work and practice has now been, in my opinion, potentially for nothing,” he said.

But, he added, the ban didn’t seem to be affecting mission readiness, as day-to-day life in the unit hadn’t changed much ― despite one confirmed case within the formation.

“... our unit is operating at its normal pace as if this didn’t exist,” he said. “The only impact it has is on the morale of the troops.”

No ‘blanket policy’

For most of the past month, regional commands have been getting the word out about social distancing, following the lead of U.S. Forces Korea, which shut down most movement and started screening every visitor coming onto installations in the early days of the outbreak in Daegu.

“... I can’t put out a blanket policy, if you will, that we would then apply to everybody, because every situation’s different,” Esper told Military Times on March 23. “Tell me how I would implement 6-feet distancing in an attack submarine? Or how do I do that in a bomber with two pilots sitting side-by-side?”

And for much of the month, stories and photos circulated of unit physical fitness sessions, staff meetings and accountability formations, as if nothing had changed.

On March 24, Esper took a stronger tone.

“You take prudent measures as best you can given the situation you’re in,” he said in a live town hall meeting, broadcast from the Pentagon’s briefing room. “If you can avoid putting a large number of people in small rooms, you should do it.”

That has proven particularly difficult in the Navy. Aside from the confined spaces aboard ships, Esper’s travel ban does not extend to ship deployments as long as the crews practice a two-week quarantine before getting underway, between port calls and upon homecoming.

“The virus has impacted our command but I believe my superiors do not think it warrants the halt of any operational exercises,” one San Diego-based sailor wrote. “For example, we are planning on having a fast cruise on the pier at a time when we should be practicing social distancing, and scheduled to go underway for about three weeks.”

Meanwhile, dozens of sailors about the aircraft carrier Theodore Roosevelt have come down with COVID-19, sidelining the 4,000-sailor crew in Guam and prompting its skipper to call on the Navy’s most senior officials for action.

"... we are not at war, and therefore cannot allow a single sailor to perish as a result of this pandemic unnecessarily,” Crozier wrote in a Monday letter to Navy officials. “Decisive action is required now in order to comply with CDC and [Navy] guidance and prevent tragic outcomes.”

Asked about his response to the letter, Esper told the CBS Evening News on Tuesday that he hadn’t read it in detail.

“I have not had a chance to read that letter, read it in detail,” Esper said. "Again, I’m going to rely on the Navy chain of command to go out there to assess the situation and make sure they provide the captain and the crew all the support they need to get the sailors healthy.”

Preventing the spread of the virus is also affecting pay for some service members. National Guard and reserve unit drills have been canceled until further notice, and with them the pay that those troops count on for their monthly weekend activation.

The same goes for some who are just starting their careers.

“Because of this stop-movement I cannot start active duty,” a recently commissioned Air Force second lieutenant wrote. “So I’m without benefits or a paycheck and my recent part-time job shut down weeks ago.”

But the most frustrating part, echoed by all, was the same feeling that most Americans have been feeling ― an abject uncertainty about when all of the uncertainty might end.

“Again, these are only rumors, but the difference between truth and lies are slowly beginning to blend together,” one Marine wrote. “Due to the above mentioned, I believe our effectiveness and readiness has been greatly reduced.”

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.