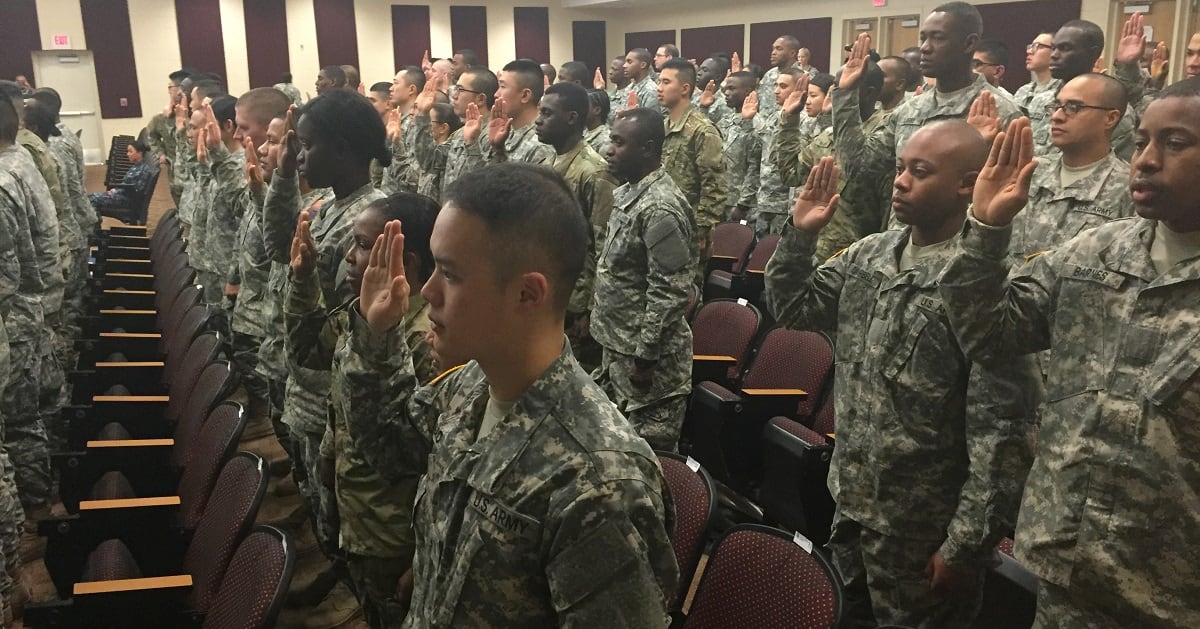

The federal government is rolling back protections that have held off deportations for non-citizen service members, their families and veterans, according to a top immigration lawyer.

Memos are circulating among Homeland Security and Defense Department personnel, as well as lawyers who handle service member immigration issues, announcing the end of a handful of policies that have allowed thousands of people to stay in the U.S. while they sort out their resident status.

“I wanted to confirm that this was all true, so I started calling a few people, and I got confirmation in various emails that this was all true,” Margaret Stock, an Alaska-based attorney, told Military Times in a Thursday phone interview.

Spokespeople for the White House, DHS and DoD declined to comment about the policies, which include deferred action and parole in place, temporary legal residency statuses granted to undocumented immigrants on a case-by-case basis.

Deferred action grants a renewable two-year legal residency, including the ability to work legally, as in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals or DACA program that has made headlines in recent years.

Parole in place has been used specifically for service members’ families, granting renewable year-long legal residency and the ability to work legally.

Exceptions written into immigration policy have allowed both of those options for service members, their family members and troops, but the administration’s latest moves do away with them.

“It used to be, under the Bush administration and the Obama administration, that they would terminate removal proceedings for military members and their family members, and that’s changed under Trump," Stock said, adding that service members and family members have been put into removal proceedings well before these memos were drafted.

Stock first got wind of the changes on Saturday, at an American Immigration Lawyers Association meeting. There are about four weeks until the new rules go into effect, she said, so those affected are scrambling to get their requests approved before late July.

The memos show that both deferred action and parole in place are being eliminated for service members, veterans and their families, "with the exception of the immediate relatives of United States citizens ― and those are people who don’t actually need deferred action, for the most part,” because they have another path to legal residency, Stock said.

That covers military veterans, current service members and family members ― including parents, spouses and children ― in both the active and reserve components, she said.

“And then they’re also going to eliminate parole in place for family members, veterans, reservists, National Guard and all active duty people,” she added.

The changes will also affect troops serving under the Military Accessions Vital to National Interest program, which allows certain non-citizens to serve in the military and eventually apply for citizenship.

The policy was written, she said, after the case of a green card-holding sailor who testified before Congress: In her case, she had gone to on-base legal services to ask if she needed to renew her green card, and told by a judge advocate that it wasn’t necessary, because she was in the citizenship application process.

So the green card lapsed, and DHS opened removal proceedings, forcing her to take leave fly to California from Norfolk, Virginia, to attend hearings to clear it up.

Consequences

“We’re going to see a lot more of that kind of stuff happening now,” Stock said.

DoD has also since stopped expedited citizenship approvals for service members, she added, because “the solution was we used to have was to just naturalize the troops and we wouldn’t have to worry about them getting deported.”

DoD has also forced discharges of MAVNI troops with foreign-born parents, Stock said.

RELATED

“They’re immigrants in the military. They knew they had foreign parents when they enlisted them, but they now claim that’s some dangerous thing, to have foreign parents," she said.

It all adds up to huge headaches for service members and their commands, Stock said.

“The reason we came up with all these policies was to stop this kind of stuff, because it was creating havoc in the ranks,” she said.

If the policy changes result in deportations, it will likely be years before their are carried out, Stock said.

“Deportations don’t happen immediately in America. They’re a lengthy process,” she said, involving multiple hearings in backlogged courts. “I don’t expect there will be very many instantaneous removals.”

But it’s likely that Congress will be the next recourse. It’s not the first time these issues have bubbled up, but immigration officials worked with Congress years ago to put these protections in place for military members and their families.

“And the agency basically came to Congress and said, ‘We’ll fix this,' " Stock said. "And they did. They fixed it. They came up with these administrative policies and everything, so Congress never had to pass any laws to fix things.”

Rather than policy, programs like deferred action and parole in place could become statutory laws.

“The focus is now going to be on Congress to pass the laws, because the administration can’t be trusted to do things administratively,” she said.

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.