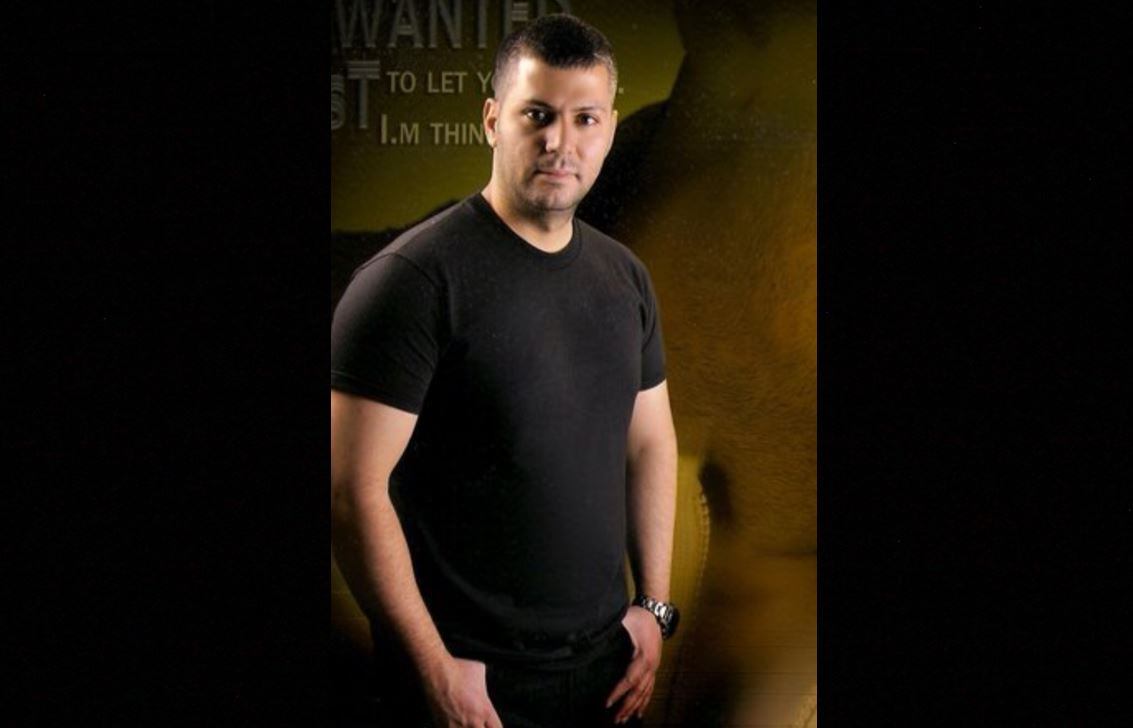

Dhurgham Abdulkareem spent two years as an interpreter for U.S. troops in Iraq, risking his own life on raids with the Americans, helping to capture insurgents and providing key advice for coalition forces, according to the reconnaissance troop commander he worked under.

The 41-year-old was a translator for 7th Calvary Regiment, among other units, from March 2009 through May 2011, according to U.S. Army documents and Defense Department IDs provided to Military Times.

The area of Baghdad they were in was home to many Islamic extremist groups, Abdulkareem said. “They were fighting each other, and sometimes they were hitting us.”

The job allowed Abdulkareem to help the U.S., he said, but it put him in a perilous position. Extremists in Iraq would now consider him a turncoat, a spy for the Americans.

But after obtaining a Special Immigration Visa, given to Iraqis and Afghans who help U.S. forces, it looked like Abdulkareem would be safe in a new country. Then he began the citizenship process.

Abdulkareem participated in a year of interviews and background checks, in addition to the intense screening that allowed him to work with U.S. forces in combat and obtain a visa to first come to Florida in 2012. Finally, he thought he was going to become a citizen on April 5.

He was told by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services to appear at a Naturalization Oath Ceremony to complete the process. It was going to be a life-changing event.

When he got there, however, he was told something had come up and he would not become a citizen that day.

“I was angry and afraid," Abdulkareem said of being pulled from the ceremony. “I didn’t lie about anything.”

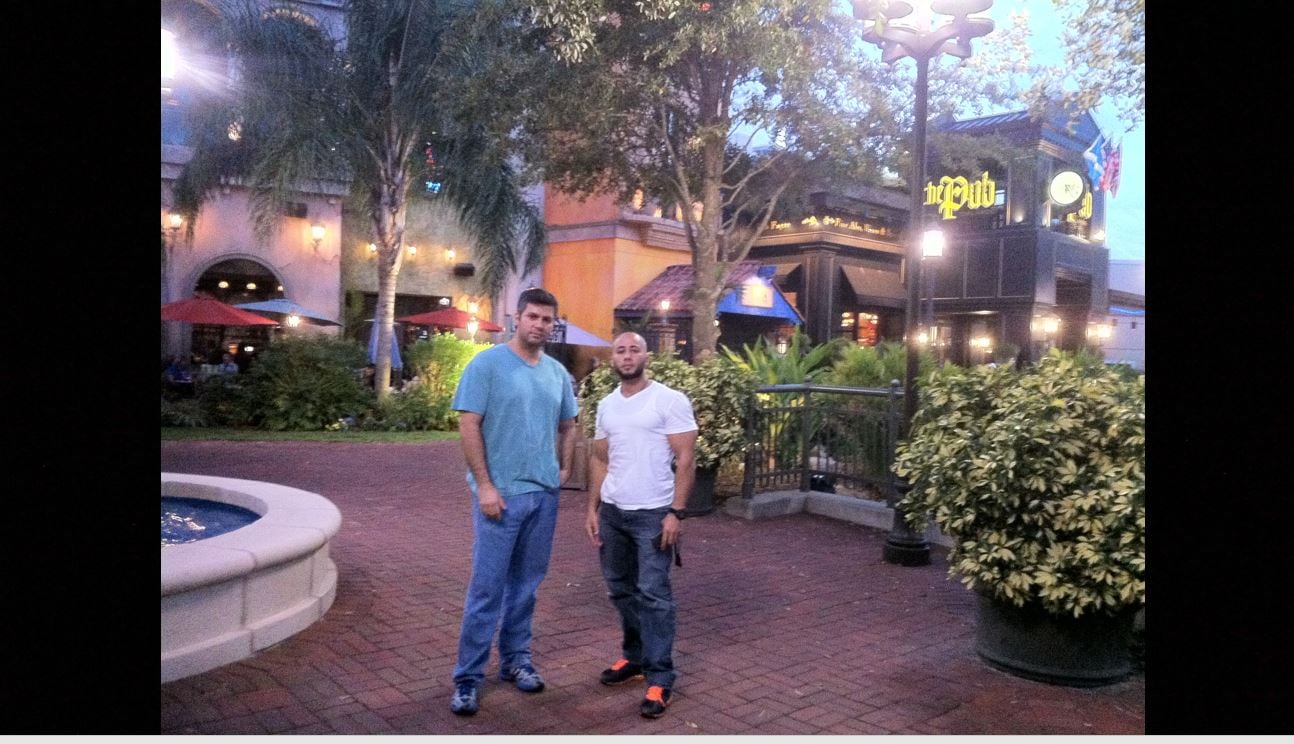

Immigration officials told him that one of the conditions of the immigration process was not yet finished, but they couldn’t tell him which condition that was. Abdulkareem had an idea, though. This same situation happened to his friend, Haeder Alanbki, another former interpreter for U.S. troops in Iraq who helped Abdulkareem adjust to life in America in 2012.

“I am not a naive person,” Abdulkareem said. “I know what is happening, and I’ve seen a lot of people with this happen to them. ... This happened to Haeder step-by-step.”

‘National security concerns’

To even come to the U.S., translators must first earn a coveted Special Immigration Visa.

The SIV program for Iraqis stopped accepting new applicants in 2014, but a backlog of almost 60,000 U.S.-affiliated Iraqis seeking to come to America exists, according to the nonprofit Human Rights First. An October 2017 executive order by President Donald Trump and its accompanying “enhanced vetting procedures” has further disrupted the processing of those applicants, the nonprofit alleges.

To become a citizen, the U.S. government’s secretive Controlled Application Review and Resolution Program, or CARRP, is allegedly a second obstacle, and the one that Abdulkareem and Alanbki think they hit.

CARRP is the subject of a class-action lawsuit filed by the ACLU and its affiliates. The plaintiffs say it has denied or delayed thousands of law-abiding people, many from Muslim-majority countries, from becoming citizens due to unspecified “national security concerns.”

It was started under the George W. Bush administration, and was continued during President Barack Obama’s tenure. The ACLU alleged in 2017 that the Trump administration’s “extreme vetting” policy dramatically expands CARRP.

The program is very opaque, and applicants typically do not know whether they’ve been subject to its scrutiny, said Sameer Ahmed, an attorney at the ACLU of Southern California.

Haeder Alanbki filed a lawsuit in 2018 alleging that CARRP erroneously listed him as a national security threat.

Alanbki thinks Abdulkareem may have been blacklisted by the same mechanism.

Military Times contacted immigration officials in Florida and Washington, D.C., on April 16. The next day, Abdulkareem was finally called and told he would undergo another interview in about a week.

Abdulkareem has no criminal convictions, according to court records. He received two civil traffic citations in Seminole County in 2016, both of which were resolved. But getting placed on CARRP is allegedly easy for non-citizens.

CARRP automatically applies to anyone whose name is on the government’s Terrorist Watchlist, but the guidelines for including people are “vague and over broad,” according to the ACLU. The civil rights advocacy group alleges that simply being “associated” with someone already on the watchlist is enough to get a non-citizen included.

The nature of a translator’s job could be a complicating factor during citizenship applications, said Betsy Fisher, policy director of the International Refugee Assistance Project.

“Translators, frequently, as part of their job, are asked to deal directly with militants to negotiate ceasefires or do any kind of interactions,” Fisher said. “Those are the kind of interactions that made interpreters so essential, but in many cases lead to additional security checks because they’re under suspicion for interacting with militants.”

A USCIS spokesperson would not comment on Abdulkareem’s specific case, citing privacy restrictions, but said that “some applications take longer than others to process" and “all individuals are notified in writing as to the outcome of their determination.”

Alanbki said the same situation happened to him. After serving as an Iraqi interpreter, he came to the U.S. on a Special Immigration Visa. Alanbki then joined the Florida Army National Guard as an infantryman. That should have made becoming a citizen even easier, he said.

But when he went to his Naturalization Oath Ceremony, he was pulled aside and told that he couldn’t take part. No reason was given.

“I shouldn’t have been accepted into the Army if I have something on my background,” he said. After filing a lawsuit and bringing his story to the Tampa Bay Times, Alanbki was finally made a citizen.

“That shows how hard it is to become a citizen,” Alanbki, who was shot and stabbed by al-Qaida insurgents while serving with U.S. troops in Fallujah, said. “It took two years ... more than $5,000 for the lawyers, plus all the emotion I went through with my kids.”

Alanbki applied for his oldest child’s citizenship last November. “Right now, I haven’t received nothing. ... He’s been in this country since he was eight months old. He’s almost nine" years old.

Abdulkareem requested Florida Sen. Marco Rubio to make an inquiry into his case, but he can’t afford a lawyer. Rubio’s office declined to comment due to Privacy Act concerns.

He currently works as a delivery driver near Orlando, Florida. While he has received interest from head hunters to work as an interpreter for Defense Department contracts, he needs to obtain citizenship to begin the security clearance process, the recruiter for the position told Military Times.

But after all the background checks and interviews interpreters go through just to work alongside U.S. troops in war zones, he hoped it would be easier. After all, he can’t go back home.

A spy in a maze

“I didn’t plan to originally come to the United States. I’m a musician. I play piano," Abdulkareem said. “I didn’t plan to even work with the U.S. Army, but I thought this would benefit everyone.”

Abdulkareem has a bachelors degree in fine arts from Baghdad University. He was teaching some classes there when he began working for the Americans. He hoped he could make a little bit of money while using his education, which included the ability to speak a dozen Arabic dialects, to ease the intense sectarian division in Iraq at the time.

“I started liking the job," he said. But the job did not win him any friends.

Insurgents viewed interpreters like Abdulkareem as “the people who tried to challenge them," he said. “We are like a spy there.”

To arrive at and leave Camp Taji, where he worked with Americans, he “tried to go in a maze” to hide his movements and prevent his family and home from being targeted.

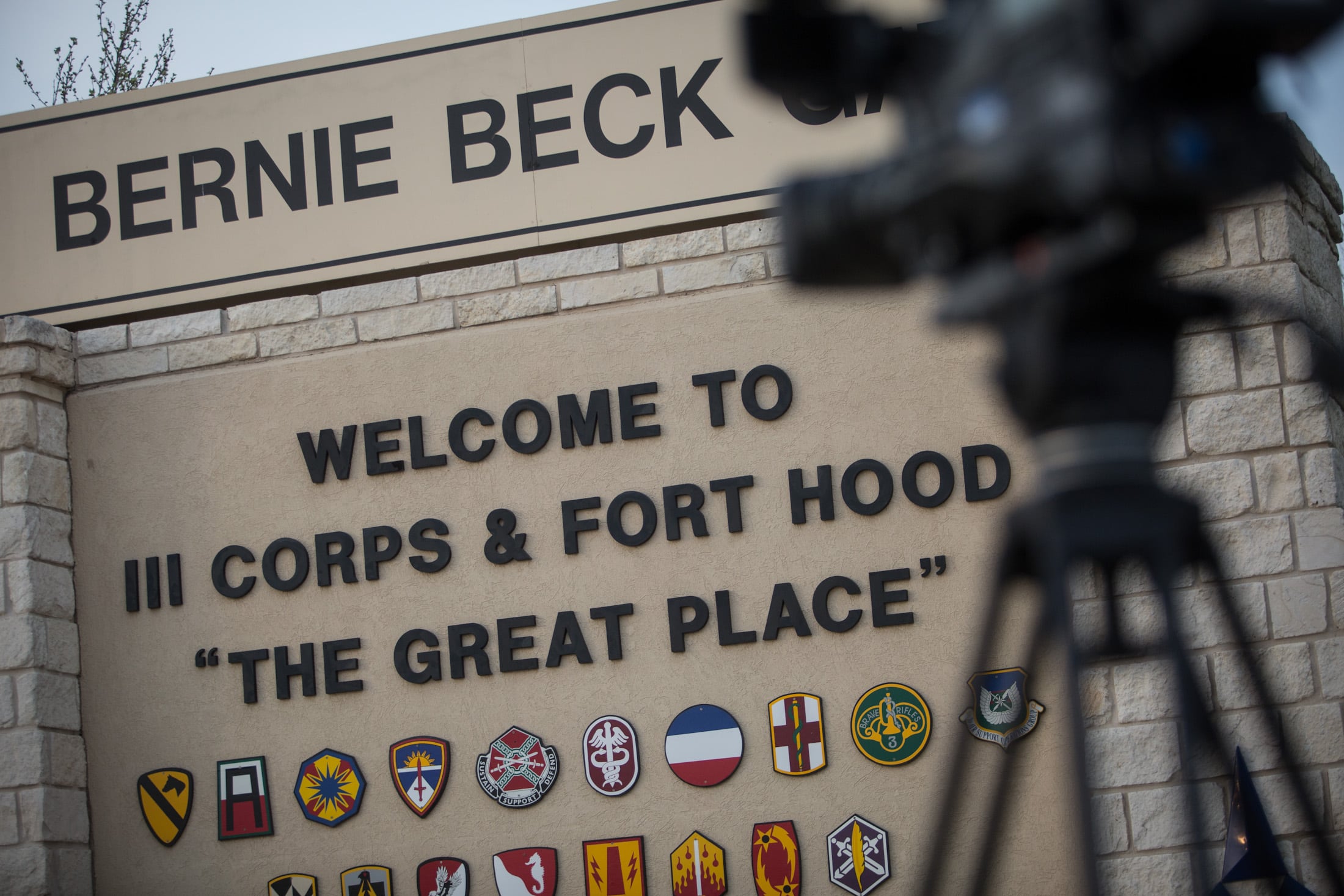

During his time working with U.S. forces, Abdulkareem spent many days and nights working with Blackhawk Troop from 1st Squadron, 7th Calvary Regiment.

“[Abdulkareem] was critical in helping my troop target and capture many [sectarian] extremist elements of Hussanyiah, a city in the northeastern periphery of Baghdad,” U.S. Army Capt. John Dolan wrote in a letter on Abdulkareem’s behalf during the immigration process.

Abdulkareem said he participated in about 40 raids with U.S. troops. As an interpreter, he had to be unarmed, but Dolan wrote that Abdulkareem “displayed the same level of bravery and dedication to our mission in Iraq that I see in my own soldiers."

“Like my soldiers, [Abdulkareem] has served the United States and its interests loyally and honorably, something that should never be forgotten,” U.S. Army 2nd. Lt. Gregory Moore said in a memorandum for the State Department to help Abdulkareem obtain a Special Immigration Visa in December 2009.

Abdulkareem obtained that visa in the summer of 2012 and came to Florida.

“It was so nice. It was raining a lot,” he said. "You start feeling safe. No one is going to hurt you or ask which sect of Muslim you are.”

Abdulkareem, who is divorced, hopes that once he attains citizenship, he can work to bring his daughter over, at least to visit. Currently, his ex-wife has custody of the child in Iraq.

He said he went back in 2015, the only time since coming to the U.S. That was to visit his sick mother, who has since passed away. Even that trip was risky, Abdulkareem said. He wouldn’t feel safe living there permanently and the only former Iraqis interpreters who choose to do so are too old to uproot their lives, he added.

Arriving in Florida reminded Abdulkareem of the years he spent in Kuwait in the 1980s as a young child.

“It’s kind of similar. It’s like a luxury area," he said. “Except in Kuwait, anyone can kick you out. In the U.S., everyone has the same rights.”

Abdulkareem liked that about working with U.S. troops, as well. There was an underlying promise of equality.

“Even when I was in the camp of the U.S. Army everyone eats the same food: the specialist, the major and me,” Abdulkareem said.

“That’s the magnificent thing that you don’t find in a lot of places," he added. “You feel that you have 100 percent of your rights. ... In other countries, you’re not going to find that.”

Kyle Rempfer was an editor and reporter who has covered combat operations, criminal cases, foreign military assistance and training accidents. Before entering journalism, Kyle served in U.S. Air Force Special Tactics and deployed in 2014 to Paktika Province, Afghanistan, and Baghdad, Iraq.