The Pentagon’s decision not to take action to protect military families from decades of exposure to cancer-causing chemicals until a 2016 Environmental Protection Agency warning did not sit well with members of Congress, who questioned Defense Department leadership on the issue at a hearing Wednesday.

“To put it charitably: it is unclear why DoD feels justified in passing the buck to the EPA," said House Oversight and Reform subcommittee on the environment chairman Rep. Harley Rouda, D-Calif. “Particularly in light of evidence suggesting DoD’s awareness of the toxicity of the chemicals since the early 1980s.”

RELATED

Rouda and ranking member James Comer, R-Ky., heard testimony from EPA Assistant Administrator for Water Dave Ross and Maureen Sullivan, deputy assistant secretary of defense for environment.

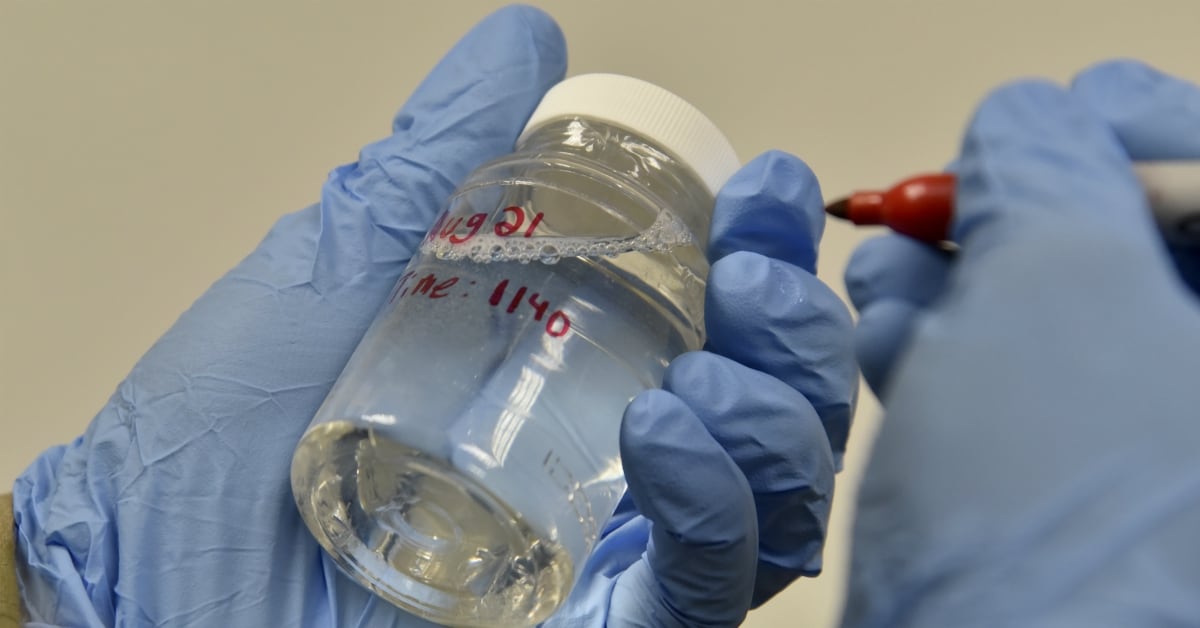

The perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl chemical compounds in question are found in everyday household items, but they were concentrated in firefighting foam the military used until just last year.

But at least one other DoD installation, Fort Carson in Colorado, use of the chemicals was stopped in 1991 after an Army Corps of Engineers study looked at harmful chemicals at its installations.

“Aqueous film forming foam (AFFF) is considered a hazardous material in a number of states,” the 1991 study, which was obtained by Military Times, read. “Firefighting operations that use AFFF must be replaced with nonhazardous substitutes.”

DoD has previously said that until the 2016 guidance from EPA on recommended exposure level limits, it did not know the severity of its exposure problem, which spurred it voluntarily providing filters and shutting some water sources, EPA’s guidance is not enforceable.

In March 2018, at the direction of Congress, DoD published its first-ever assessment of each contaminated base where the compounds had been found in either on-base or off-base water sources. More than 126 locations were identified — some with exposure levels hundreds of times greater than EPA’s 70 parts per trillion recommendation.

Since the release of the list, scores of families and veterans have contacted Military Times with stories of families or neighbors with cancer, or children with birth defects. Hope Martindell Grosse, who attended Wednesday’s hearing, is one of them.

Grosse grew up in a neighborhood that was across the street from the firefighting training center at Naval Air Warfare Center Warminster, in Pennsylvania.

Her family and others in the neighborhood relied on their private well for water. Now, not only that well, but a public water well installed in the late 1990s is shut down — with remaining levels of PFAS at more than 1200 parts per trillion.

Her father died in 1990 at age 52, from cancer. Three months later, at age 25, Grosse was diagnosed with cancer as well. She has successfully fought it since, but “anytime something is wrong with my health — just about anything — I am immediately filled with a crippling fear that it is cancer,” she said in testimony submitted for the hearing.

Tara Copp is a Pentagon correspondent for the Associated Press. She was previously Pentagon bureau chief for Sightline Media Group.