The United States began flexing its overseas muscles at the outset of the 20th Century — slowly at first, and later with more regularity and greater impact.

In doing so, the country enmeshed itself in several smaller conflicts that not only combatted colonialist powers but delivered distinct advantages to the young nation. There was the Spanish-American War, the Philippine-American War, the Boxer Rebellion and a series of fights known as the Banana Wars.

Each advanced U.S. political and economic interests. And in most cases, the Marine Corps led the charge. At the helm of nearly all those fights was one particular Leatherneck, Smedley Butler.

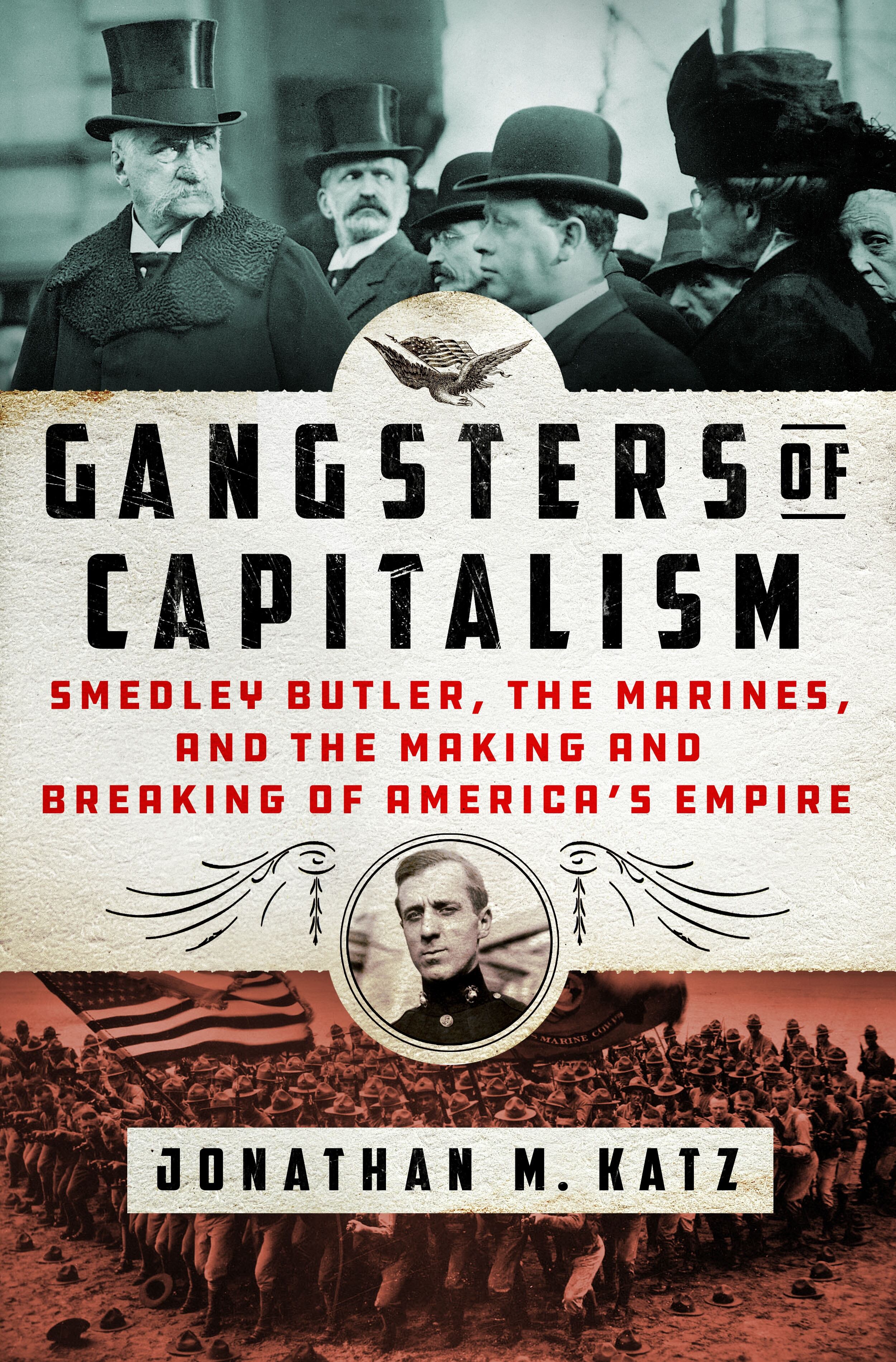

Butler serves as the window through which author Jonathan M. Katz views America, the Marine Corps and the convergence of business and war in his newest book, “Gangsters of Capitalism.”

Butler served from 1898 to 1931, ultimately achieving the rank of major general. During that span, he saw more war in more places than perhaps any Marine before him and most since. He began as a near-crusader for the American cause, known as “The Fighting Quaker” as one who delivered democracy to the world’s downtrodden.

Over the course of his career, Butler would receive two Medals of Honor, first for his actions in Veracruz, Mexico, and later for fighting in Haiti.

But the starry-eyed optimism of “Old Gimlet Eye” dwindled as he began to recognize corporate interests intertwined with the fighting and the dying of his Marines. Some of those very corporate leaders would later approach Butler in retirement, seeking his leadership in a coup — this time not in some shaky backwater, but in the United States.

What became known as “The Business Plot,” a scheme by industrialists threatened by then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Depression-busting “New Deal,” forced Butler to speak out. He published a slim volume, the renowned “War is a Racket,” which outlined how corporate interests married to military might spell doom for the American dream of a free globe.

That book presaged the final message, decades later, of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who warned the nation in 1961 of the dangers of the “military-industrial complex,” echoing the concerns Butler had penned approximately 25 years earlier.

Katz spoke with Marine Corps Times about his discovery of Butler, what led him to delve into this nearly forgotten chapter of history and what lessons this period holds for today.

*Editor’s Note: This author Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.

MCT: What led you to this particular topic?

KATZ: I was working as an Associated Press correspondent in Haiti, reading its history. That led to my first book, “The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster.” Through researching that work I traced interventions and corruption that plagued the country going decades back.

The Marines invaded and occupied Haiti in 1915. This occupation came directly from bankers influencing President Woodrow Wilson to control the island nation to protect their interests. The occupation didn’t end until Roosevelt ended it in 1934, when the last Marines left the island.

How did Butler become a central figure in your research and writing?

I don’t remember if it was the first dip into the material that I found “The Business Plot” and “War is a Racket” or not, but I was just blown away. I mean, I couldn’t figure out how this Marine, who is known in Haiti as being one of the worst occupiers, ends up writing an anti-war tract later in his life.

In fact, my first assumption was this must be a different guy. Maybe it was his son or something, but it couldn’t possibly be the same man. And then I saw where Butler had been involved in nearly all the U.S. interventions of the period. I realized Butler’s story was the story of American empire.

Did Butler march on as the good soldier throughout his time in these campaigns? When did he come to some of these realizations?

Butler was critical [and] showed a capability of self-criticism. And he was not afraid to rock the boat in his little corner of the Marine Corps. But until Nicaragua it had been much of, say, suggesting to his commanding officer that we shouldn’t do it this way.

Nicaragua was an extremely aggressive, extremely overt war of colonialization and annexation. It was pretty dark, with rhetoric about “benevolent assimilation” from President William McKinley at the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898. And Butler also saw in the Philippines a large gulf between what American leaders were saying and what troops were doing on the ground.

What evidence did you find in your research that reflects some of these realizations?

While in Nicaragua, Butler starts portraying the situation in letters back home to his parents. He’s having conversations with wealthy Nicaraguan elites, who are very open about wanting Americans to do certain things that will give their families an advantage. [But] this doesn’t keep him from doing anything. He continues, and in many ways, many of his most egregious acts he commits are as a Marine.

But it’s in these personal letters you start seeing a little more awareness of what’s going on. He’s not alone in his acts; there were other American officers in Nicaragua and it was very obvious to everybody involved what was going on and who was calling the shots.

Why is this period important for the Marine Corps and its relationship to U.S. interventions?

This is an inflection point in Marine Corps history. Until that point it had been mostly a naval infantry — guarding ships, guarding ports — but through these wars many Marines get their first taste of combat. Based on research, it appears one in three Marines at the time passed through Veracruz, Mexico. Marines were everywhere during this period — Haiti, Nicaragua, Mexico, China, the Philippines.

What makes Butler unique is not just that he’s everywhere — because a lot of his comrades were everywhere — it’s that he has so much to say about it. He’s a prolific letter writer and his family saves the letters.

You took the time to travel to the locations of most of the major battles and wars and interview people living there today. Why was that important?

It’s a book about historical memory. Things that are remembered or forgotten and the active process of suppression or omission. I really wanted to find the ways in which these moments, these wars, interventions, invasions and occupations are remembered in the country where they happened.

I also wanted to get at multiple angles. I wanted to know, at every point along the way, the thoughts of the enlisted, officers, politicians, Americans and locals. At no point am I saying one memory is more accurate. I was really trying to go deep into these chains of memory, the way that history is contested and handed down and the work these memories do in some places and not others.

What from this period or the legacy of Butler resonates in the Marine Corps today?

It has come down to a sort of official line in today’s Marine Corps that Dan Daly and Smedley Butler both earned two Medals of Honor. But in some cases, I’ve seen deployed Marines sharing copies of “War is a Racket.” There’s both an official Marine Corps line and more of an underground current that has been kept alive by some Marines.

Late in the Vietnam War, there was some rediscovery by Marines of Butler’s anti-war voice. Marine Commandant Gen. David Shoup served as a young officer in Shanghai, protecting American interests from local national rebellion against foreigners in 1927. In the early stages of the escalation in Vietnam, Shoup was one of the few general officers who was very outspoken against President Lyndon Johnson’s policies. He treasured Butler.

A similar thing happened among Marines in the waning years of Iraq and Afghanistan. Butler fits into a kind of Marine Corps cultural conception of itself as a maverick force. The part of the military that is more likely to be self-critical or critical of the policies it carries out. I think Butler played such a fundamental role in creating the image of the Marine that survives to this day.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.

Tags:

smedley butlerGangsters of capitalismbooks on marine legendsmarine corps medal of honor winnersmarine medal of honor recipientswhich marines won two medals of honorbanana warsmarines in latin americamarines in boxer rebellionmilitary industrial complexthe business plotwar profiteeringbusiness and waru.s. empirejonathan m. katzwar is a racketthe racketIn Other News