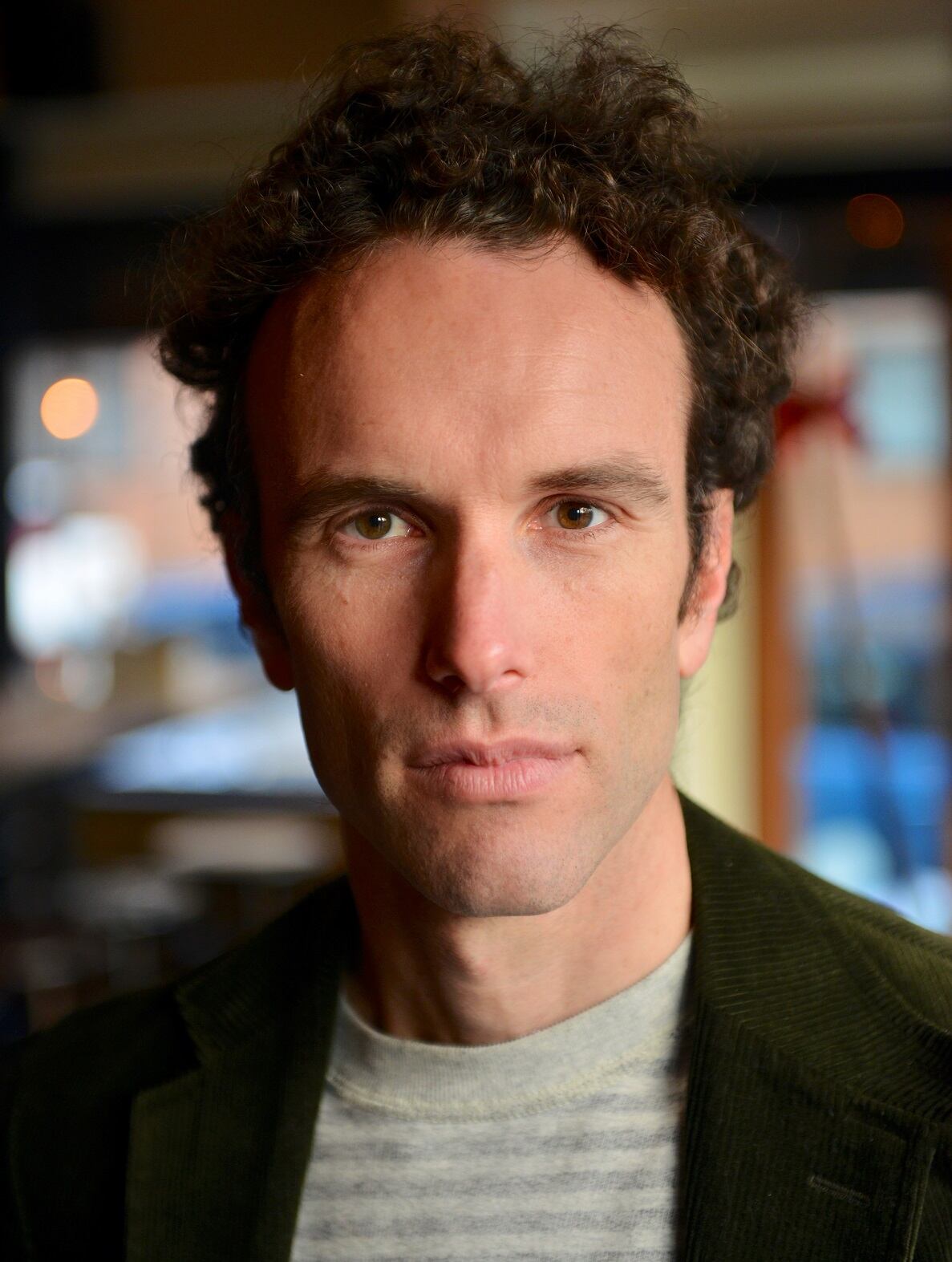

August 2021 found Marine veteran Elliot Ackerman uncomfortably in two places at once.

Physically, the decorated former Marine Raider was on vacation in Rome with his wife and young sons, his schedule filled with sightseeing tours and dinners with friends.

Emotionally and mentally, he was on his last high-stakes mission in Afghanistan, using encrypted chats and his deep network to help a group of former U.S. interpreters make it past a battery of checkpoints and to the promise of safety and escape at Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul.

A decade out of uniform, Ackerman ― like many veterans and others with ties to Afghanistan ― forwent sleep and plumbed his own resources to help these U.S. allies flee the country simply because no one else was likely to do so.

“It’s almost like your mind is being cleaved in two, where you’re watching your child play and have the best day ever at a swimming pool, all this stuff that is lovely in life,” Ackerman told Marine Corps Times.

“And then on your phone, there are people desperately hoping you will help them, watching their lives vanish, and you’re watching them at the same time. That becomes such a schizophrenic existence. And I would wager it’s one that anyone who has kind of dipped their toes in these wars, and particularly has seen how Afghanistan has ended, has experienced.”

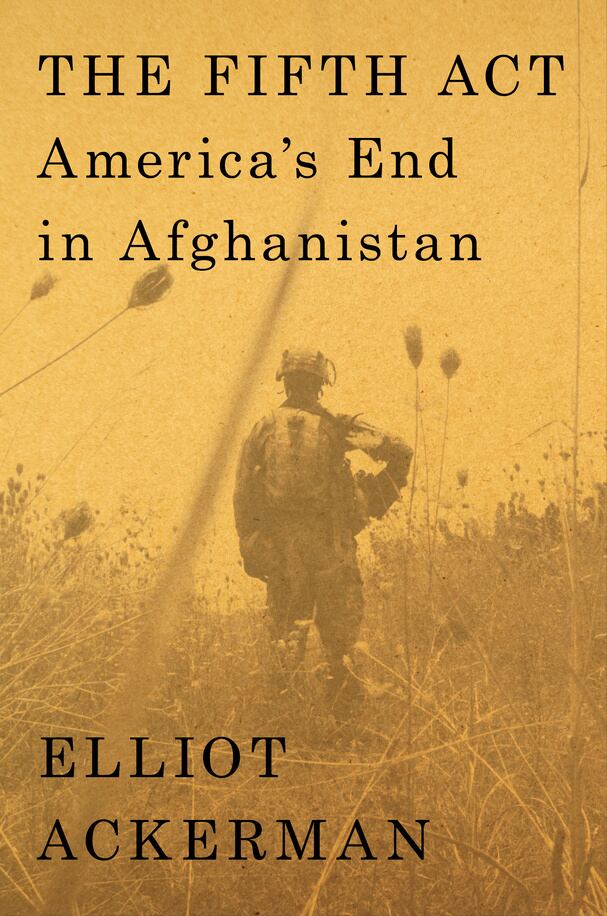

Ackerman takes the reader with him into the intensity and anguish of witnessing this collapse in “The Fifth Act: America’s End in Afghanistan.”

The book toggles between 2021 and scenes from his past involvement in the war, as a leader of Marines and later a CIA adviser.

Like Ackerman’s attentions in Rome, the book’s focus is split: it’s part memoir, part lament, part warning about where the nation finds itself at the dissociative conclusion of a dissociative war. At every turn, though, it’s intensely personal.

In a particularly poignant story, from a deployment near Shewan in Afghanistan’s Farah province in 2008, Ackerman faces a wrenching decision about what risks to take in recovering a fallen Marine.

“When you live with a war ― as you would a person ― for so long, you come to know it on intimate terms, and it comes to change you in similarly intimate ways,” Ackerman writes.

Ackerman spoke with Marine Corps Times ahead of his book’s Aug. 9 release. The following Q&A has been lightly edited for brevity and clarity.

Q: Is there a historical analogy that comes to mind for the way veterans like you have taken the initiative to rescue Afghan allies and their families in the absence of comprehensive action from the U.S. government?

A: The one obvious historical analogy, which has already been mentioned before, is, the [1940] Dunkirk evacuation. And I think that in the very intense days of August of last year, when this was going on, that seemed like an apt parallel.

But you know, as time draws on, and the world’s attention moves to places like Ukraine, it seems as though we’ve now transitioned into a vigil that looks more like the POW/MIA effort at the end of Vietnam.

We have a huge number of Afghan allies who we are still connected with. All the people who were touched by 20 years of war and have strong and deep relationships with Afghans ― they’re not just gonna let it go.

Q: As we approach the one-year anniversary of the U.S. departure from Afghanistan, what words do you use to describe that time, looking back?

A: The single word that I have settled on is “collapse.”

It was a collapse of American morals: no man behind is deeply ingrained in America’s military ethos.

When we asked all of our veterans, 20 years’ worth of veterans in many cases, to leave all these people behind, it felt like sort of the final ask is going to be this enormous betrayal of that value. So that was a collapse of morality, American competence. It was a collapse of hierarchy.

I found myself in chat rooms and on phone calls with former four-star commanders who were just trying to get their interpreter out, which is pretty remarkable, and these are good people, but no one could do anything.

And then lastly, a collapse of time. Many of us who, you know, the war had ended for us, we had built lives away from the war, we’re now sucked right back into it.

Q: It was striking to me how Americans who had ignored the war for a long time began to care much more about it as Kabul fell. Do you think Americans understand anything about war now that they didn’t a year ago?

A: It’s a little disorienting. I equate it to the fact that I think Americans have a very strong moral compass, when called upon.

The vast majority of Americans across the political spectrum turned on their TV, saw what was happening, and just said, “This isn’t right.”

We also have a very short attention span. So those two are obviously in conversation with one another. But I think that Churchill said, “Americans will always do the right thing, once there’s nothing else left to do.”

Q: In your own words, what is the Fifth Act?

A: If you look at classic dramatic structures, tragedies are told in five acts. So it allowed me to try to put a framework over these 20 years, and a structure around Afghanistan.

The first act is Bush; the second act is Obama. The third act is Trump; the fourth act is Biden.

And then within that construct, there are five distinct cases of evacuations that I was involved in last summer. And then, I write about one of my own experiences fighting in Afghanistan in which I really had to grapple with this idea of, what does it mean to never leave anyone behind.

Q: At this point, what do you believe the U.S. could and should do to address the aftermath of our hasty exit from Afghanistan?

A: There’s legislation right now (The Afghan Adjustment Act) that would greatly facilitate Afghan immigrants to get their working visas and to stay in the country more easily and get on the pathway to citizenship.

If you look at previous generations of folks who have come to this country in the wake of wars, whether it’s the Second World War or Vietnam, I think that is not only the morally right thing to do; it’s in our best interest to do that.

Then there are larger questions when we look back at these 20 years of war, and how they were engineered with an all-volunteer military and how they were funded with deficit spending ― the result of that being the anaesthetization of the broader American public to our wars. I think it’s worth taking a look in the mirror and saying, maybe we citizens should be demanding for the health of our republic that, when we go to war, we do it in a way that everyone feels a little bit of the pain and everyone stays engaged.

And these are the issues that should be right in the front of our national consciousness. It’s morally wrong to take veterans and have them fill this gap.

There’s a bit of moral blackmail going on. Because if you weren’t involved in these wars, you don’t have people texting you, sitting there, sending you photos of their families, saying, “Please help us.” And you’re not being asked to either stop your life and figure out how to help these people, or shut off your phone and ignore them, and live with that on your conscience.

Let’s stop asking veterans to do that.

Q: In the last section of your book, you mention Marine Lt. Col. Stu Scheller, and describe his public denunciation of the Afghanistan exit ― and subsequent firing ― as an immolation, comparing him to the Tunisian fruit vendor who helped to trigger the Arab Spring.

Do you think there’s a lesson the country or the military failed to learn from Scheller’s actions?

A: I still wrestle with what to make of what Stu Scheller did. My conclusion is, we should all watch this space.

So many Americans, they don’t understand the military; there’s just no familiarity with the culture. Yet we have a massive military under arms. And we have extremely dysfunctional domestic politics.

And if you look back from Caesar’s Rome to Napoleon’s France, when you couple the massive standing military with dysfunctional politics, it doesn’t bode well for democracy.

Q: Do you feel this nation is too far gone?

A: I remain very bullish on America, because we have shown in moments of great dysfunction the ability to course correct.

What a remarkable year this has been; six months after the fall of Kabul, we also have what happens in Ukraine ― the response, and it was a short-lived response, was of a nature that I haven’t seen since the Sept. 11 attacks.

So it’s important to keep what happened in Afghanistan in conversation with what’s happening in the rest of the world and hope that the better angels of our nature will pull us through our present dysfunction.

Q: It is remarkable to me how veterans and others even now are going to great lengths to help our allies who remain in Afghanistan.

A: I think one of the big glimmers of hope is that when the U.S. government failed to appropriately respond, the American people did respond in a very big way.

And it’s important to highlight that the people who were involved in this evacuation were not just veterans.

This wasn’t just a niche issue, where veterans cared and nobody else cared. A lot of people cared, who had never worn a uniform, and they put their lives on hold and did everything they could to try to help. Most of them didn’t know the Afghans they were helping.

A lot of people I mentioned in the book who were making things happen, had tenuous connections to Afghanistan; they just decided they were going to help.

“The Fifth Act,” from Penguin Press, was published Aug. 9.