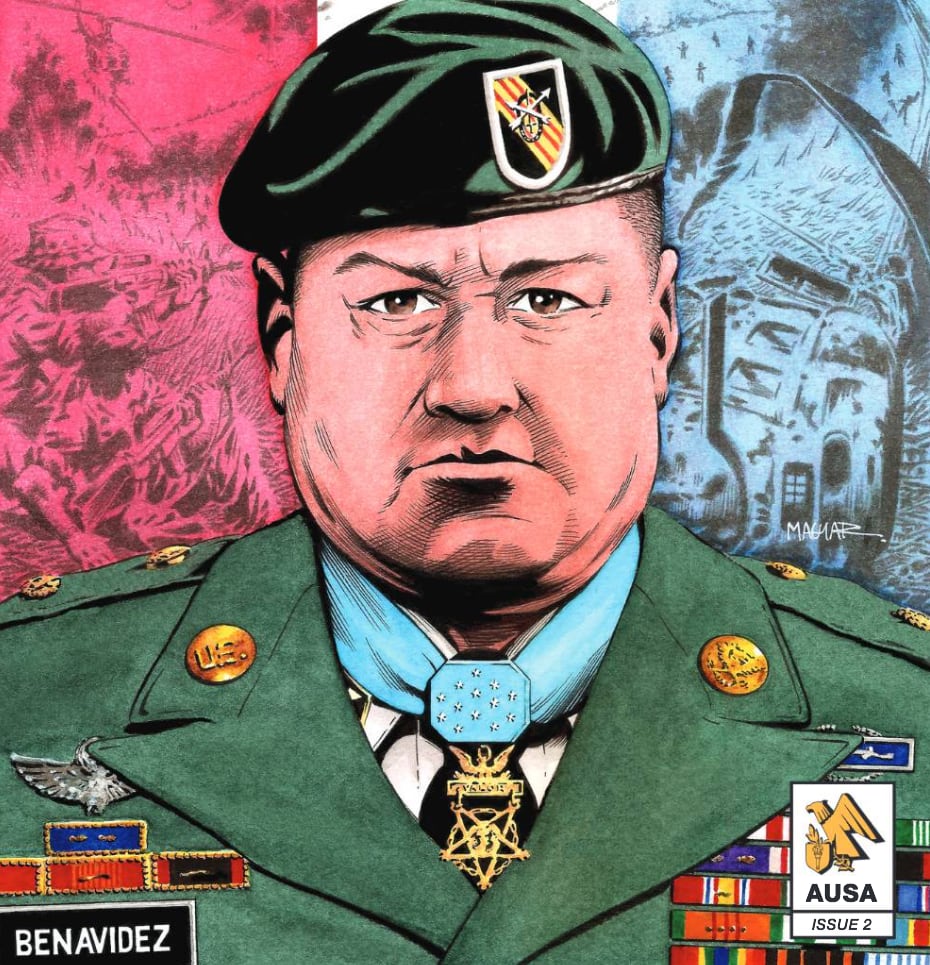

A new book detailing the life of Army Master Sgt. Roy Perez Benavidez examines the complicated legacy of a man who could trace his ancestry back to Texas before it was a state and who faced discrimination even after receiving the nation’s highest award for military valor.

William Sturkey, an associate history professor at the University of Pennsylvania, has focused much of his research and writing on marginalized communities. He found Benavidez’s story, one that bridged major racial shifts in the United States during the tumultuous 20th Century, as emblematic of the Latino community’s struggle for acceptance and success in America.

Sturkey’s book, “The Ballad of Roy Benavidez: The Life and Times of America’s Most Famous Hispanic War Hero,” published in June by Basic Books, dives into the Medal of Honor recipient’s life before, during and after his service and what Sturkey thinks it says about wider issues within marginalized populations.

RELATED

On May 2, 1968, Benavidez was serving with the 5th Special Forces Group in Vietnam when a 12-man reconnaissance team was inserted by helicopter along the Ho Chi Minh trail. Disaster struck almost immediately.

Shortly after they landed, the team was raked by heavy fire from North Vietnamese Army units. During the ambush, three helicopters attempted to reach the cut-off recon unit but were unable to.

Listening to the battle from a nearby post, Benavidez watched as the helicopters returned, and then immediately ran to jump aboard as they made another attempt to relieve the patrol. As his helicopter hovered, Benavidez leaped to the ground and ran 75 meters under heavy fire to reach the team. As he did so, he was struck by enemy fire and shrapnel in his right leg, face and head.

Once he reached the team, he found that nearly all of them were wounded, and others were dead. Despite his injuries, Benavidez took command of the survivors. Throwing smoke canisters to identify their position to friendly forces, he dragged and carried half of the wounded to an incoming medevac chopper himself. As the wounded were loaded aboard, Benavidez moved to retrieve the body of the team’s leader, who had been killed. As he did, the helicopter’s pilot was struck by incoming fire and killed, and the aircraft crashed.

Once again, Benavidez raced to where he was needed and began pulling the wounded from the wreck. He then called in tactical airstrikes and was wounded again. Throughout it all, he continued to fight for his men until another helicopter finally arrived and extracted the team. For his actions that day, Benavidez was awarded the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest award for valor, on Feb. 24, 1981.

Sturkey spoke with Army Times about his own background with veterans and other marginalized communities and Benavidez’s story.

This Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Can you tell readers a little bit about your background and interest in the military?

A: I come from a place just outside Erie, Pennsylvania, which has a lot of working class young men and women who join the military. I graduated high school in 2000. Although I didn’t serve, I was part of the War on Terror generation. There were military recruiters in our high school all the time. This book is dedicated to my friend Army Spc. Donald S. Oaks Jr., who died on April 3, 2003, while serving during Operation Iraqi Freedom. I think because of that I always really pay attention to veterans’ issues.

Q: How did you come across Master Sgt. Roy Benavidez’s story and decide to write about it?

A: As a historian, I’ve always been interested in stories of marginalized people, especially working classes of color. They don’t always get the same treatment in American history as politicians and celebrities do. It was about 2005 to 2006. I was really wrestling with some of the experiences my friends in the military were having, some of their deaths both in combat and after they came home. I was thinking about what our society does when it comes to veterans. I heard about Roy’s story and how very soon after he received the Medal of Honor, he lost his social security disability benefits. It made me think: how do we balance the celebration of veterans versus how do we treat veterans in terms of public policy?

Q: Could you tell us about the racial climate for Latino and Hispanic people during Benavidez’s lifetime and especially his service?

A: Historians have been telling each other for years that Vietnam was a “poor people’s war.” The data just doesn’t really bear that out. There were a lot of Hispanic and Black people killed. There was absolutely racism, some data shows their casualties were a little higher than you’d expect, so with Roy I looked more at who were his role models growing up. Born in 1935 in Texas, he grew up in a very, very racist society. He couldn’t go to the front of restaurants. He couldn’t sit in the front rows at movie theaters. But when he was growing up, Hispanic soldiers who’d served honorably in World War II were all around. But there was a famous story in Texas of a Hispanic Americanwho died after the war and his family wasn’t allowed to bury him in a white cemetery, even though he’d served his country. So, Roy’s generation was the first generation who got to build off the legacy of those World War II soldiers. The military was an opportunity to succeed, and he would say there was more racial equality in the military because of the command structure and the urgency of the Vietnam War.

Q: Would you share how his Medal of Honor award finally came and his life after the Army?

A: Roy’s actions took place in 1968 and he didn’t receive the medal until 1981. In the early to mid-1970s there was a lot of Vietnam War fatigue among the U.S. population. People were just sick of talking about it, certainly nobody in the military wanted to talk about it. But by the early 1980s some of that attitude had relaxed. Movies such as “Apocalypse Now” and “Deer Hunter” were now being replaced by “Rambo” and later “Top Gun.” There was more of an attitude of celebrating the military. It was a challenge because there were few witnesses to his actions. After many rejections, Roy and others finally found a survivor from the mission who could provide vital testimony to what happened that day and they were ultimately successful in getting his actions recognized. For many years he was the most recent living recipient of the Medal of Honor. Even with the 1993 Battle of Mogadishu, the two soldiers received it posthumously. But in 1983 he told the media that his Social Security disability benefits and benefits for veterans were going to be cut and he testified to Congress to stop the cuts. Because he was the most recent living recipient he was involved in many veterans issues, called upon by political leaders and military groups to give speeches. He died in 1998.

Q: What was something surprising you discovered in your research?

A: Because Roy and his family were Hispanic, they often suffered discrimination and were seen as second-class citizens. But his family traced its continuous lineage back to Mexican settlers in Texas before it was part of the United States. His family fought alongside other Texans for their independence from Mexico. One of his relatives, Plácido Benavides, was known as the “Paul Revere of Texas” during the Texas Revolution. Benavides helped revolutionaries take San Antonio and was later in a unit ambushed by the Mexican Army near San Patricio. During the battle he was dispatched to Goliad to alert troops there of the Mexican Army’s approach. Despite this history, his family had to flee to Louisiana to avoid racist mob violence. When they returned to Texas, they discovered that white settlers had moved onto their land and claimed it for themselves.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.