WASHINGTON — The command rolling out the Army’s new, all-encompassing fitness program has a fresh way to get the program’s expertise inside more units.

If an active duty division commander can dedicate a five-soldier team — comprised of one captain, two senior noncommissioned officers and two junior NCOs — to learning the essentials, the Center for Initial Military Training under Training and Doctrine Command will send cadre to them.

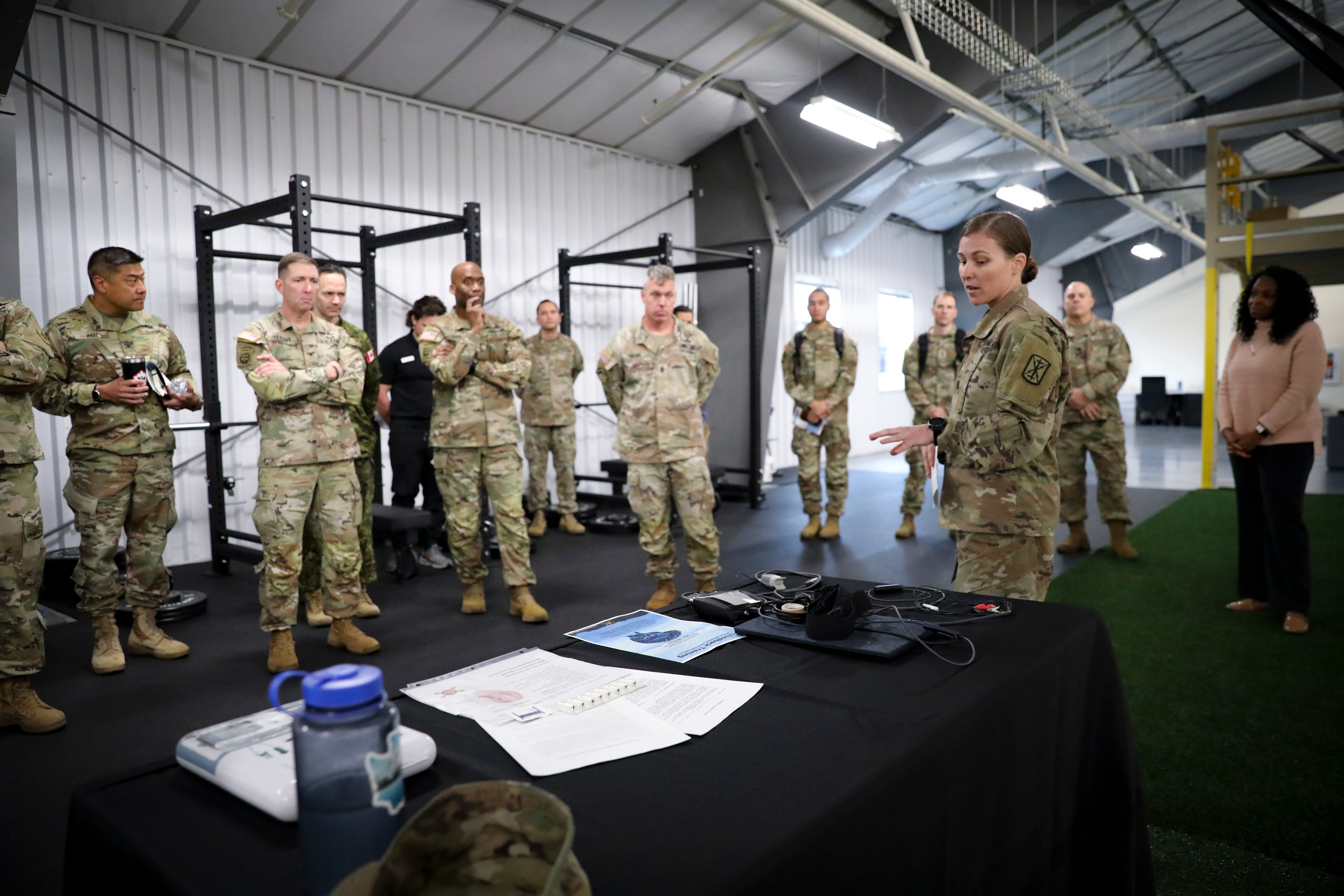

That’s the newest approach to filling ranks across the Army with the practices of Holistic Health and Fitness as the service pushes equipment and training staff to 110 active duty brigades.

Army Chief of Staff Gen. Randy George announced in September at Fort Moore, Georgia, that he will seek to double funding for the program and bump up the annual brigade goal from 10 to 15.

It’s no small effort. The chief noted it will be the largest personnel contract in Training and Doctrine Command history, hiring 1,041 strength coaches and 413 athletic trainers, among other staff.

Maj. Gen. John Kline spoke with Army Times ahead of the Association of the U.S. Army’s annual conference to share updates on the program and what’s headed to soldiers in the coming months. Developments include:

- H2F will now oversee the Army’s Pregnancy Postpartum Physical Training program, also known as P3T.

- The Army Physical Fitness School has been renamed the Holistic Health and Fitness Academy.

- A 12-week special qualification identifier course in H2F is awaiting approval.

- A two-week online additional skill identifier course is awaiting approval.

- The Army selected CoachMePlus for data collection and tracking on a wearables pilot.

The five-soldier team concept, which builds so-called H2F integrators, is an effort to spread the knowledge into the formations, allowing those division teams to essentially train the trainer in their brigades and get H2F to units.

“If a division says they’re ready, I will put together a team if you’re ready to come out and train for it,” Kline said.

But the Center for Initial Military Training isn’t here to dictate how units implement the day-to-day use of H2F principles and training; brigades have their own missions and needs.

For instance, 10th Mountain Division in Fort Drum, New York, has a specific mission that involves mountain and cold weather work. The 25th Infantry Division in Hawaii must ready itself for jungle climates. They would need to train differently.

The H2F integrator approach is key because even at 15 brigades a year with a 110-brigade goal by 2029, that’s still only 47% of active duty brigades. This means more than half of the active duty Army and all the Guard and Reserve must have their soldiers trained to bring the program into the formation.

The full H2F staff includes two dozen contracted staff members. The team consists of an H2F program director, nutrition, injury control and mental health directors, a registered dietician, a physical therapist, athletic trainers, strength coaches, cognitive performance specialists, occupational therapists, and more.

For equipment, each brigade receives a deployable medical equipment set, deployable “gyms in a box,” garrison equipment sets and a Soldier Performance Readiness Center at garrison.

The P3T program has existed in the Army for years but has largely focused on physical training and was somewhat decentralized, said Col. Jason Faulkenberry, H2F program director at the Center for Initial Military Training.

Two full-time staffers are slated for hire to oversee P3T at the center. The command will emphasize sleep, nutrition and mental components for P3T participants in addition to the physical aspects.

The command will also update the website to include answers to common questions for P3T participants, as well as include guidelines for soldiers and H2F instructors overseeing P3T participants, Faulkenberry said.

The wearables pilot, which could begin in April or May with a brigade, will be more than handing out a bunch of smartwatches and telling soldiers to go for a run. Kline said educating the commands, leaders and soldiers on how to understand their own behaviors through data — health risks and all-around readiness, for example — will inform training plans and individual soldier choices across all H2F domains.

“For the soldier it helps them see themselves and understand themselves for change,” Kline said.

One recent example of a soldier using H2F is Staff Sgt. Ashley Buhl, who won the competition for drill sergeant of the year in September.

Kline noted that Buhl, a drill sergeant with the 193rd Infantry Brigade at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, worked with an H2F Team for 14 weeks to prepare for the competition. That work included a lot of planning, teaching soldiers how to time their training, and peak their performance for an assessment, competition or deployment.

For the command, Kline expects the wearables will help leaders understand how well H2F is working as well as assist with gauging soldier and formation readiness.

Soldiers will receive a wrist device, chest strap and ring device for sleep monitoring; cadre will receive tablet computers to monitor their soldier or unit dashboard. “It’s a high level of granularity they’ve never had before,” Kline said.

The individual information will be privacy protected, and aggregate data at various echelons will serve as a way for commanders to get a snapshot of readiness.

Currently, much of the data gathered on training or readiness measures lags by nearly six months before a commander can see what worked and what didn’t. If adopted across the Army, wearables could save time; share data, lessons learned and best practices; and fuel new approaches to various fitness domains.

For example, an H2F trainer could look at a wearables report, see that certain soldiers slept poorly, were dehydrated, or reported soreness or injuries. With the system in place, automated appointments with physical or occupational therapists could be an option.

That data could help decide to shift the training plan to fit where the soldiers are performing, whether that’s ramping up the intensity if well rested, or adjusting the exercises or duration if the formation looks injury prone.

Zooming out, the wearables — combined with data already collected — are expected to fuel the larger data ecosystem that H2F is building. That ecosystem will give commanders a wider and deeper view across the force.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.