ARLINGTON, Virginia – The top general for Army training and doctrine sees discipline and skill mastery as crucial to building trust, which in turn improves combat effectiveness.

The best way to build trust? Work in teams.

At today’s Association of the U.S. Army Coffee Series, Gen. Gary Brito, head of Training and Doctrine Command, told attendees that work from basic training to the combat training centers is intended to develop soldiers’ individual expertise and further hone those skills as they work as a team.

Association President retired Gen. Robert Brown, who moderated the talk, told the audience that observers have seen catastrophic battlefield mistakes emerge in the Russia-Ukraine War from distrust between leaders and their soldiers.

“Russians didn’t tell divisions or below what was going on because they didn’t trust them,” Brown said.

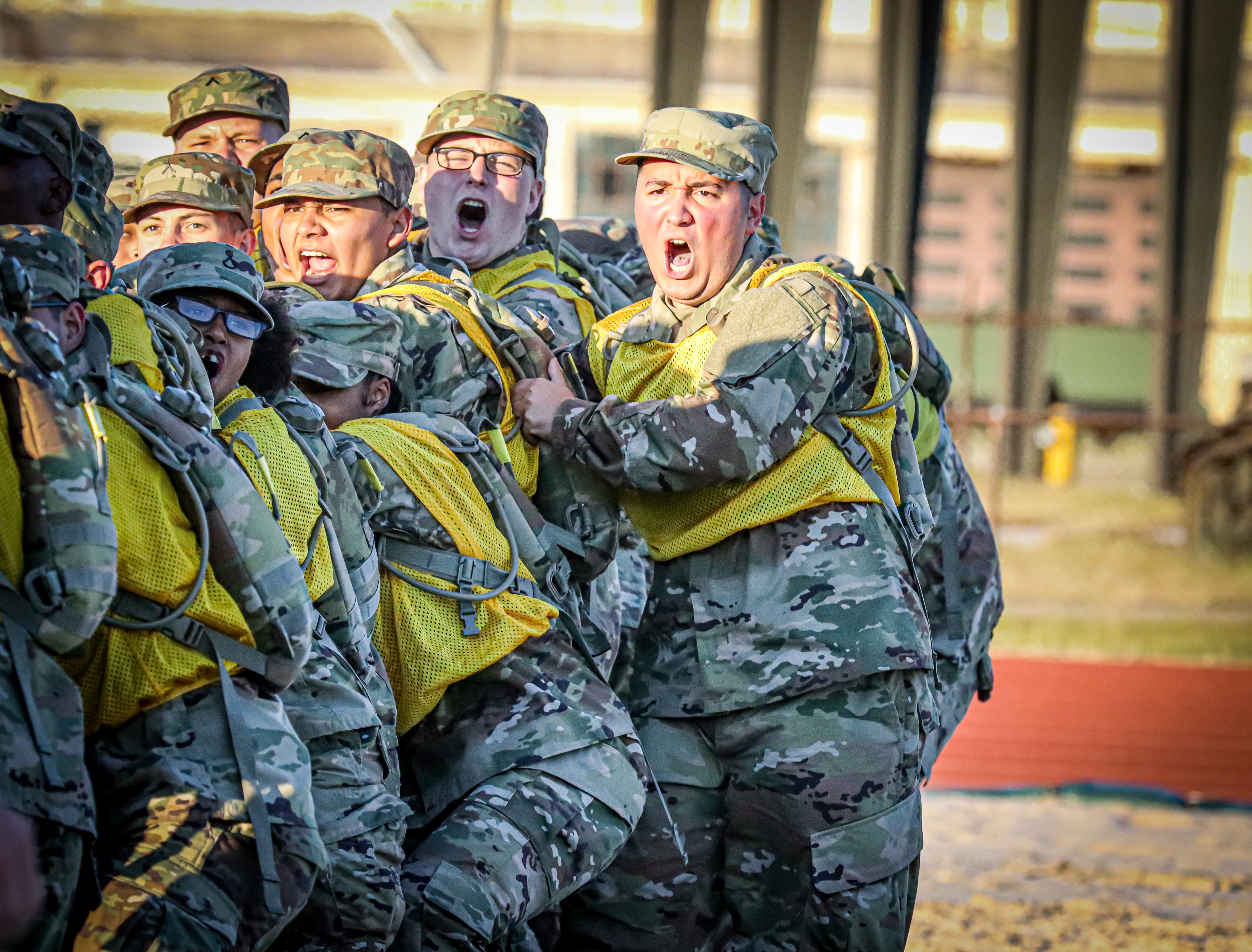

Brito pointed to recent changes in basic training, creating the “Forge 2.0″ that builds on individual soldier tasks and training by putting even the newest recruits in small unit leader positions.

The concept has been part of basic training since at least 2021. It was part of changes to training to encourage problem-solving among recruits and to add leadership opportunities at even the earliest points in a soldier’s training.

Army Times reported in 2020 about the end of “shark attacks” for infantry recruits. The practice, long standard in Army and Marine Corps training, involved drill sergeants rushing recruits and overloading them with stressful commands, yelling and chaos.

The goal, originating in the draft military, was to establish “psychological dominance” over trainees so they would submit to instruction and follow orders.

Instead, the Army instituted the “First 100 yards” for new infantry recruits, a nod to the common “Last 100 yards” of close-in combat that the services expect from their infantry.

Now, infantry recruits conduct the first 100 yards as a five-phase event, which was developed by senior non-commissioned officers at the Infantry School.

In its early development, Army Times reported that training required soldiers to:

• Memorize information about their unit histories and chains of command.

• Conduct a simplified resupply mission.

• Perform events from the Army Combat Fitness Test, including leg tucks, standing power throws and push-ups.

• Observe an infantry squad and weapons demonstration.

The template for decades, Brito said, has been a “round robin” style of training. That style has a soldier work through their individual tasks until they become experts. That’s not gone away, in fact, it’s crucial to the next step, which is solving problems as a team.

Brito said a current pilot program at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, called Forge 2.5, is expanding the chances for a new soldier to serve in a leadership role.

In one example, Brito told Army Times, a drill sergeant might take on the squad or platoon leader role in an event while a junior soldier serves as a team leader. Or the group may act as a simulated platoon for a particular training event and various recruits would serve in different leadership roles.

“So, let me fast forward and come out at 10 weeks great at my individual skill, but I also know the value of my battle buddy, my teammate, my squad,” Brito said.

That helps build team cohesion through peer leadership both in early exposure to Army culture and in warfighting proficiency, he said.

The two prongs fall within two of the acting Chief of Staff of the Army Gen. Randy George’s focus areas: warfighting and building cohesive teams.

Recruits now also hear more about Army history and culture through added lessons about the force.

“It’s going to make a difference in the troop that gets out of training and moves on to his or her respective (Advanced Individual Training),” Brito said.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.