Who owns the National Guard? It’s complicated.

A recent court ruling in Texas could complicate matters further. The stage is set for a fight over control of the Guard — and this time, the states have the upper hand.

For more than a century, the federal government’s authority over the National Guard has steadily increased, as has its usage overseas.

States, who once held near-total control over their militias, sacrificed autonomy on the altar of a federal financial firehose, which gave the Defense Department leverage to shape the Guard in the image of its full-time counterparts. In return, governors now have highly trained forces at their disposal for missions at home, and they’re using them more often than ever.

Both sides have benefitted from this deal since 1990, when the Supreme Court unanimously decided the last major legal battle in favor of the DoD.

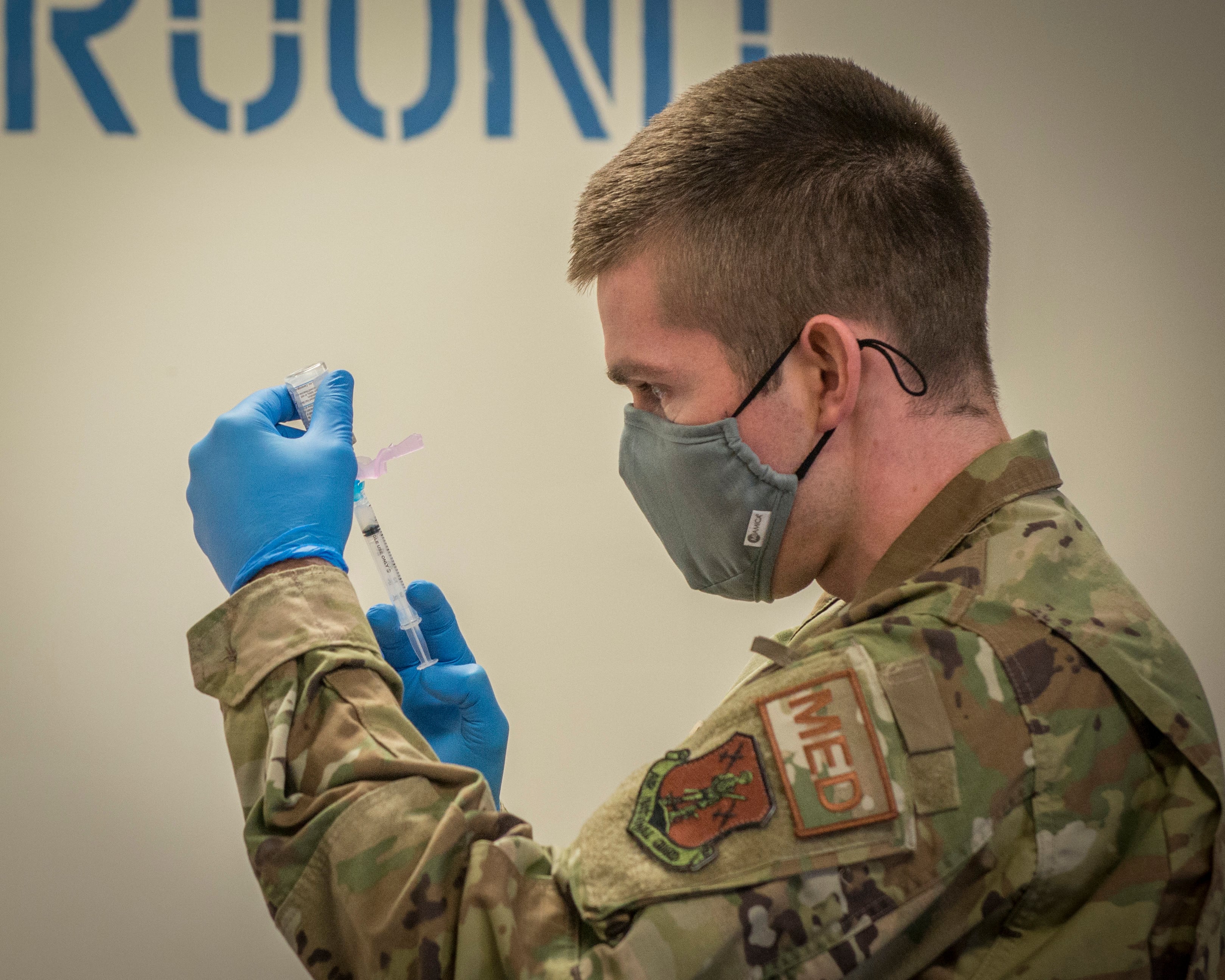

But the deal may soon be dead, experts say, after a recent court ruling in Texas Gov. Greg Abbott’s legal fight against the Pentagon’s COVID-19 vaccine mandate.

Army Times reviewed court documents, researched historical cases and spoke to legal scholars about the ruling, the ongoing legal battle, and its potential impact on the Guard.

“What the ruling essentially says is that state compliance with federal guidelines is completely voluntary,” said Jeff Jacobs, a retired Army Reserve two-star general, attorney and author of a 1994 book analyzing the Guard’s dual control structure. “And the only recourse the federal government has — because Texas did not dispute this — is to withdraw funding for [the state’s] National Guard.”

Jacobs warned this decision at its “logical conclusion” allows governors to block military personnel requirements, offering free rein to protect non-federalized Guard members from military punishments for everything from marijuana use to fitness tests. But even under the ruling, troops must meet all federal requirements to join.

“It gives the governor[s] a veto to play politics with every single thing that the Secretary of Defense or the Secretary of the Army or Air Force do,” the retired general warned.

Both the DoD and the National Guard Bureau declined to comment, citing ongoing litigation. In an emailed statement, Abbott spokesperson Andrew Mahaleris said the governor “appreciate[s] the Fifth Circuit’s adherence to the rule of law, and Texas will not stop fighting until the brave men and women of our military receive the full benefits they have more than earned.”

The Abbott administration, later joined by Alaska’s governor, asked a federal judge in Tyler, Texas, to block the DoD’s vaccine mandate in January 2022.

In court filings, the governors claimed that “only the state, through its governor, possesses legal authority to govern state National Guard personnel” when not mobilized under federal control, regardless of who is cutting the drill checks.

Responding to the governors, the federal government contended it has the authority to set readiness requirements and enforce them. They contended that in order to receive federal pay and federal benefits — even when in a state-controlled, federally-funded Title 32 status — members of the Guard needed to comply with federal readiness requirements.

After in-person arguments in June 2022, U.S. District Judge J. Campbell Barker denied the governors’ request for a preliminary injunction, a rare pre-trial declaration that would have blocked the vaccine mandate for Guardsmen nationwide.

The Abbott administration appealed the denial to the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, and the result could upend federal control of the Guard.

A shot over the bow

Within the context of the case, the court’s decision was minor, explained Jason Mazzone, a law professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign’s College of Law.

A panel of three appeals judges unanimously voted to vacate — or undo — Barker’s denial of the preliminary injunction. The lower district judge must reconsider the matter in the months ahead, and final resolution could be years away.

But when appeals courts vacate district court decisions, as the 5th Circuit did on June 12, they typically publish a legal opinion, a memorandum explaining their reasoning that provides legal guidance to lower courts about the issue. According to Mazzone and Jacobs, pre-trial opinions often foreshadow later decisions.

The June 12 opinion, written by U.S. Circuit Judge Andrew Oldham and signed onto in part by U.S. Circuit Judge Don Willett, left little to the imagination. Oldham, who was appointed by former President Donald Trump, ascended to the 5th Circuit on a 50-49 Senate vote in 2018. He spent the previous three years as an official lawyer for Abbott, culminating as his office’s general counsel.

The panel’s third member, U.S. Circuit Judge Carl Stewart, declined to join the opinion.

“The President of the United States asserts the power to punish members of the Texas National Guard who have not been called into national service,” Oldham said. “The Constitution and laws of the United States, however, deny him that power.”

The ruling overturned Barker’s analysis for the lower district court. Barker held that the federal government can withhold pay and punish members of the National Guard who refuse to comply with readiness requirements. That’s because Guard troops hold simultaneous and overlapping, but legally distinct, memberships in their state’s organized militia and the federal National Guard, Barker argued.

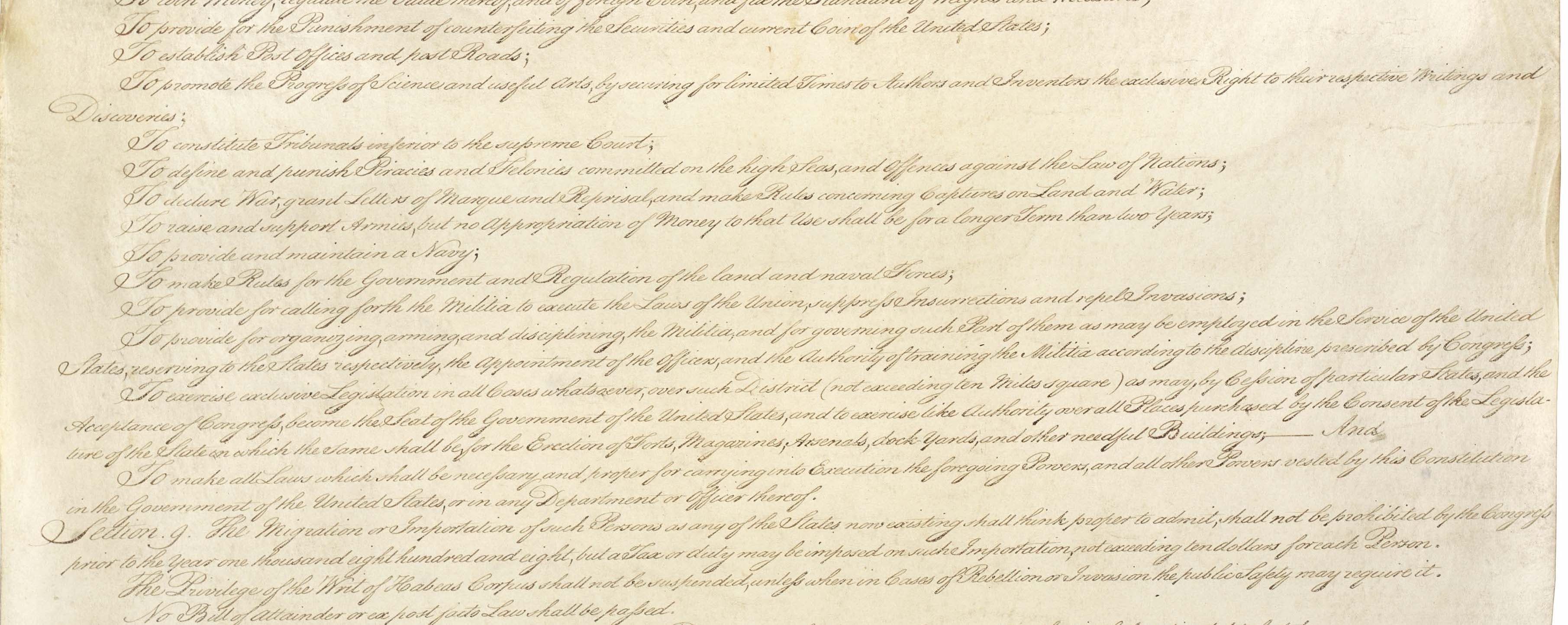

But Oldham disagreed. He analyzed the Constitution’s Militia Clauses, which were a 1780s power-sharing compromise between the federal government and the states. The states feared the potential tyranny of a federal government with a large standing Army, but the Federalists, who favored a strong central government, argued that Congress needed to defend the country.

Under that bargain, the state militia had state-appointed officers and remained under state control on a day-to-day basis, though the federal government set their training standards. The central government also gained absolute power over the militia and its members if and when it was ordered into federal service to repel invasions or suppress insurrections.

Oldham acknowledged that later laws established the National Guard as the organized state militias and increased the federal government’s oversight and funding. But the government’s proposed punishments for Guard members who refused the vaccine mandate — which Oldham said may still occur, citing Military Times’ reporting — “unlawfully usurp Governor Abbott’s exclusive constitutional authority to ‘govern’ the non-federalized Texas militia.” That includes administrative actions like withholding pay and discharging troops.

Jacobs, the retired Reserve general, said Oldham’s reasoning could allow governors to defy any federal requirement they don’t see fit to enforce on their state’s National Guard.

“Let’s say you can’t pass a [physical fitness] test,” Jacobs said. “What Judge Oldham is saying is, ‘Well, Department of Defense [and] Department of the Army, you have no authority to yank that soldier’s recognition...[and] discharge him from the Army National Guard.’”

The federal government can theoretically federalize an entire state’s Guard to undo a governor’s orders, as President Dwight Eisenhower did in 1957 when the governor of Arkansas had deployed his troops to block Black students from integrating a school. But mass call-ups require significant political will, and Oldham noted that Biden appears “unwilling or unable to do so” to enforce the vaccine mandate’s punishments.

Responding to the federal government’s argument that federal laws give it punishment options for non-federalized Guardsmen, Oldham implied such laws are unconstitutional. “Regardless of whether the Government’s reading of these statutes is correct, the Constitution forbids President Biden from bypassing the States, stepping into Governor Abbott’s shoes, and directly governing Texas’s non-federalized militiamen.”

RELATED

Beyond federalizing the troops, the federal government’s only other option is to take federal funding away from the entire state’s National Guard, Oldham declared. But that idea hasn’t received serious consideration since the 1980s, when governors tried to block overseas deployments.

Not your granddaddy’s Guard

How did Oldham reach a conclusion that could reignite old debates?

The judge is an adherent of originalism, a conservative legal philosophy that places great weight on the original meaning behind the Founding Fathers’ words.

Originalist arguments often use historical analysis to examine how the Framers debated and explained the Constitution’s ideas, an approach that contrasts with other philosophies that consider the Constitution a living document and rely more on how officials and the courts have interpreted it over time.

Originalism coalesced as a theory in the 1980s and gained influence thanks to groups like the Federalist Society, who partnered with conservative politicians to place originalism-minded lawyers into federal judgeships. Five of the Supreme Court’s nine current justices are current or former members of the Federalist Society.

Mazzone, whose Militia Clause research was cited heavily by Oldham, praised the judge’s “sophisticated” analysis.

“[His] use of historical sources was very good,” said Mazzone. “I think he got the story right about the militia…its role, and concerns about who’s going to control it.”

But both Mazzone and Jacobs, the retired Reserve general, questioned whether originalism is an appropriate framework for analyzing the modern National Guard. Today’s Guard, a much smaller all-volunteer force, is highly professionalized and depends on federal funds for organization, equipment, training, paychecks, facilities and more.

Jacobs argued that Oldham “ignores the major thrust” of the 1990 Supreme Court case, Perpich v. Department of Defense, which centered around Guard members’ voluntary enlistment in the federal National Guard. “That is decidedly not the construct that was in place in the 1790s,” he noted.

“I think it’s hard to equate the National Guard with the old militia,” agreed Mazzone. “It is a very different operation.”

The old state militias were mandatory for all adult male citizens, he explained, so giving the federal government “the ability to punish” non-federalized members could have allowed it to punish any male citizen at any time. Today’s National Guard, by contrast, is an all-volunteer force.

Mazzone also contrasted the old militia with the modern Guard’s federal organization, professionalism derived from federal training, and federal funding.

“It’s much closer to being part of the federal military rather than the traditional militia,” he said. Until the early 1900s, militia members didn’t even have standardized weapons.

But in the case Oldham reviewed, neither the government nor the governors argued that the Guard isn’t equivalent to the state militias of yore — and the Guard proudly celebrates its roots in the colonial militias of the 17th century.

“I think there’s a real question about that,” said Mazzone. He argued that the original militia “doesn’t quite have an analogy today, when the numbers are quite smaller.”

What’s next?

Even after Oldham’s ruling, the legal proceedings are far from resolved. The district court will soon resume considering the preliminary injunction in light of the opinion, but a trial could be months or years away, experts said.

“This could be a year or more before we get a final resolution in the case,” Mazzone noted. “If the Biden administration loses and decides to go to the U.S. Supreme court, that could prolong the case for a couple more years while the court decides whether or not to grant review of the case.”

The scholar added that the Supreme Court “almost always grants review in a case in which a lower court has invalidated something that the federal government has done on constitutional grounds.” The “wrinkle in this case” that could see it resolved on a technicality, he noted, would be if the Pentagon backs down on punishing Guardsmen who refused the vaccine.

Moreover, today’s Supreme Court — more originalist than ever before — could take a different view on control of the Guard than their predecessors did in 1990, the experts agreed.

It’s also not clear whether Oldham’s ruling would eventually require back pay or reinstatement for Guard members punished for vaccine refusal.

Meanwhile, the opinion sparked internal conversations among National Guard Bureau lawyers, who are watching the case closely, a source familiar with the discussions told Army Times. Bureau spokesperson Deidre Foster confirmed the conversations in an emailed statement, but downplayed them as routine.

Jacobs said the ruling, should its precedent expand, raises questions about the uneasy bargain that emerged when the active duty force ceded combat power to the Guard during late- and post-Cold War drawdowns.

“It’s not an efficient organizational structure for the national defense force of a superpower, exactly for the reasons that created this litigation,” he said.

The retired general, who once commanded Army Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations Command, said the government is likely to fight the case.

“I cannot fathom that DoD will just let this opinion stand,” Jacobs said. “It would throw things into chaos.”

Davis Winkie covers the Army for Military Times. He studied history at Vanderbilt and UNC-Chapel Hill, and served five years in the Army Guard. His investigations earned the Society of Professional Journalists' 2023 Sunshine Award and consecutive Military Reporters and Editors honors, among others. Davis was also a 2022 Livingston Awards finalist.