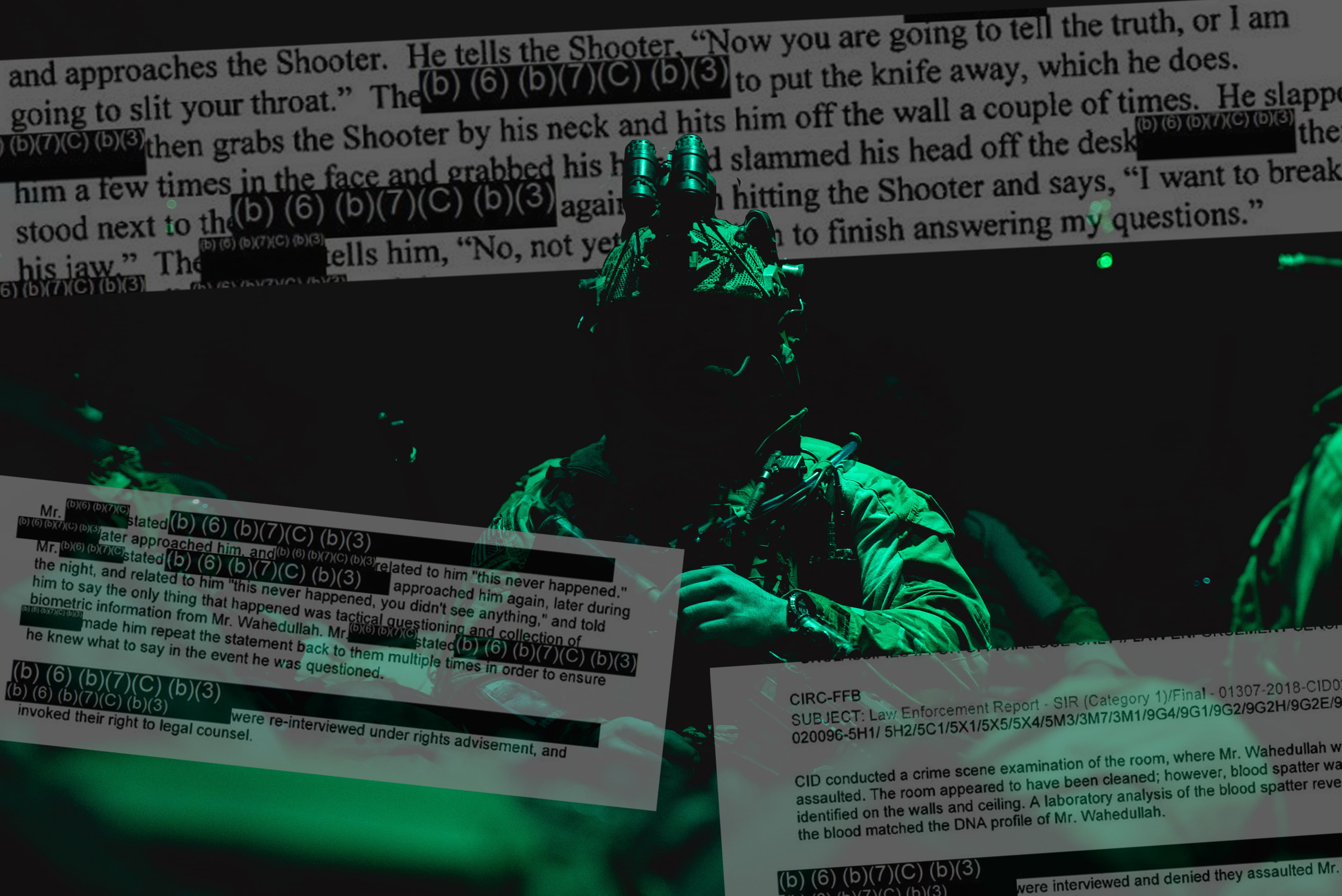

American Green Berets beat an Afghan commando, twisted his testicles and slammed him against a breaker box during an interrogation in western Afghanistan on Oct. 22, 2018, a civilian translator claimed as part of a criminal probe that only closed last year.

The commando, Wahedullah Khan, was detained after he opened fire on Czech special operators, killing one and injuring two others. Wahedullah was captured, handed over to NATO forces and interrogated in a cramped room on Shindand Air Base, according to the redacted case file obtained by Military Times through a Freedom of Information Act request and reported here for the first time.

“I want to break his jaw,” the translator recalled one U.S. soldier saying. “No, not yet,” another responded, according to the translator. “I need him to finish answering my questions.”

Hours later, Wahedullah was dead from blunt force trauma. The translator said Americans approached him that same night and told him to keep quiet about the incident.

“Forget that this happened,” the translator recalled several soldiers warning him. “You didn’t see anything.”

Soon, the Green Berets came under scrutiny from the Army’s Criminal Investigation Division for conspiracy, obstruction of justice, aggravated assault, voluntary manslaughter and murder. They denied harming Wahedullah and blamed the death on other Afghan commandos.

Blood found in the Green Berets’ interrogation room during a crime scene examination suggested another course of events.

“The room appeared to have been cleaned; however, blood spatter was identified on the walls and ceiling,” Army CID’s final report stated. “A laboratory analysis of the blood spatter revealed the blood matched the DNA profile of Mr. Wahedullah.”

The case closed in May 2021. All evidence was turned over to 1st Special Forces Command, where leadership decided against prosecution.

General officer memorandums of reprimand were instead issued to eight Green Berets from 7th Special Forces Group, including a captain, a chief warrant officer, a master sergeant, three sergeants first class and two staff sergeants. All names were redacted in the case file, but six letters were permanently filed, meaning they will follow those soldiers throughout their careers.

“In this case, the investigation’s results did not present sufficient evidence of misconduct beyond a reasonable doubt for any of the offenses, which is the standard required to obtain a conviction at court-martial,” Maj. Dan Lessard, spokesman for 1st Special Forces Command, said in a statement. “Furthermore, there was not probable cause to believe that the most serious alleged offenses, including murder, had occurred.”

Officials at 1st Special Forces Command declined to provide copies of the reprimands to Military Times.

Even with the translator’s testimony, CID did not determine in its final report who delivered Wahedullah’s death blow. Wahedullah was passed between troops from three different countries over 10 hours and his blood was found in a room where both Americans and Czechs took turns questioning him.

‘He just lost his mind’

Wahedullah attacked at about 2 p.m. earlier that day.

Czech special operators were escorting a civilian truck onto Shindand Air Base when their rear vehicle suddenly took gunfire from a nearby compound owned by Afghanistan’s 4th Special Operations Kandak, according to the case file.

After Wahedullah opened fire, the Czechs raced three casualties to a medical clinic on Camp Conde, which was part of Shindand.

Afghan commandos later called the U.S. base to say they had the shooter in custody. The Afghans arrived with Wahedullah at roughly 5 p.m. He was dressed in a track suit with sandals, according to an American who escorted the Afghans to two Green Beret intelligence sergeants waiting near the interrogation room.

The American who escorted the truck later told investigators the building was chosen because it was far away from the medical evacuation area and from unnecessary personnel watching everything unfold.

U.S. forces needed to know whether another attack was coming, according to the investigation. The base heightened its security posture following the shooting. And Jaguar 50, call sign for the Green Beret team’s JTAC, a close air support specialist, spotted an individual crawling towards the camp with a satchel when helicopters came for the Czech casualties.

The Americans watched the crawling man but didn’t shoot.

With the help of the translator, the Green Berets sifted through Wahedullah’s phone and other personal items for shreds of useful information. Meanwhile, the Czechs interrogated Wahedullah. The translator told investigators he heard screams coming from inside the room.

The Green Berets and the translator entered next. They wanted to know if “there were more people or threats waiting,” one Green Beret later told investigators.

The Green Berets denied harming Wahedullah during questioning. They said the turn-coat commando failed to answer most questions. Wahedullah told them he had been feeling ill and went “crazy” while on guard shift.

“He did not know the names of any of the soldiers he lived with, ate with, or prayed with because he was new to the unit and had only been there for five months,” one Green Beret stated. “Again we asked him who hired him to do this or why he did it and he insisted he just lost his mind. We could not get him to explain if it was in retaliation or if he had ever been in contact with the Taliban.”

Wahedullah at one point recalled Americans mortaring his village years ago, killing three women.

“He claimed that Americans make mistakes all the time when they kill innocent civilians and it was the same as his mistake,” another Green Beret stated. “When asked to further elaborate on that comment he just kept referring to that he went crazy.”

‘You never saw anything’

The Americans questioned Wahedullah for about 30 minutes before turning him back over to Czech special operators, according to the investigation. Wahedullah wasn’t harmed while in either group’s custody, the Americans said.

In a statement made days after the shooting while still on Camp Conde, the translator largely agreed with the Green Berets’ version of events. But on Nov. 7, 2018, now on Bagram Air Base and away from the remote camp, the translator provided a statement with a far different narrative.

During the interrogation, a zip-tied Wahedullah was repeatedly assaulted by multiple Americans from 7th Special Forces Group, the translator told investigators at Bagram.

The Americans choked Wahedullah, hit him in his crotch, slammed his head off objects and beat him, the translator alleged. One of the interrogators brandished a knife, the translator added.

“Now you are going to tell me the truth or I am going to slit your throat,” the U.S. soldier warned, according to the translator. But another man, who the translator referred to as “chief,” told him to put the knife away.

At one point, a Czech soldier entered the room.

“He had big eyes, and was bald, and started choking the shooter and spitting on him, grabbing his hair, he yelled at the shooter and pounded on the desk,” the translator stated.

Questions were asked during the interrogation. But Wahedullah had a “hard time talking” and “struggled to answer,” the translator said.

Eventually, the Americans decided they wouldn’t get any information and ended the interrogation. The translator claimed that the last time he saw Wahedullah outside the room, the man was bleeding from his nose and mouth, and his face was swollen around his eyes and forehead.

The translator said he was then approached by an American and told, “Listen, this never happened, you never saw anything, forget this.”

Later that night, more Americans knocked on his room door.

“They told me, if you are ever asked what happened to tell them we only asked a few tactical questions and collected biometric information and then left,” the translator stated. “They asked me to repeat it several times, which I did.”

Wahedullah was turned back over to his unit at roughly 7 p.m. Other Afghan commandos put him in the bed of their Ford Ranger truck. An Afghan commander ask why Wahedullah was in the back, according to the translator, who was present.

“He was bleeding so badly, we put him in the back instead of the back seat,” the other Afghan commandos answered.

‘They beat him’

Hours later, an individual from the U.S. Special Operations Task Force in Afghanistan called the operations center on Camp Conde to say they received reports that Wahedullah was about to die after he was abused by Czech forces. It wasn’t clear from the redacted investigation how the task force learned of the situation.

Regardless, Wahedullah was once again brought back to the Americans, this time in an attempt to save his life. He arrived on a stretcher. A dressing was over his head, an IV was in his arm and a plastic tube was inserted into his nasal airway to help him breathe, according to an American doctor who saw Wahedullah at Camp Conde’s clinic.

Wahedullah had no pulse when he arrived. A surgical team tried to resuscitate him, but to no avail. After he was pronounced dead, one doctor turned to the Afghan sergeant major who brought the beaten body and asked questions.

“l asked what happened and [the sergeant major] answered me, ‘They beat him.’ I asked when and he repeated it,” the surgeon said in his witness statement.

While in the clinic, the Afghan sergeant major said openly that every commando at the 4th Special Operations Kandak “had a go” at Wahedullah, implying they were the ones who beat him, several Green Berets stated.

When investigators questioned one of the Green Berets further about this exchange, and who heard it, the soldier explained that the surgical team was too far away and distracted to listen in.

The translator, who was also in the clinic, disputed that the Afghan sergeant major made those comments. “No, l never heard that,” the translator stated, adding that those individuals never spoke in the clinic.

Czech officials conducted their own investigation into Wahedullah’s death, according to the case file, but those details were withheld in the copy provided to Military Times because it was considered third-party information.

Czech Ministry of Defense spokesman Jakub Fajnor told Military Times that their investigation remains open, but declined to comment further.

“The Ministry of Defense of the Czech Republic is not allowed to comment on an ongoing investigation,” Fajnor said in an email. “The supervising public prosecutor’s office in Brno has reserved the right to provide information about the case. According to our sources, the public prosecutor’s office is planning to contact the American authorities with a cooperation request.”

The Czech prosecutor’s office in Brno did not return a request for further information.

‘I know I can’t do that’

The case file indicates that Czech special operators were highly regarded by Americans. One Green Beret, who the redacted investigation suggests was in a leadership position, said in his statement that Czech troops took great pride in being one of the few allied forces to conduct missions outside the wire.

The Czechs wouldn’t have done anything to jeopardize that, according to the Green Beret leader, who was interviewed as part of the investigation but who was not present during the interrogation or Wahedullah’s handoff.

He also told investigators about an encounter he had hours after the attack. An individual, who contextual clues in the case file suggest was a Czech commander, walked into the American’s office and shut the door.

“He was visibly upset [over Wahedullah’s attack] and frustrated yet composed,” the Green Beret leader said. “He had tears welling up as he told me, ‘I want to kill him, that shooter needs to be dead, but I know I can’t do that.’ It seemed he needed to vent in private where his guys couldn’t see.”

The translator’s second statement, which implicated both Green Berets and Czech troops, was made two weeks after the incident.

Some disturbing accusations remained the same in both statements, including that the translator heard screaming while Czech troops were questioning Wahedullah without Americans and that Wahedullah was bleeding badly when turned over to the other Afghan commandos. But the translator’s detailed account of Green Berets beating Wahedullah was new.

Defense lawyers could’ve pounced on that change, said retired Army Lt. Col. Franklin Rosenblatt, who served as the lead military defense counsel for Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl, an American held captive by the Taliban for five years after deserting his post.

However, the translator could’ve also explained in court why he initially withheld details.

“There could be reasons why [the translator] did this. If he was under some sort of coercion or threat or intimidation before and once he was free of those things, he was liberated to speak and said what he had to say,” Rosenblatt explained.

When Wahedullah’s death first became public, it was reported that the Green Beret team had been withdrawn early from Afghanistan.

Taking troops out of a war zone where alleged crimes occurred can make cases more difficult to prosecute because of difficulties obtaining the necessary evidence and witnesses, according to Rosenblatt, who has argued that the court-martial system should be able to follow U.S. forces on deployment.

“These are crucial Afghan witnesses,” Rosenblatt said. “Good luck being able to identify them and work out the visa issues to get them here. The Czech soldiers, they’re also essential witnesses for this. The prospects for prosecution, even if the prosecution did have merit, really changed once everyone flew back to the States.”

The general officer memorandums of reprimand, or GOMORs, may have been the most aggressive action available given the problems with investigating this crime. When permanently filed, as they were for six of the Green Berets, GOMORs can end a soldiers’ career.

“Credit goes to [1st Special Forces Command] for seemingly doing all that could be done in this situation,” Rosenblatt added. “The result of permanently filed GOMORs is significant and will likely have career consequences for each of those implicated.”

Kyle Rempfer was an editor and reporter who has covered combat operations, criminal cases, foreign military assistance and training accidents. Before entering journalism, Kyle served in U.S. Air Force Special Tactics and deployed in 2014 to Paktika Province, Afghanistan, and Baghdad, Iraq.