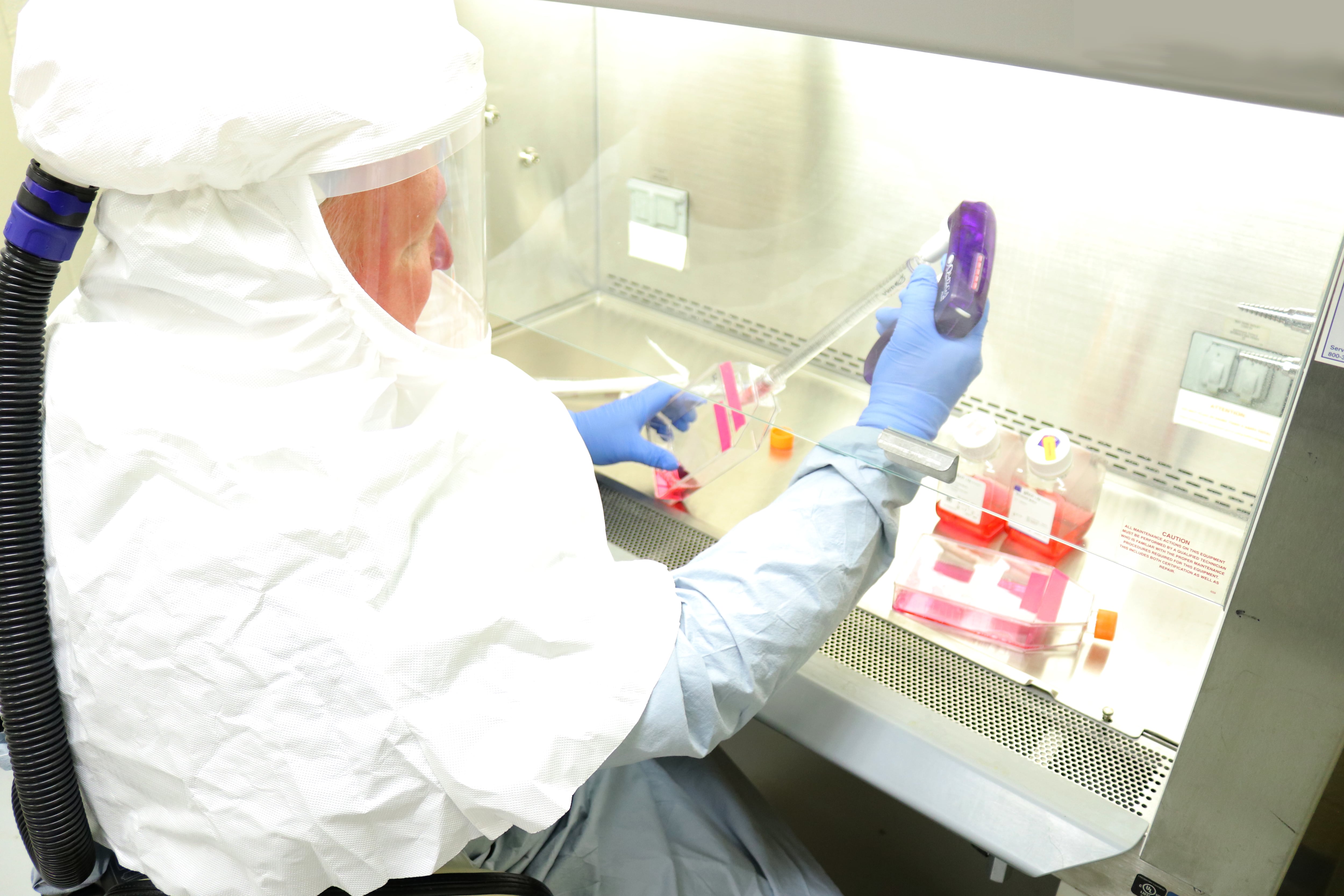

A kind of catch-all vaccine that could protect against current and future strains of the coronavirus that sparked the COVID-19 global pandemic has already been tested by Army scientists on mice, monkeys, horses, hamsters and even sharks.

Early human testing has begun and researchers expect the first data sets on immunity in the coming weeks. This effort is a new approach to handling viruses, finding ways to defeat families of viruses rather than a specific strain.

And that’s important because medical experts worry that the next pandemic-triggering virus could be more contagious than COVID-19 and far deadlier.

“We know it’s safe and tolerable but we don’t know yet the immunity it confers,” said Dr. Kayvon Modjarrad, director of the emerging infectious diseases branch at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. He spoke during the Defense One 2021 Tech Summit on Monday.

RELATED

Modjarrad said that the results so far in animal studies have shown high immunity. If even a fraction of that is present in humans, their current vaccine would be a good option for a next-generation vaccine to combat coronavirus, regardless of the strain.

Their broad-spectrum coronavirus vaccine could also serve as a “booster” shot for soldiers that would offer longer and more durable protection against future variants, Modjarrad said.

The push is an effort to produce robust vaccines that target a family of viruses, rather than past efforts which pursued specific immunization against certain strains. That method is too slow to meet the types and volume of viruses that humanity may face in the coming years.

“We’re chasing the wrong curve of the virus after it emerges,” Modjarrad said.

The goal is to have a vaccinated population before a virus can make an impact.

“We’ll get to the point where we can stop the virus in its tracks before a pandemic,” he said.

There have been at least six “notable variants” of the coronavirus detected so far in the United States since the pandemic first arrived in early 2020, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Modjarrad spoke along with Dr. Dimitra Stratis-Cullum, program manager for transformational synthetic-biology for military environments with the Army’s Combat Capabilities Development Command.

Stratis-Cullum’s work focuses on making synthetic materials that can be used for a host of applications.

Her work over the past year has focused on making medical diagnostic items, but also jumped very early into building methods for testing plasma of convalescent COVID-19 patients that could be used to help others recover.

Through CCDC and ARL, her team continues to build an “immunity library” so that first responders can quickly screen any type of disease they encounter and be prepared with the right kind of tools and approaches when they arrive at a location.

Stratis-Cullum’s group is partnered with Modjarrad’s team in finding where and how the coronavirus “binds” to a receptor in the body. By developing synthetic methods to prevent the binding in the first place, they hope to keep the virus at bay even if it enters the body.

One of the ways in which Modjarrad’s group has approached the problem is to use a nanoparticle vaccine that uses ferritin, which has been effective against the current COVID-19 virus and another coronavirus from 2003, the SARS-CoV-1.

The ferratin iron-carrying protein somewhat resembles a sphere like a soccer ball, Modjarrad said. The structure has 24 faces on its exterior.

Scientists can place any type of virus particle they want the human body to recognize on those faces. Then the immune system reacts to it because it resembles the actual virus that the system will face if exposed.

And, by having so many options, researchers can target specific structures in the virus they’re studying to be carried by the nanoparticle to the body.

They can mix and match parts that are core to the coronavirus and will be part of any strain that could emerge, he said. The body then has had a chance to identify from the vaccine what it needs to defeat any future virus it might encounter.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.