Michaela Maloney was walking a local beach near her home in Kodiak, Alaska this past November, looking mostly for beach glass, made smooth by years of waves and sand.

Maloney makes art with some of the pieces she finds and sometimes sells old glass bottles or other items she finds as part of her small, local business.

But on this particular day, she spotted something shiny as the tide had receded and bent down to pick it up, rubbing it between her fingers. The small metal disk had writing on it but didn’t look quite like anything she’d seen before. Mostly the metal that washes up is old kitchen utensils.

Shew knew that this beach, known by locals as “Junk Beach,” was near the site that military units dumped a lot of gear in the ocean during World War II and for years afterward. She thought that this must be an old-school dog tag from one of the troops stationed here or passing through a half-century or more ago.

“There’s a lot of people who find a lot of interesting stuff here,” Maloney told Army Times.

Maloney had heard stories of people finding old metal buttons, bullets and even dog tags. But often the scrap was molded together in big heaps, hardly identifiable.

Nearly two hours of scrubbing later revealed a name, Melvin R. Herrod and a number, 0546292.

She called her father, William Maloney, who was an Army veteran. He said it was definitely an older-styled dog tag used at that time, circular rather than the more oblong shape used today.

“I just kind of felt like it wasn’t mine to keep,” she said. “It’d be pretty cool to find the family it belongs to.”

Within a few quick searches and verifying some information through the National Archives website, she’d found a man named Melvin Herrod on Facebook. She sent him a photo of the dog tag and asked if this might have been his or anyone related to him.

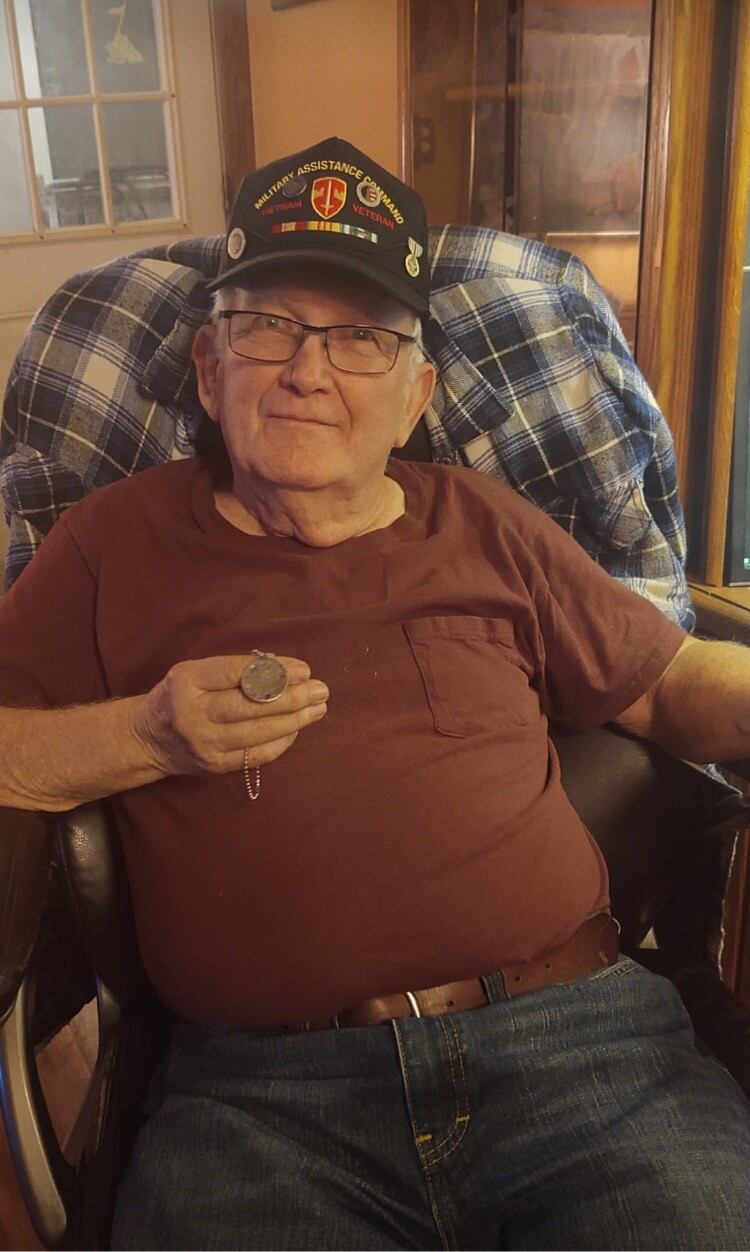

Melvin “Shorty” Herrod told Army Times in a phone interview that he was shocked to see this relic of his father’s service wash up on an Alaskan shore.

His father had died in 1971 in his mid-50s. Shorty Herrod’s parents had divorced when he was young and he was raised mostly by his grandparents. He didn’t know a lot about his dad other than he’d served in World War II. The pair reconnected before his father’s death but didn’t talk much about his military service.

The junior Herrod had also joined the Army in 1964 and served until he retired in 1990 having worked a range of jobs from telephone operator to missile crewman, security, equipment repair and military police.

Though he was born in Kodiak, Alaska, the 75-year-old had only ever visited the location once since he left as a child, and that was on a short refueling stop during a military flight.

“I don’t have anything of his from the past and then I get that,” Herrod said. “I’m going to try and get his discharge papers.”

The find has sparked a renewed interest in Herrod to learn what his father did during World War II.

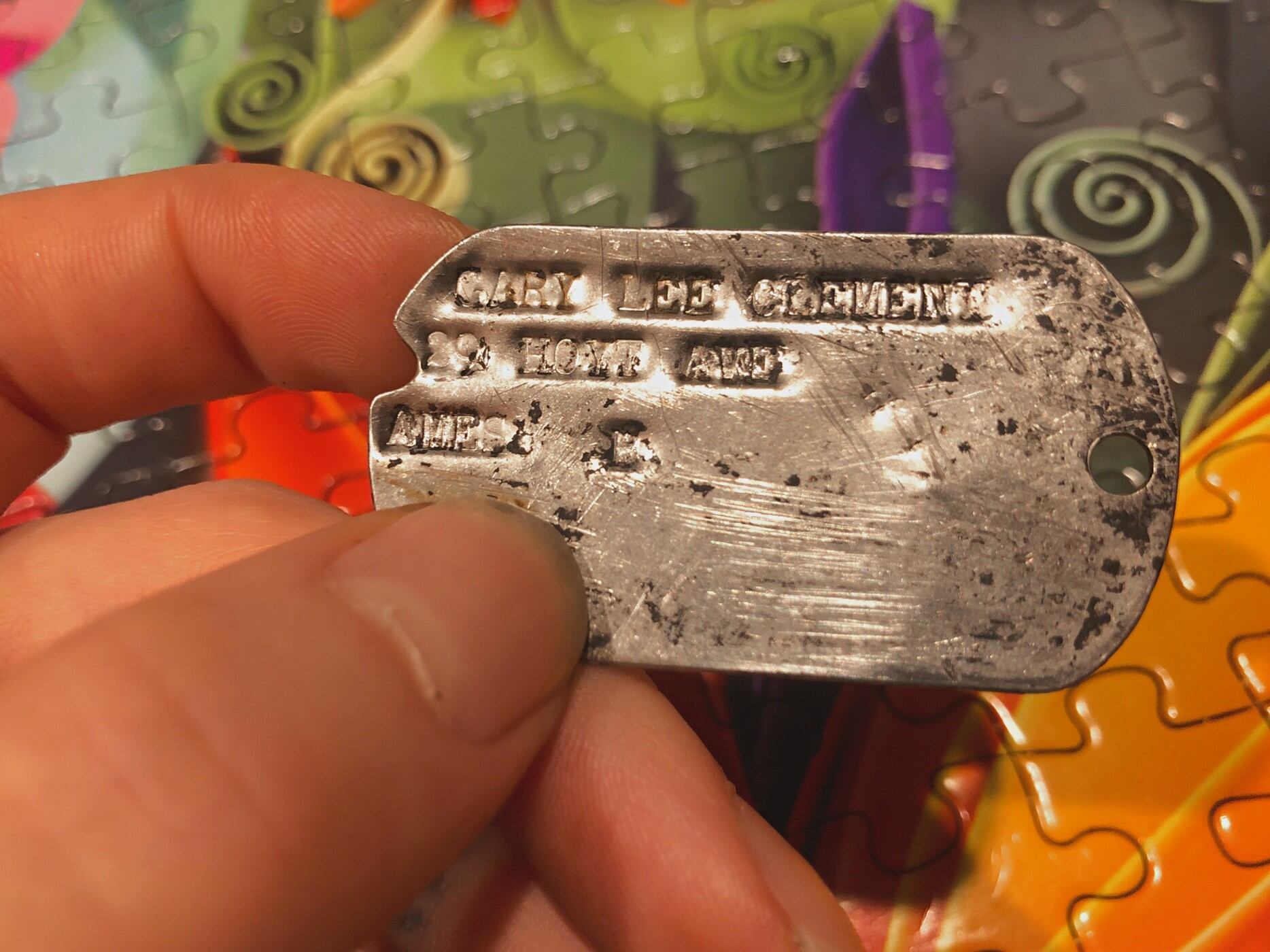

A few weeks after finding the Herrod dog tag, Maloney found a second dog tag in early December. This one looked more like the dog tags worn these days. She ran through the same research channels and was able to find data on Gary Lee Clement, a Utah man who’d served in the Army.

Sadly, one of the first references she discovered was his obituary. Clement had died in March 2020 at age 66.

But she was able to track down one of Clement’s brothers, who verified his brother’s service. And she mailed the dog tag.

While luck struck twice for Maloney’s key eye, she’s not alone in finding these pieces of personal military history.

Navy Times reported the story in May 2020 of Kristin Brown, who, in late 2019 was combing a site known as “Jewel Beach” near Kodiak, also looking for beach glass.

And that’s where she found a dog tag that had belonged to Willard Leslie Richerson, who she later learned served aboard a Navy patrol boat during World War II.

Richerson had died in 1999 at age 77. But Brown also tracked down Richerson’s family members through online obituaries and gravesite databases.

A granddaughter of Richerson’s responded and verified the information with her dad, Richerson’s son, also a veteran. Brown mailed the dog tag with a short note.

“When they received the dog tag they sent me an email with pictures,” Brown said. “It made my heart very happy knowing I was able to give them that piece of family history.”

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.