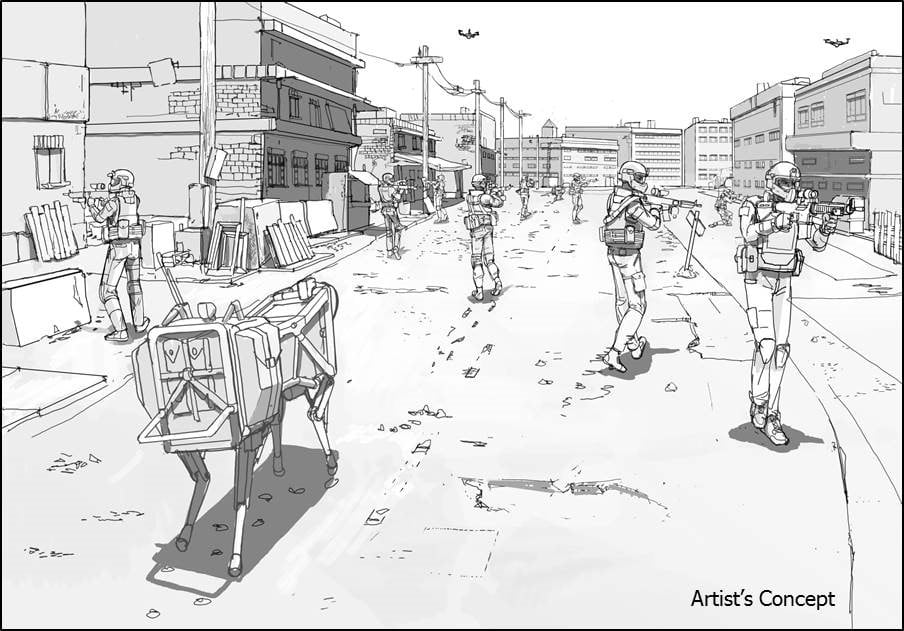

The Army’s plans for robotic wingmen in vehicle formations, a drone on every soldier and robotic mules carrying gear all aim to take the load off the fighter. But how will the two communicate, robot and human?

Voice commands like automated assistants on smartphones are great, but not when the threat of incoming fire means the robot battle buddy needs to decipher a range of priorities that humans might take for granted.

RELATED

Think more C3PO or R2D2 in the “Star Wars” movies than Hal in “2001: A Space Odyssey” —or better yet, a friendly cyborg from “Terminator” might be the best way to see your robot combatant squad mate of the distant future.

Enter research at the Army Combat Capabilities Development Command’s Army Research Laboratory.

A recent paper published by ARL’s Celso de Melo, a computer scientist, and Kazunori Terada at Gifu University in Japan, showed that emotional cues such as facial expressions and body language can be key factors in how machines and humans team-up. Those emotional expressions shape cooperation.

“People learn to trust and cooperate with autonomous machines,” de Melo told Army Times.

The computer scientists have spent a career working on how artificial intelligence perceives the surrounding environment, known as “computer vision.” He’s also done research into socially intelligent machines.

“I’ve always believed that we cannot get AI to be successful, we won’t have [full adoption] of AI in all of these aspects of life, unless we see the social skills we see in humans,” de Melo said.

For example, if a human member of the soldier-robot team is feeling particularly stressed, and the AI in the system can better read that stress and its effects, it can modify its communication to respond to the teammate.

“Human cooperation is paradoxical,” de Melo said in an Army release. “An individual is better off being a free rider, while everyone else cooperates; however, if everyone thought like that, cooperation would never happen. Yet, humans often cooperate. This research aims to understand the mechanisms that promote cooperation, with a particular focus on the influence of strategy and signaling.”

Whether we humans realize it or not, there’s a constant back and forth going on, verbally and nonverbally, when we communicate. That’s especially true when we are working in a team, toward a goal.

Something as simple as the timing of a smile can change a lot about how people perceive they’re being treated in a team.

“We show that emotion expressions can shape cooperation,” de Melo said. “For instance, smiling after mutual cooperation encourages more cooperation; however, smiling after exploiting others — which is the most profitable outcome for the self — hinders cooperation.”

While much of the general research about human-machine cooperation and communication is applicable to people in all situations, there are differences in military scenarios as compared with civilian settings.

This paper and research along these lines is still in very early development phases, de Melo said. Even within the AI research community, scientists like him and his collaborator, Terada, still work to convince their colleagues that this is fundamental to the future of robot-human teaming.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.