WOODRIDGE, Ill. — Leaders of a U.S. Army Reserve unit that controls thousands of soldiers across the western United States have mishandled at least two sexual assault complaints by not referring them for outside investigation, according to victims, their advocate and documents obtained by The Associated Press.

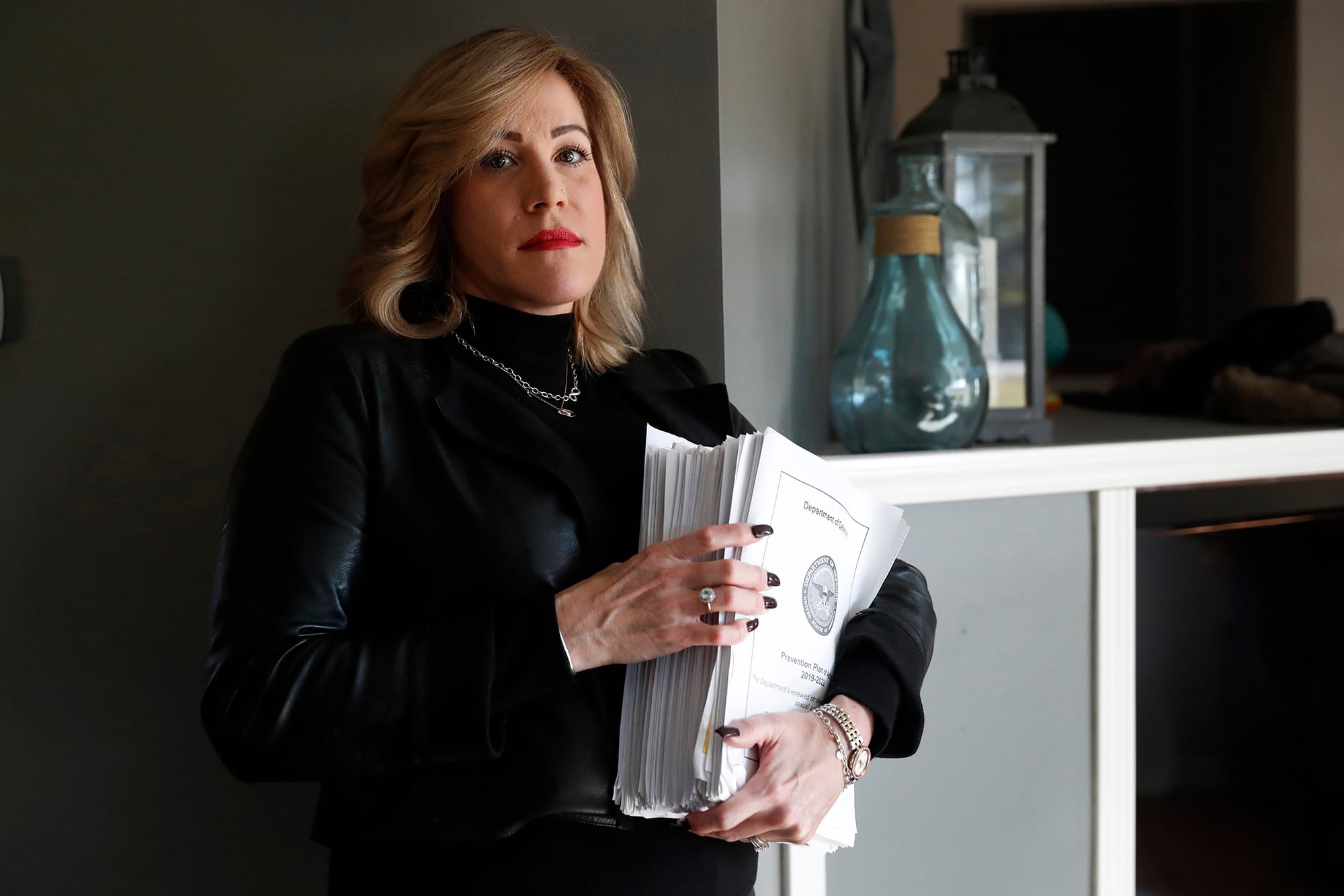

Amy Braley Franck, a civilian victim advocate with the 416th Theater Engineer Command, provided the AP with documents that show the command launched internal investigations into at least two complaints rather than refer them to the Army’s criminal investigation division as required by military policy and federal law. In a third case, they placed an alleged victim on a firing range with someone she had accused of sexual harassment, causing her to fear for her safety.

Commanders also have failed to hold monthly sexual assault management meetings, as required by DOD policy since 2006. And they ran the company without a sexual assault response coordinator for nearly a year and suspended Braley Franck after she alerted the Army to the internal investigations, she said.

“I can’t with a clear conscience say, 'Oh, yeah, report your sexual assault. We’ll take care of you,” Braley Franck said.

The 416th’s spokesman, Jason Proseus, said Army Reserve leaders take sexual misconduct seriously. He declined further comment, saying “the matter” was under investigation. He didn’t explain what matter was under investigation or by whom. The Army Reserve Strategic Communications’ chief spokesman, Lt. Col. Simon Flake, said the reserve doesn’t want to compromise the investigation or influence the outcome by commenting further.

The Illinois-based 416th Theater Engineer Command provides technical and engineering support for U.S. military forces. It serves as headquarters for nearly 11,000 soldiers in 26 states west of the Mississippi River.

Braley Franck said she has discovered multiple sexual assault administrative shortcomings and policy violations since she joined the 416th in February 2019 as a victim advocate. Her duties include supporting victims and connecting them with services .

She said the division went 10 months without a sexual assault response coordinator. Such coordinators ensure victims receive services such as medical care and counseling, help victims navigate the military criminal justice system and oversee victim advocates.

No one held a sexual assault management meeting during her tenure until this month, even though the DOD has required such meetings to be held monthly since 2006 to ensure a coordinated response and that victims are protected and can access services.

She said she has learned of at least two instances in which 416th commanders improperly initiated internal sexual assault investigations.

Federal law and Department of Defense policy require that commanders refer sexual assault complaints to criminal investigators in their respective branches. That’s intended to prevent commanders from brushing aside allegations involving their own people and to ensure that experienced investigators handle cases, said Rachel VanLandingham, a retired U.S. Air Force lieutenant colonel who teaches national security law at Southwestern Law School in Los Angeles.

Commanders who don’t follow proper channels can face reprimand, removal from command or a court-martial, VanLandingham said.

Internal sexual assault investigations cost the Wisconsin National Guard’s top commander his job in December. Gov. Tony Evers demanded Adj. Gen. Donald Dunbar resign after a federal investigation determined he had been launching internal probes rather than forwarding complaints to the National Guard Bureau.

In the first 416th case, Capt. Joseph Runhke of the 739th Engineer Company within the 416th investigated allegations from two soldiers that a male specialist had sexually assaulted a female private during a lunch break at the company’s base in Granite City, Illinois, in September 2017 and again outside the woman’s workplace in Springfield, Illinois, the following April.

In a memo Braley Franck provided to the AP, Runhke wrote that the woman told him both encounters were consensual, adding that the specialist’s tenure was almost up and trust would improve once he was gone. Under DoD policy and federal law, Army criminal investigators should have conducted the investigation.

The second case involves Spc. Sara Joachimstaler. The AP usually doesn’t identify sexual assault victims, but Joachimstaler gave permission to use her name.

She told her commanders that a sergeant repeatedly touched her leg during a car ride in March 2019 and groped her a month later while using her to demonstrate how to tie a rope around someone. She said her commanders did nothing.

Lt. Anthony Perkins, her unit’s executive officer, wrote in a memo that he notified his commander in April about Joachimstaler’s allegations and was told the commander would take care of it. In the memo, which Joachimstaler shared with AP, Perkins wrote that he reminded his commander that he had to report such complaints, but the commander refused to do anything and warned Perkins to back him up or he would be removed.

Joachimstaler took her complaints to the 416th’s inspector general but said she felt that office’s investigator, Maj. John Hill, tried to minimize her allegations. She told him in June that she wanted to take her complaints elsewhere. Hill sent Braley Franck a memo later that month asking her to initiate an investigation, a violation of the DOD’s ban on internal investigations.

Braley Franck referred both the third-party and Joachimstaler cases to the Army’s Criminal Investigations Division in June.

A judge advocate ultimately concluded there was no probable cause to believe the alleged perpetrator committed an offense in the third-party case. Braley Franck said Joachimstaler’s case is still under CID investigation.

Christopher Grey, a spokesman for the Army’s Criminal Investigation Command, said in a statement that he couldn’t comment due to “an ongoing investigation.” He didn’t elaborate.

Braley Franck was suspended on Nov. 20. Col. Gregory Toth wrote in a memorandum that she may have violated the code of ethics for victim advocates. He didn’t say how. Braley Franck maintains command’s leaders are retaliating against her for referring the cases to CID.

Human resource records show that Braley Franck was confronted in May 2019 about various alleged infractions, including improperly contacting the 416th’s commanding general, Miyako Schanley, directly to obtain an office; taking on coordinator duties and wearing skirts that were too short.

Braley Franck said she was trying to obtain an office where she could lock up victim files and that she wasn’t acting as a coordinator, but was providing advocacy because she was the only one who could since the 416th had no coordinator when she arrived. She also denied that she wore skirts that were too short.

Other documents show that Braley Franck took a call days before her suspension from a private concerned that she was being sent to the range for a live-fire exercise alongside the subject of her sexual harassment complaint and she feared for her safety.

According to a memorandum from another victim advocate who listened in on the call, Braley Franck called the new sexual assault coordinator, Regina Taylor, about the situation. Taylor responded “Hmm hmm, well, I guess we will just wait and see and hope for the best” and hung up.

Federal law and DOD regulations say supervisors in a victim’s chain of command are required to protect the victim from retaliation and maltreatment.

Proseus, the 416th’s spokesman, didn’t respond to an email seeking comment from Taylor.