In recent years, soldiers have seen a flurry of upgrades and new weapons, ammunition and optics added to their arsenal at a rate that outpaces previous decades of development in these areas.

Soldiers into their second enlistment today have a distinctly different weapons draw than they or their leaders did just a few years ago.

Those changes cover the full spectrum of small arms, both individual and crew-served weapons, mostly making existing systems lighter and more functional and adding new punch to the firepower of infantry squads, platoons and companies.

Some changes are not as easy to recognize, such as improved barrels, ambidextrous fire selectors and better bullets. Other shifts have added new systems or hold the promise of transforming small arms that are carried into combat.

RELATED

Those include a new pistol, improved carbine, better marksman and sniper rifles, advances in shoulder-fired rockets, better and lighter machine guns, submachine guns and even shotguns to blast drones out of the sky.

But even as the Army puts better optics, ammo and weapons into the hands of soldiers, it’s also looking for a way to move ahead of those systems being fielded. There are efforts to place a renewed focus on the individual soldier and squad, seeing even the smallest unit of firepower as worthy of investment in training, employment and hardware.

Next Generation Squad Weapon

The main weapon pulling in a host of Army resources is the Next Generation Squad Weapon program that’s developing both rifle and automatic rifle variants to replace the existing service rifle and squad automatic weapon.

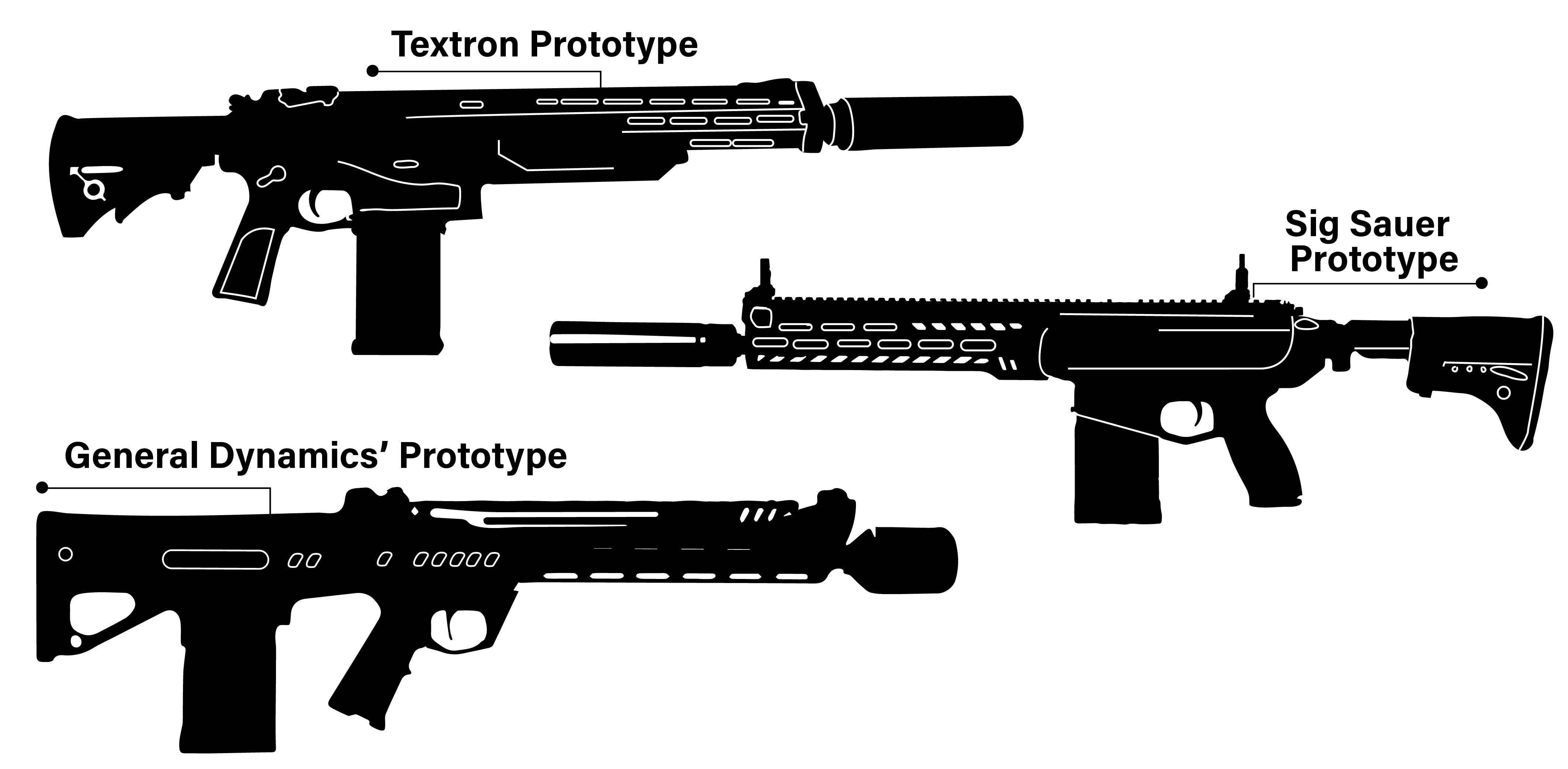

Three companies — General Dynamics, Sig Sauer and Textron Systems — are competing to build the weapon, which will be chambered in a 6.8mm round.

Textron has built the weapon around the new round in a “cased telescope” ammunition that uses a polymer casing and gives designers ways to put different types of round size, weight and propellant inside the package.

Sig Sauer is working with a more familiar rifle design, similar to its version of the current AR-type platform.

General Dynamics has offered a bullpup design, which has the magazine behind the trigger to maintain barrel length without lengthening the weapon. In the next two years the Army will determine which is likely to become its future rifle for infantry, combat engineers and scouts.

The 6.8mm intermediate caliber round was selected to increase lethality, accuracy and velocity. The aim is to design a weapon that is light enough to carry on long missions but accurate at farther ranges with the power to defeat tougher targets, including body armor.

But a piece of the NGSW that will provide future methods for improving marksmanship and lethal firepower at the individual soldier level will come from its fire control system.

That fire control is being developed separately and in parallel with the weapon itself for the first year and will merge with the weapon as it moves toward planned production in fiscal year 2022, according to a June 2019 presentation by Doug Cohen and Paul Koerner with the NGSW program at the National Defense Industrial Association’s annual armaments systems symposium.

But future prototyping includes plans for hi-tech advancements, such as automatic target recognition, target tracking, facial recognition, optical and aim augmentation, wind sensing, night sensing and ballistics computer.

Optics

This past year, some soldiers started receiving the most advanced night vision goggles the service has ever fielded, the Enhanced Night Vision Goggle-Binocular.

The new device gives soldiers a white phosphorous view rather than the traditional green tint, improving clarity. The binocular nature of the goggles allows for better depth perception, which improves target acquisition. The enhanced vision also lets users see through dust and smoke.

Army officials saw improved night shooting with the new goggle. And thermal capability gives the user even better ways to acquire targets not readily available in legacy night vision — all improving target engagement.

Along with better night vision, the rapid target acquisition, or RTA, capability allows for shooters to switch views from weapon to goggle or even add a “picture-in-picture” version so that they can shoot around corners or over barriers without exposing themselves.

RELATED

It works through a weapon-mounted camera that communicates wirelessly through the goggle.

The ENVG-B is only a small step toward a more ambitious project — Integrated Visual Augmentation System, or IVAS.

As the small arms themselves improve, shooting itself has the capacity to change through a marriage of high-tech hardware and ever-evolving software.

Early IVAS prototypes shown to Army Times at Fort Pickett, Virginia, this year use the Microsoft HoloLens device, a virtual reality goggle. The device has navigation features for wayfinding, can display the location of enemy and friendly troops and give map overlays to track in a heads-up display.

The core of what’s happening with the device relies on augmented reality — essentially software providing visual symbols in the user’s field of view. The user still sees the real world but can add and enhance what they see in their view.

While that might mean cool graphics and 360-degree experiences for video gamers, educational programmers and researchers, it can mean life or death for soldiers or Marines.

“No other piece of equipment has had this kind of impact since the introduction of night vision,” said Secretary of the Army Ryan McCarthy, a former Ranger, told Army Times. “This takes night vision to the PhD level.”

Ammunition

Better optics help soldiers find and target their enemies. Better firearms let them engage that target faster. But as retired Command Sgt. Maj. Matt Walker said at the June NDIA symposium, “ammunition is the ‘business end’ of what we do for a living.”

Changes in ammunition cover the shift to the 6.8mm round for the close combat formation’s next rifle and automatic rifle in the NGSW program. But researchers with small caliber ammunition are developing lighter ammunition, including polymer options over brass casings as well as new versions of the 7.62mm round used in the M240B and M240L machine guns.

And a long-awaited one-way tracer round is in development with initial production expected by early 2022, Lt. Col. Drew Lunoff, then-product director for small caliber ammunition at PEO Ammo, said at the June NDIA event.

But ammunition advances are not confined to small calibers. Lt. Col. Andre Johnson, product director for medium caliber ammunition briefed at the same event timelines for the 40mm portfolio. That may include day and nighttime impact rounds, low velocity rounds for training and high explosive airburst rounds for drone threats, all expected for production beginning in fiscal year 2023.

Though no timelines were shared, Johnson also said that funding had been restored for a door-breaching round in their portfolio.

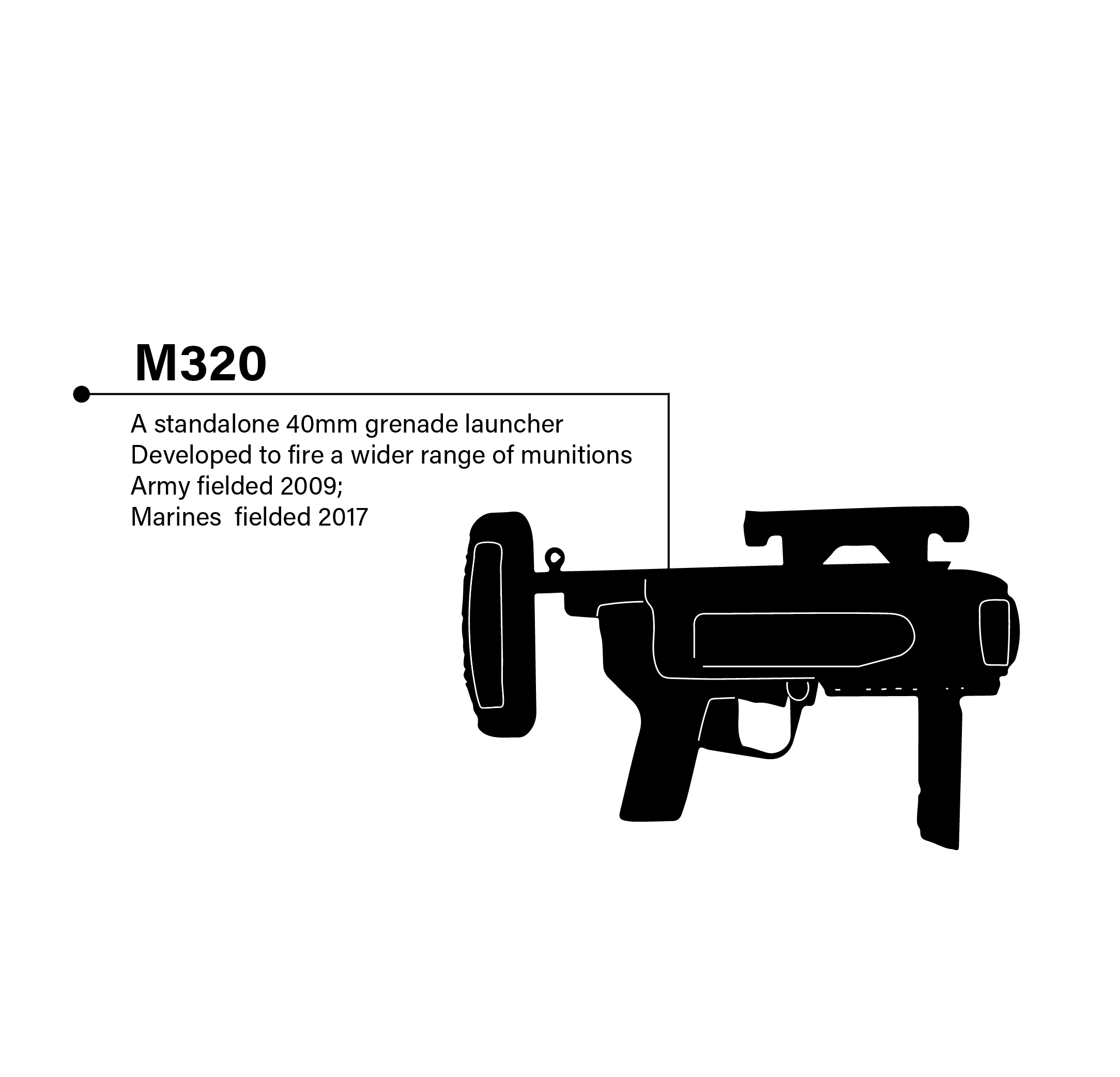

All of which make the M320 a new grenade launcher that can either be mounted below the M16 or as a standalone shooter, a more capable weapon.

Soldiers may benefit from work being done on the special operations forces side as well. SOF weapons developers will conduct technical evaluations of a .338 Norma Magnum machine gun this year and the same evaluations are planned for a 6.5 Creedmoor machine gun, both aimed at increasing range and lethality.

The pistol

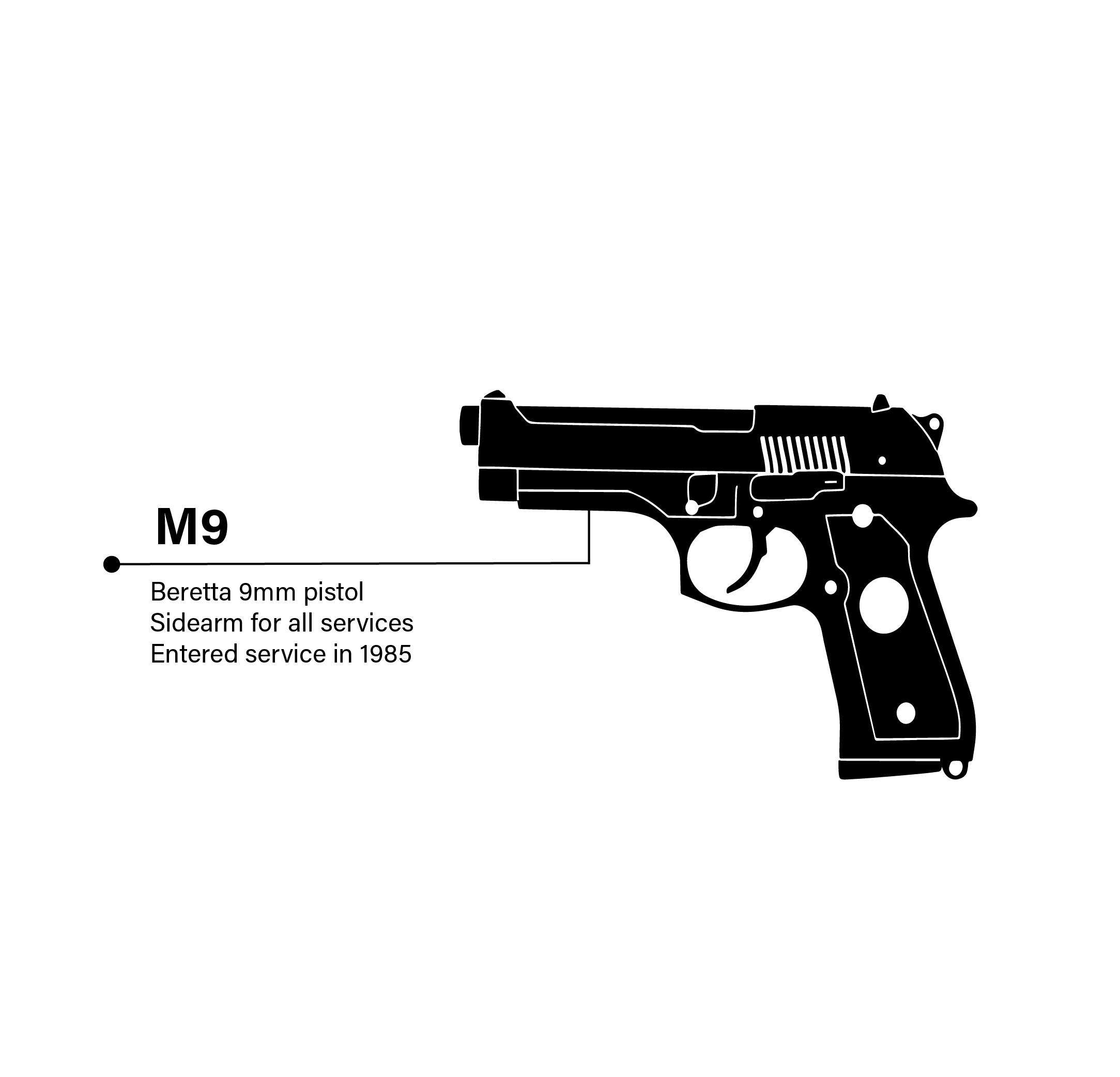

One of the fastest changes seen in small arms history for a service-wide adoption might have been the fielding of the modular handgun system, which contains the M17 and M18 handgun variants. The M17 is the full-sized, standard issue sidearm to replace the M9 Beretta. The M18 is the compact version, typically used by Army investigators or those whose duty may require a concealed pistol.

In a two-year timeframe the Army sought the pistol replacement and began fielding the new weapon.

That move was a far cry from past efforts, such as the Future Handgun System, the Joint Combat Pistol and the Combat Pistol Program, all of which predated this effort but didn’t result in a replacement for the M9 Beretta 9mm pistol, which was first fielded in 1985.

RELATED

The new handgun, made by Sig Sauer, provides soldiers with a built-in rail system and top mounted optics option and suppressor-ready barrel.

The current M9 required major modifications to have any of those capabilities.

The MHS also looks at the sidearm as part of a larger weapon system; one that includes a holster, suppressor and laser aiming device, rather than simply a handgun.

That move, Army Times reported, was one piece of larger efforts to improve small arms more rapidly for the general purpose Army.

Small changes, major payoff

The incremental work of some programs might not jump out the way a futuristic rifle or new pistol but little changes add up.

For example, changes include advances to the M4 carbine. Now in its A1 version, the standard issue weapon sports an ambidextrous selector switch and improved barrel.

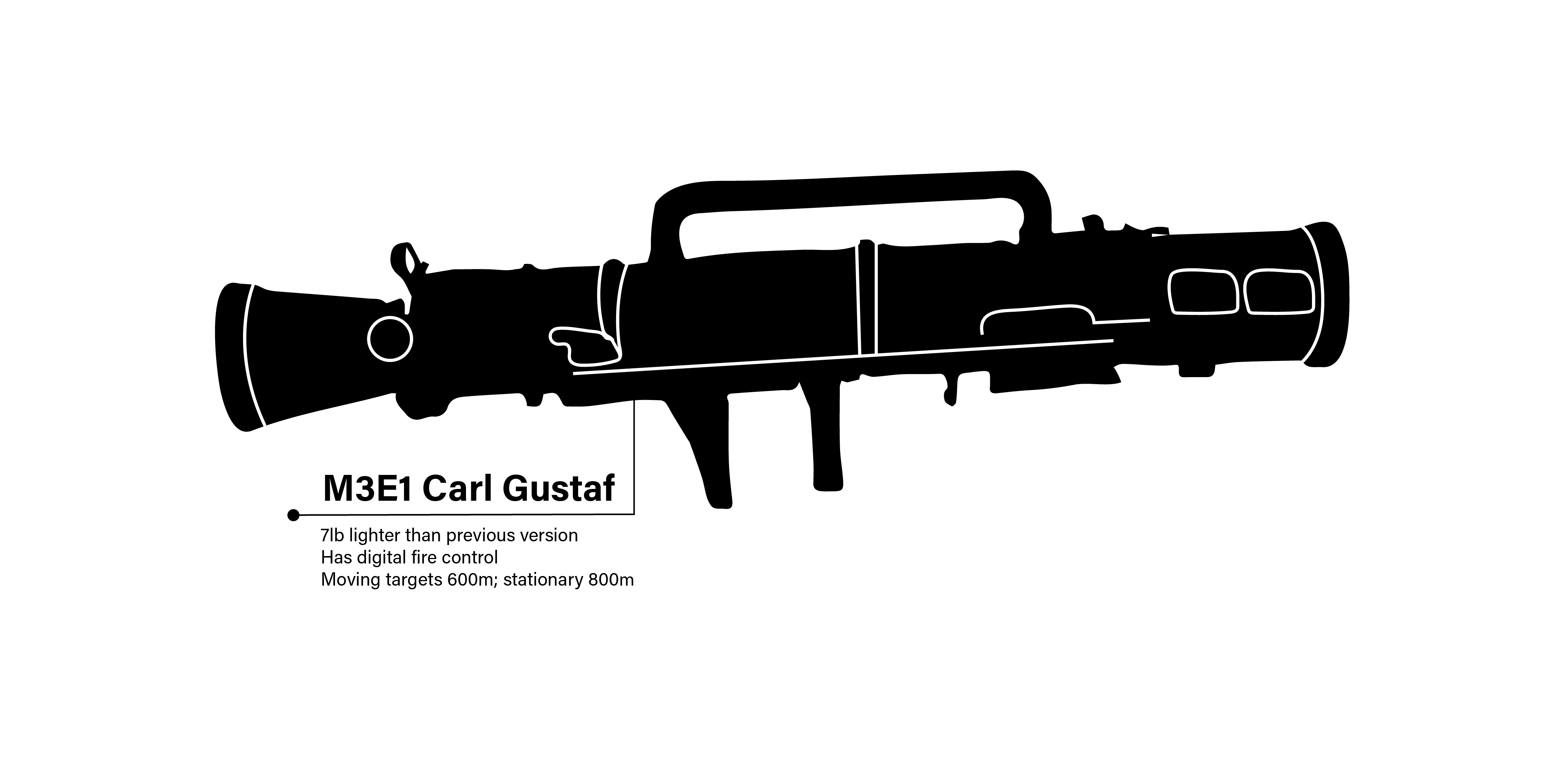

The Carl Gustaf, an 84mm recoilless rifle is undergoing its own upgrades since the Army adopted it nearly six years ago. The newer version is 7lbs. lighter, uses titanium and has a digital fire control compared to the old mechanical versions.

Those changes allow it to consistently hit moving targets out to 600 meters and strike stationary targets at 800 meters.

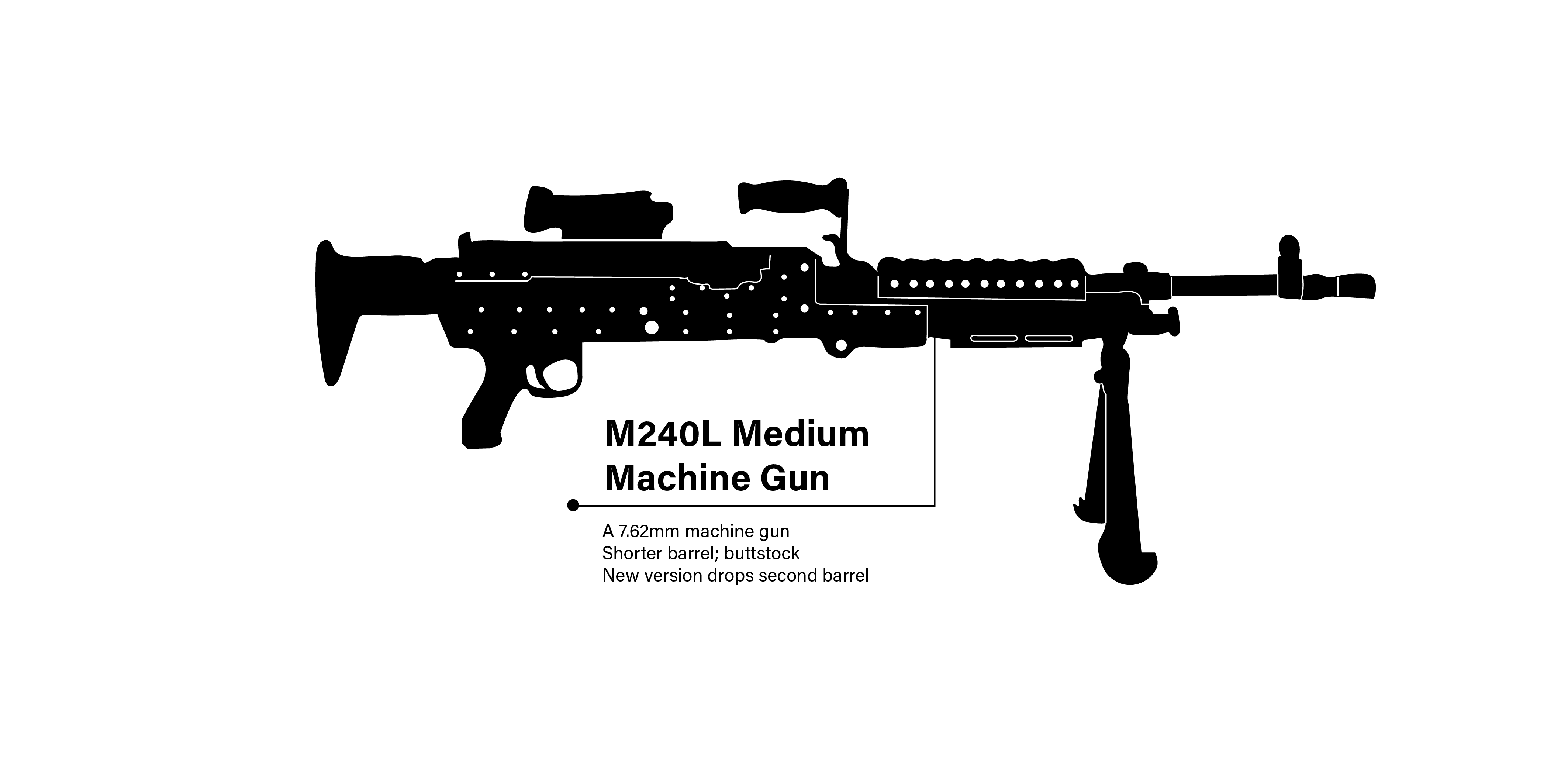

The M240 machine gun, the base of medium-machine gun fire for the Army since the late 1970s, is seeing improvements that will take some weight off of both the machine gunner and the assistant machine gunner.

Better materials and technology have allowed for the weapon to cut the spare barrel and shorten the buttstock and barrel.

The program also selected new optics for the M240, Mk 19 automatic grenade launcher and M2A1 .50 caliber machine gun this year.

How it happens, what it means

The beginnings of much of what’s changed has come from seasoned combat veterans and experts in weaponry and lethality at both the Maneuver Center of Excellence and the newer addition of the Soldier Lethality Cross Functional Team.

Once those groups set what the Army needs, its then up to the Program Executive Office Soldier weapons entities to bring it to life.

In just the past year, they’ve fielded more than 135,000 weapons across the Army. That’s a piece of the larger 1.2 million weapons they’ve fielded for all four service branches since 2003, said Col. Elliott Caggins, program manager for soldier lethality.

A combination of battlefield feedback and anticipated adversary threats fuel how the researchers tackle improving small arms.

Some of that feedback includes a 2006 CNA Corporation report, “Soldier Perspectives on Small Arms in Combat.”

That study showed that soldiers gave poor marks to the squad automatic weapon and M9 pistol. Both of which have been or are being replaced.

Those include a host of items, from problems with legacy weapons systems to needs to extend range or increase durability to intelligence showing that adversaries such as Russia, China or even extremist organizations are switching to longer-range, heavier calibers that outmatch the soldier’s service weapon.

While operational needs and feedback from the field inform what changes they’ll make, newer weapons, lighter options and more ways to deliver rounds down range also open ways in which the Army can re-examine how it uses the squad.

With greater ranges and ways to engage, the squad’s reach and effectiveness also evolve.

But how the Army is tackling the never-ending problem of providing state of the art weapons to soldiers at the lowest tactical level uses both methods to identify where to go with weapons development.

“We’re able to do both, either make changes or develop opportunities,” Caggins said.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.