The Green Berets woke up at 2 a.m. on April 6, 2008, to take an early look at the target area.

Cold, snow-capped and perched at more than 10,000 feet, the objective wasn’t ideal. But intelligence said a high-value target aligned with the Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin insurgent group was up there.

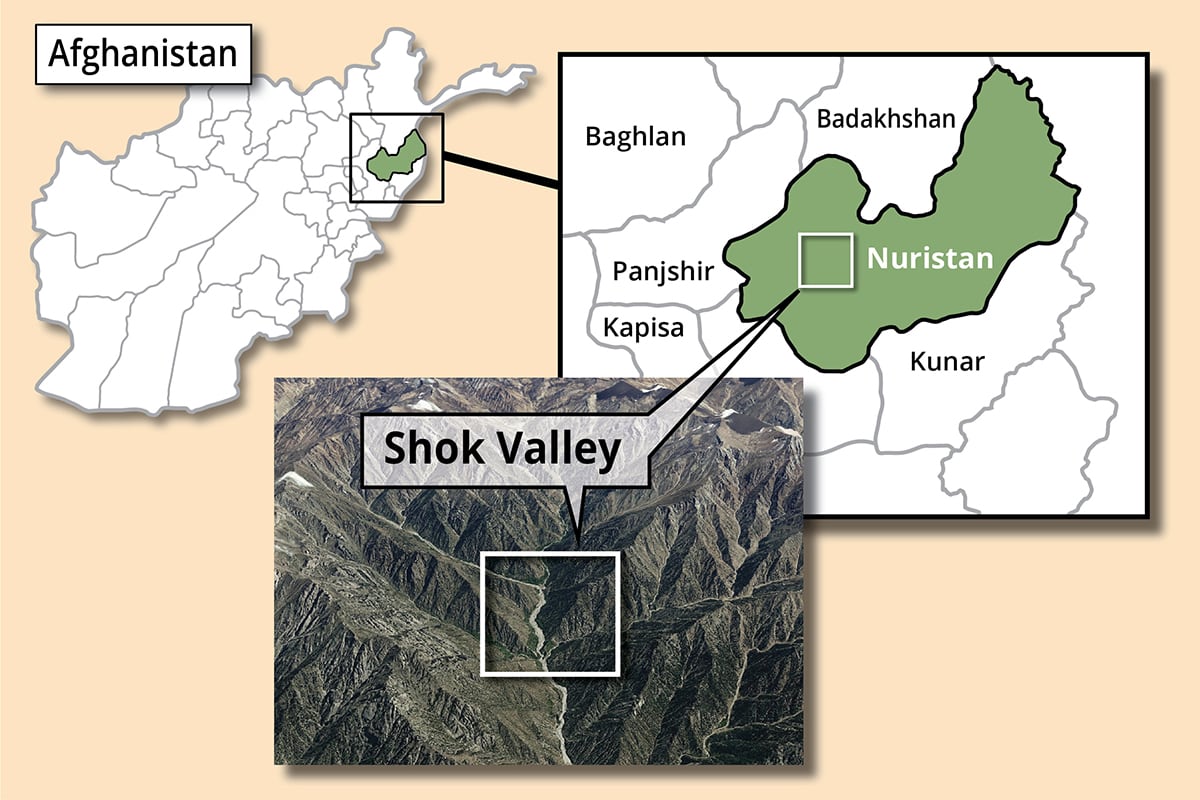

By the time they were hovering over Nuristan province’s Shok Valley in CH-47 Chinook helicopters, it was clear that Operational Detachment Alpha 3336 wasn’t going to be landing.

“It was just a little more treacherous than we thought,” said Master Sgt. Matthew O. Williams, the ODA’s weapons sergeant who will receive the Medal of Honor on Wednesday for his actions during the 2008 mission.

The jagged terrain and sheer cliffs were too steep for the Chinooks, so ODA 3336 and their Afghan National Army Commandos jumped into a fast-moving, waist-deep river running through the target.

“The helicopters could not land," said Lt. Col. Kyle Walton, the ODA commander. “We had to jump, sometimes into the river, sometimes into jagged rocks about 10-12 feet off the back end of the helicopter — and that was at the beginning of the mission.”

The team set out up the steep terrain. A heavy weapons section composed of Afghan Commandos moved alongside Williams.

It became clear early on that the enemy force was much stronger than anticipated. Just as they ascended to the target, machine guns, sniper fire and rocket-propelled grenades began to rain down.

The command and control element and the lead assault force were quickly pinned down by heavy fire from the high-value target’s militia, known as Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin, or HiG.

The coalition forces immediately took casualties, including their interpreter, who was killed in the opening salvo. “Everybody else was hit by enemy fire or actually wounded by enemy fire,” Walton recalled.

“In short order, we found ourselves bounding back to an approximately 100-foot cliff where we were forced to fight for the next seven hours for survival and levy close air support almost directly on top of our positions," Walton added.

The pinned down force was in danger of being overrun. Staff Sgt. Ronald J. Shurer II, the Green Beret medic who received the Medal of Honor for the same battle last year, and retired Green Beret Master Sgt. Scott Ford, the senior NCO, set out to recover the casualties.

“They needed assistance, so Ron and Scott, they led the charge,” Williams said.

Williams followed with his Afghan Commandos to provide security and put more guns between the wounded friendlies and the enemy HiG fighters.

They bounded up the mountainside and began laying down suppressive fire. As they did so, Ford was hit by a sniper’s round.

Williams then exposed himself to enemy fire to render aid to Ford and move him down the mountainside to a casualty collection point set up inside a little house lower in the valley.

“Our focus at that point really changed," Williams recalled, adding that it was no longer tactically sound to continue the mission.

“These guys needed to get off the mountain one way or another," he said.

Williams once again braved small arms fire as he climbed back up the cliff to evacuate other injured soldiers and repair the team’s satellite radio, according to his award citation. He then helped move several more casualties down the nearly vertical mountainside.

At one point during the seven-hour gunfight, Williams led a counterattack with his Afghan Commandos to repel the HiG fighters from the casualty collection point.

His Medal of Honor citation states that Williams’ actions helped save the lives of four critically wounded soldiers and prevented the lead element of the assault force from being overrun.

Throughout the ordeal, about 70 danger-close airstrikes were called in by the team’s Air Force Special Tactics combat controller, now-retired Master Sgt. Zachary Rhyner.

“The [close-air support] is for sure a reason why we are all sitting here today, and Zach’s ability to harness his training and get them on target quickly really speaks to that," Williams said.

The team held their ground at the casualty collection point while helicopters came in to ferry out the wounded. The pilots and aircrews took fire throughout the extraction.

The Afghan partner force was also instrumental in the fight, Ford told reporters at the Pentagon on Tuesday.

This deployment was the first formal train, equip and accompany mission with the Afghan Commandos Corps — a cohort that would be instrumental in pushing back against insurgent groups for years to come.

“They were eager to start laying down suppressive fire,” Williams said. “They stuck with us as best they could and they really relied on the trust we built together through the months of training that led up to that mission. ... They understood we were there 'til the end and we weren’t just going to bail out and leave them and they did their best to reciprocate.”

There were about 100 Afghan Commandos throughout the battlefield that day.

“We were always partnered throughout the war up until that point," Ford said. “However, I think the distinct emphasis on this trip is we had stood up the first battalion of Commandos — a Ranger-type battalion of men that were going to be Afghanistan’s future."

“It was a big step for, I think, the theater and the country of Afghanistan," Ford added.

The U.S. military claims that more than 150 insurgents were killed during the seven-hour battle.

The team continued to receive intelligence indications that the high value target was in Shok Valley throughout the battle, Walton said.

“There was confusion at first as to whether or not he had been killed in the airstrikes or the assault on the objective,” Walton explained.

HiG’s leader, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, certainly wasn’t killed that day, though he was likely present. Hekmatyar continued to lead the militant group until around 2016, when a peace deal and a pardon allowed the paramilitary commander a spot in Afghan politics, where he remains today.

Being a target of U.S. special operations forces and Afghan Commandos may have helped drive him to reconciliation.

“It doesn’t really matter to me," Williams said. "We’re told who the enemy is and then we pursue the enemy. If diplomatically things change, then things change and that’s fine.”

Kyle Rempfer was an editor and reporter who has covered combat operations, criminal cases, foreign military assistance and training accidents. Before entering journalism, Kyle served in U.S. Air Force Special Tactics and deployed in 2014 to Paktika Province, Afghanistan, and Baghdad, Iraq.