The Army has launched an inquiry into the circumstances that led a 19-year-old on anxiety medication who was diagnosed with autism and congenital arm disorders to report for basic combat training at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, this August.

The young man’s father told Army Times that he has been trying to help return his son to their hometown in Idaho by reaching out to service officials and congressional representatives. After his son reported for basic training on Aug. 20, he began having anxiety attacks and was quickly separated from his basic training unit to be out-processed for not disclosing his myriad of diagnosed disorders.

Both the father and son say that his Army recruiter encouraged him to hide potentially disqualifying factors in order to enlist as a human resources specialist.

“U.S. Army Recruiting Command has initiated an inquiry into this situation, and appropriate action will be taken when all facts are known,” Lisa Ferguson, the chief spokeswoman for the service’s recruiting command, told Army Times.

Army applicants with autism spectrum disorders are automatically disqualified, per Defense Department accession policy, though sometimes medical enlistment waivers are granted after a visit to a DoD behavioral health consultant, according to Ferguson.

“All waivers are considered on a case-by-case basis, but generally speaking, autism isn’t something normally waived if the diagnosis was appropriately given,” Ferguson said.

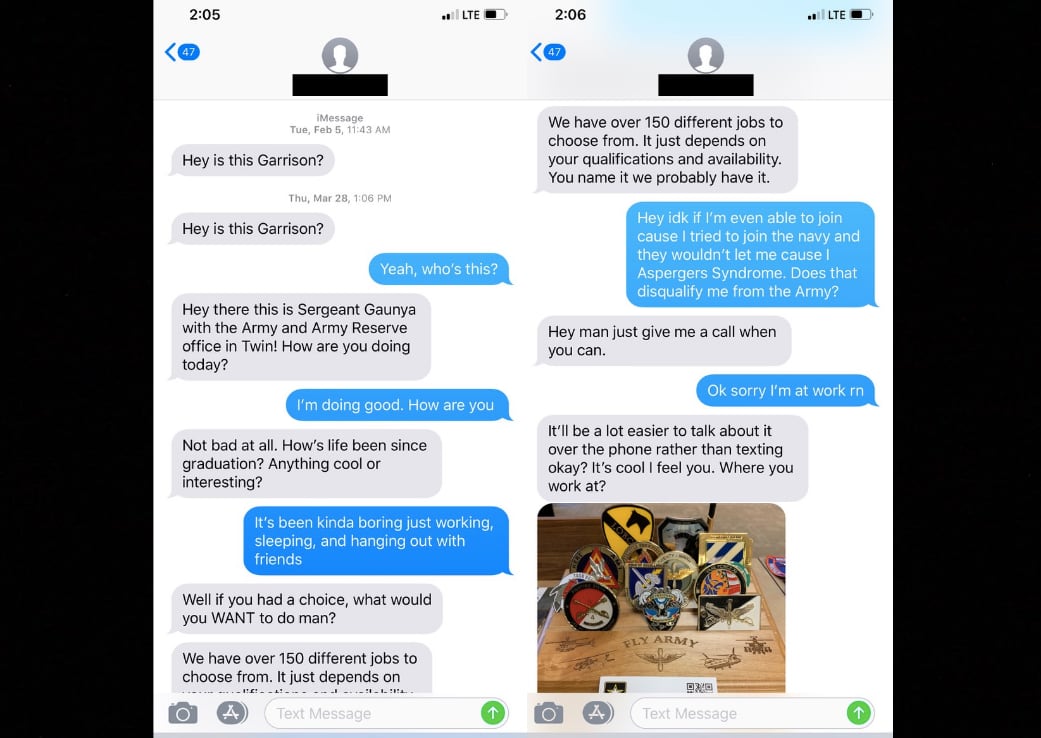

After being turned down by Navy recruiters over his autism diagnosis, which dates back to 2011, Garrison Horsley was contacted by an Army recruiter out of Twin Falls, Idaho.

Horsley warned the recruiter, Staff Sgt. Jeffrey Gaunya, that he was previously unable to enlist and said that he had high-functioning autism in a series of text messages provided to Army Times. But the recruiter encouraged Horsley to call him rather than text further, Horsley said in a phone interview given while he waits as a hold-over at Fort Jackson.

Gaunya did not respond to Army Times’ request for comment. His unit, the Salt Lake City Recruiting Battalion, declined to comment.

“He knew all about it [the autism diagnosis] and he just said that ‘the Army only knows what you tell them,’ ” Horsley said.

Horsley added that he never disclosed his diagnosis or anxiety medication during his visits to Military Entrance Processing Command, and the doctors never brought it up, even though it was documented in his civilian medical records.

Ryan Horsley, Garrison Horsley’s father, said that he “disagreed and was afraid” with the enlistment prospect, but didn’t imagine his son would be able to complete the medical screening process.

“I said ‘you’re not going to clear medical because of the autism. Not only that, but your left arm doesn’t work. How are you going to get through push-ups and pull-ups.' He can’t fully rotate his left arm,” the father said.

Prior to enlisting, Horsley had been seeing physical therapists to treat a case of radioulnar synostosis in his left arm, a congenital condition that limits movement and has made it difficult for him to exercise.

“My left arm is 50 percent weaker than my right, but I got a waiver for that,” Horsley said. “I’ve never been able to do a pull-up in my life and I max out on push-ups at 15 or 10. I can’t turn my hand palm up.”

An Aug. 30 memo signed by Horsley’s primary care physician states that the young man was being treated for a mild episode of recurrent depressive disorder, in addition to the autism diagnosis, as part of his current medical issues.

“We have extensive screening requirements recruiters must follow throughout the applicant process. Recruiter impropriety is unacceptable," Ferguson said, while not stating whether or not the recruiter in this case violated any policies. "USAREC has a Recruiting Standards Directorate to ensure the processes are carried out thoroughly and completely. Recruiters are expected to be transparent and honest as we seek to find fully qualified, quality candidates to protect our nation.”

It wasn’t until the “moment of truth” — a final opportunity for recruits to confess to infractions they may have omitted during the enlistment process — that Horsley said he told officials that he was having anxiety attacks.

“They were just yelling and I was panicking," he said. “When we went to the moment of truth, I told them I have anxiety and they just kind of laughed in my face.”

Horsley was also supposed to be taking a prescription for daily 20mg doses of Citalopram, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, or SSRI, though he admitted to routinely lapsing on doses.

SSRI medications may be taken for a range of issues, including anxiety, migraine prevention and even pelvic pain. Enlistment waivers can be considered on a case-by-case basis, depending on the condition being treated, Ferguson said.

However, DoD policy states that depressive disorder symptoms and treatment within the last 36 months are disqualifying.

Horsley did sign paperwork stating that there was nothing wrong with him during the enlistment process, but he maintains that this is what his recruiter instructed him to do, advising Horsley that the more boxes you check, the more reasons you’re giving the Army to reject you, he said.

For each disorder, Horsley reported back to his dad that recruiters told him it wouldn’t be an issue because he could obtain a waiver or basic training isn’t as stressful as it used to be.

“Three weeks before I left, my recruiter went on leave and didn’t tell me," Horsley added. "He didn’t text or anything and then he unfriended me on Facebook.”

Horsley’s father said that he regretted not being more assertive in pushing back against his son enlisting.

“It was a tough area to balance because I wanted to show that I supported him in his decision,” Ryan Horsley said. “Obviously I should have been more vocal but I could not understand why they were allowing it to proceed. I even started questioning as well whether he actually told him, but then I saw that he did [in the text messages].”

At this point, it doesn’t appear as if Horsley will be punished for enlisting without disclosing his conditions, the father said.

“I think those texts establish that he informed them," the father added. "And according to [Garrison Horsley], his recruiter kept telling him about his medical conditions that ‘the Army does not need to know,’ which is contrary to what I had been telling him because I wanted him to disclose the conditions so he would be disqualified.”

Kyle Rempfer was an editor and reporter who has covered combat operations, criminal cases, foreign military assistance and training accidents. Before entering journalism, Kyle served in U.S. Air Force Special Tactics and deployed in 2014 to Paktika Province, Afghanistan, and Baghdad, Iraq.