At a veteran’s home in Louisiana’s bayou country, the French Legion of Honor has been bestowed upon an aptly named World War II veteran, Pfc. Lawrence Boudreaux, by the new French Ambassador who recently made a special trip there.

Boudreaux tells of participating in the invasion of Normandy in a strafed landing craft that was possibly made in Louisiana, how he was towed across the Dutch skies by a C-47 in a canvas-and-plywood glider and seated in a Jeep ready to roll out when the expendable glider hit the ground, and later still, liberating French Champagne from the cellars at Hitler’s second home.

“Hitler had stolen it from the French,” reasons Boudreaux. “So, we took it back. It was pretty good Champagne too.”

He chuckled as he recounted how the Screaming Eagles went down to the Third Reich’s cellars and took the Champagne and a lot more back home. He referred to it as soldiers collecting souvenirs.

As part of the whirlwind media blitz Boudreaux, 97, is experiencing for the first time in his life, he shared anecdotes from his war experiences with Army Times.

Found: Lost member of the 321st Glider Field Artillery Battalion

Boudreaux is likely one of only two remaining “Screaming Eagles” glidermen, said G.J. Dettore, author of “Screaming Eagle Gliders: The 321st Glider Field Artillery Battalion of the 101st Airborne Division in World War II."

Dettore researched the battalion and attempted to track down any survivors in what he refers to as a research project extraordinaire using the battalion’s rosters for more than 21 years before writing his book.

“As far I know there’s only two left of the 321st glidermen," said Dettore. “Pfc. Elmo Smiley of Michigan is the other member of the 321st still living. I thought he was it, but now we have Boudreaux down in Louisiana."

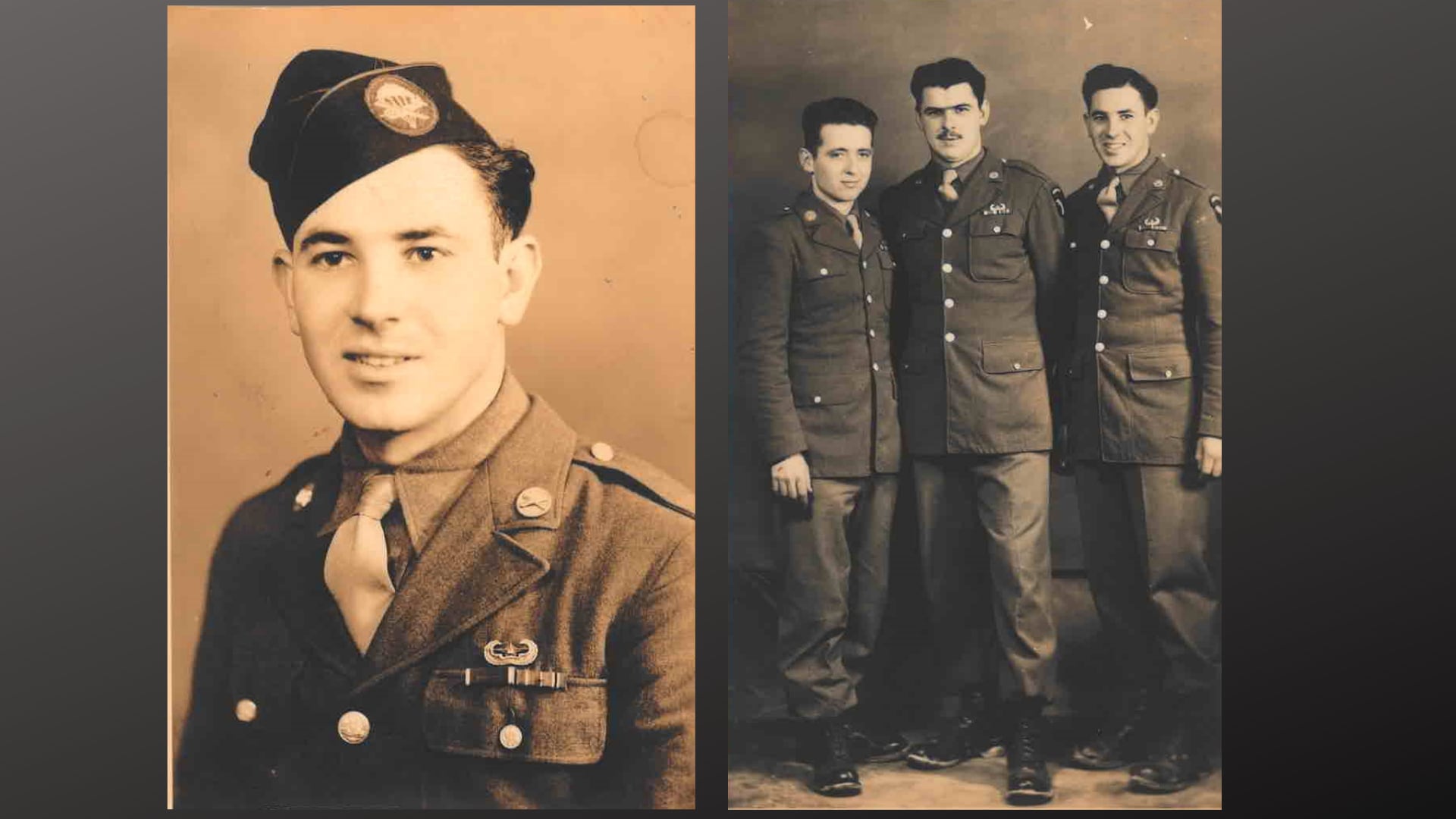

Dettore’s book features several photos of Boudreaux that were not identified. However, one photo mentions his name in the caption as “Larry,” a name he says he has never used. In the other photos, his image remains unlabeled as no one knew the identity of the unknown soldier in the photographs. Now they will.

After Boudreaux was given a copy of Dettore’s book by his daughter a few years back — she says he didn’t put it down for weeks — and as he read, he marked with arrows all the photographs that featured him.

After decades of research into the 321st and attempting to track down the remaining members of the unit, Dettore was surprised to learn that Boudreaux was alive and still living in Louisiana.

The oral history department of the National World War II Museum in New Orleans, when contacted, also said they have had no contact with a living member of the 321st since before 2006.

Boudreaux’s personal war stories, which had been lost to historians for decades, are now being shared in his jaunty Cajun accent.

His tale begins at the age of 20 when he was inducted into the Army from the small Acadiana town of Church Point, Louisiana on Feb, 9, 1943. It then unfolds with adventures that could easily fill several Hollywood movies.

The 321st

Boudreaux’s World War II journey began after basic training at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. It was there that he was selected for the 101st Airborne Division’s elite 321st “Screaming Eagle” Glider Field Artillery Battalion. Coincidentally, the 101st Airborne Division had been re-activated a year earlier at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana, only an hour from his hometown.

His first posting overseas was to a small, converted stable block on Whatcombe Farms in rural Berkshire, England in September 1943. This is where the 321st Glider Field Artillery Battalion would secretly drill and be trained for the allied invasion of Europe. He says he believes the posting was due to his ability to speak French as his first language.

According to 321st gun section personnel assignment documents that Dettore referenced, Boudreaux was assigned to Battery B or “Baker” in the 4th gun section.

"Each battery had six 75mm howitzers," said Dettore. "The 321st had a total of six gun sections."

Boudreaux’s assignment was to fight Germans by dropping out of the sky in a break-away Waco CG-4A glider — in a Jeep towing a rolling howitzer. Boudreaux says he was a “load man” who loaded ammunition and set targets.

While waiting in the English countryside for his war to begin, any spare time was spent dancing and gambling.

Boudreaux says he and his friends visited the local pubs where they purchased dinners for the English girls in a barter exchange for a dance partner for the night. He remembers that the beer was good, but to a Cajun boy, the food was awful. He recounts how one girl he befriended wrote to him after the war to see if he’d survived, they checked up on each other for a while to see that they had both made it through alive.

The invasion of Normandy

When the Allied invasion of western Europe finally came, despite the endless glider drills which his Airborne unit had practiced at Whatcombe, the 321st arrived by sea.

Boudreaux’s memories of the invasion of Normandy began in the English Channel.

"They put us on a ship across the Channel (the Liberty ship SS John Mosby),” said Boudreaux. “Then on June 9, 1944, we moved onto a landing craft and we landed on Utah beach.”

Due to operational confusion, the SS Mosby would sit in the sea waiting to be unloaded for several days in which it was repeatedly strafed by German aircraft. Then, after his unit finally transferred to their landing craft, they were hit again.

The landing craft was hit by friendly fire aimed at German aircraft, Dettore said.

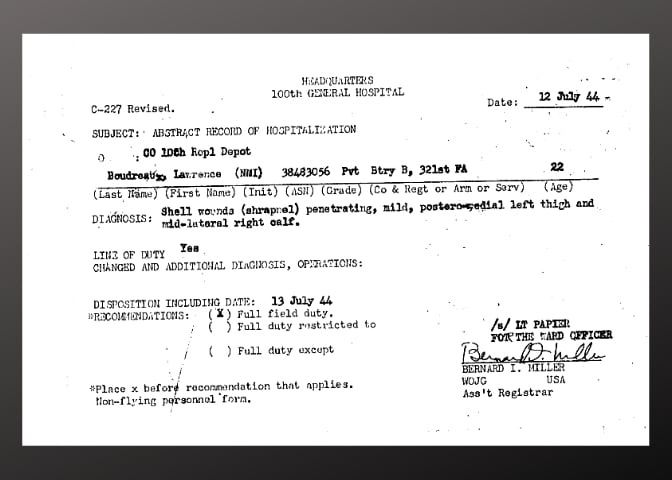

“We were fixing to land, and I was hit by shells inside the boat,” said Boudreaux. “I was one of the fifteen of us onboard who were injured, six of the injured stayed on to fight with the battalion, and nine of us went back to England. I was one of the nine.”

Boudreaux says that after he was hit in the leg twice, he dove under a Jeep trailer.

"A 'friendly' round among thousands came down, hitting the floor of the landing craft," said Dettore, based on research. "It knocked the men down like bowling pins."

Boudreaux says he was hospitalized in England for about 30 days, then discharged, and sent back to his unit.

Operation Market Garden

Boudreaux and the 321st’s next mission was Operation Market Garden in the Netherlands.

He explains that their objective was to secure the bridges in Holland, thus allowing passage for Allied troops to enter the Rhineland.

“After I was wounded in France, my division, the 321st came back to Whatcombe, but by then, the 101st were scattered all over England, the gliders, infantry and the paratroopers,” said Boudreaux. “We were at the farm again training and waiting for our next mission.”

They would arrive from the air this time — but without parachutes. They would be tugged by nylon rope behind C-47 transports in gliders the unit had nicknamed “flying coffins.”

After a year of training, they took off from England in what became known as the largest air invasion in history.

“Our mission came on September 19, 1944,” said Boudreaux. “We had to go behind enemy lines to secure some bridges before the enemy got there.”

“We had a Jeep strapped in our glider. I was sitting on the passenger side, the Jeep driver was sitting at the wheel. Another guy in the battalion sat up front in the co-pilot’s seat next to the pilot because there was no co-pilot.”

“We landed behind enemy lines near Eindhoven in Holland. We were lucky, we made a good landing, but then some didn’t. Some crashed, I remember boys crying out when they hit the ground. Some gliders were shot down and some like us landed behind enemy lines.”

What ensued was what Boudreaux described as 73 days of heavy fighting on the front line against the Germans.

France, Ardennes and the Battle of the Bulge

Afterward, Boudreaux recalled that they were off to a new base camp in France and leave time. He said the food was sparse but excellent, even if it was just an egg sandwich, he says the French knew how to cook.

The battalion’s leave and what Boudreaux refers to as the “Great Rest” took place at the tiny French village of Mourmelon-le-Petit, France. Boudreaux reminisced about beer, dancing with the local girls, and a short celebration before they were abruptly called back to the war.

“We were having a good time and dancing, and going to the bars,” said Boudreaux.

Dettore explains that the men were there for new clothing and equipment as what they had was either worn or depleted. Boudreaux says they were waiting to celebrate Christmas in the village. However, the unit was called back to action earlier than planned when the Germans broke the line.

Boudreaux remembers that after only three weeks the unit was quickly loaded into large trucks heading towards Ardennes and Bastogne to fight in that would become known as the Battle of the Bulge.

“They put us in trucks, 18-wheelers, and jeeps, and we traveled by convoy," said Boudreaux.

Dettore says they were never given the time to be re-outfitted and left wearing still-tattered clothing on Dec. 18, 1944.

“When we got to Bastogne, we set up there and met the enemy, then we were surrounded by eight German divisions for six days, until the day before Christmas,” said Boudreaux. “Then General Patton came through and broke the line."

He says they stayed in Bastogne another 30 days after Patton arrived.

The Eagle’s Nest

Boudreaux recounted his unit’s march into the mountains of the Rhineland to meet the enemy and secure Hitler and the Third Reich’s retreat in the Bavarian Alps in May 1945. But, he says, the Germans were gone when they arrived.

“Later, after Patton, they figured the Germans would attack near Alsace, France, but they didn’t,” said Boudreaux. "They were holding down near the small village of Berchtesgaden near Hitler’s second home, the Eagle’s Nest, so we were sent there next.”

The 321st enjoyed their post V-E Day victory in Berchtesgaden. Boudreaux laughed as he recalled the 321st drinking the spoils of war from what he referred to as Hitler’s sporting lodge.

“The Eagle’s Nest was Hitler’s second home, they had bombed the place from the air, it was torn up,” said Boudreaux. “We went inside there looking around and we started what we called ‘collecting a few souvenirs’.”

"They had wine and all kind of liquor in the hidden cellars,” Boudreaux said. “We came back with a sack full. There was wine, Cognac, and Champagne that Hitler had stolen from the French.”

Boudreaux also gathered pieces of the silver service, including a tea pot, sugar bowl, oval serving dishes, and tray from the Platterhof Hotel.

Boudreaux mailed the silver back home to his mother, who used it for years at table in their family farm house in Pine Island, Louisiana.

Legion d’Honneur

Now, 75 years later, after a quiet life as a small town police chief and retirement, his long-ago wartime service has come back to him.

His daughter Barbara Broussard researched honors given in thanks to World War II veterans and realizing her father qualified, she investigated and completed the application for him.

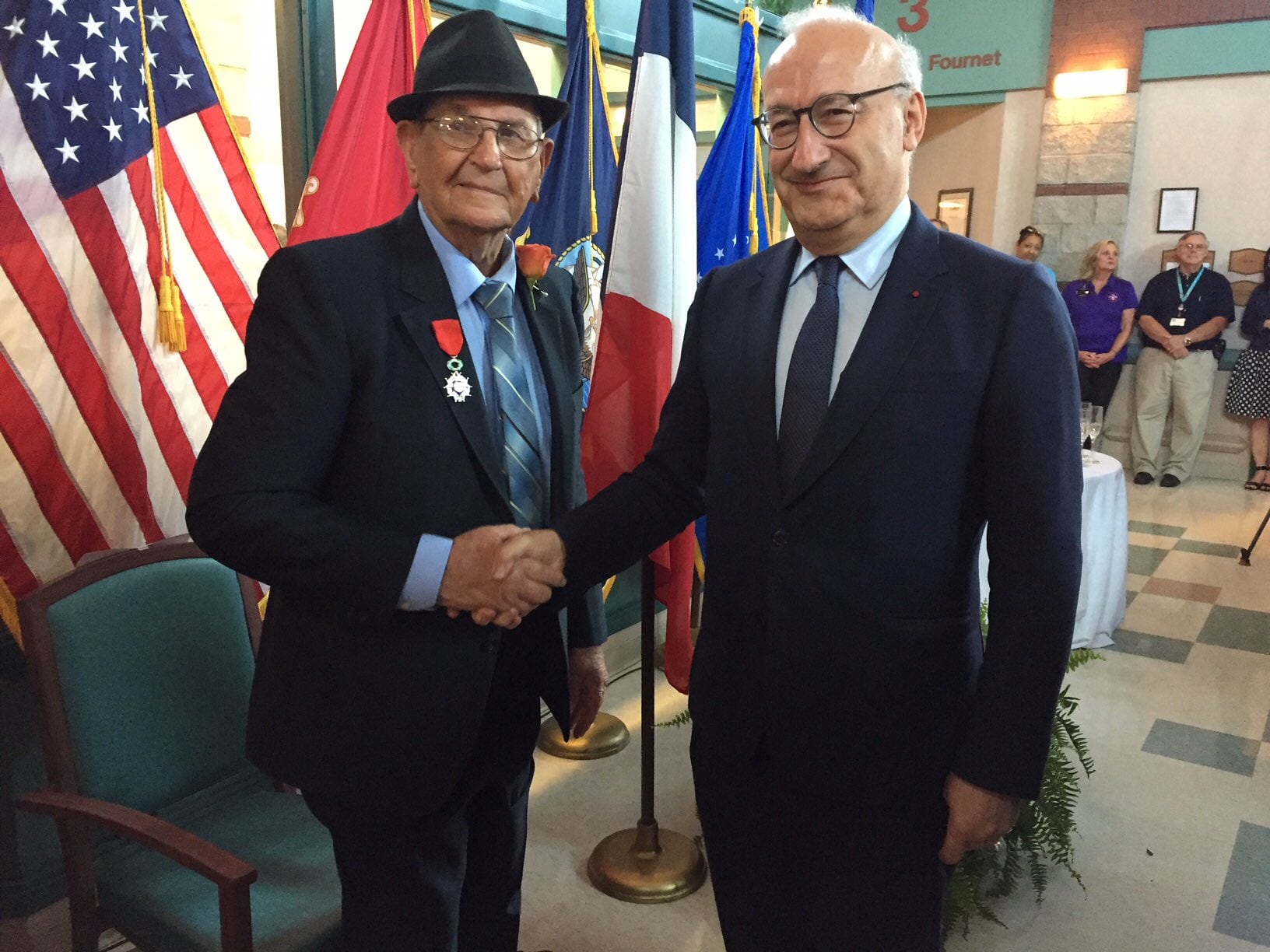

On July 16, in the year of the 75th anniversary of the invasion of Normandy, the French ambassador to the United States, Philippe Étienne, made the long journey to a small veteran’s home in rural Louisiana to deliver France’s highest distinction, the Legion d’Honneur and to bestow its accompanying knighthood.

The Order of Merit is awarded to U.S. veterans who risked their life during World War II to fight on French territory. Étienne says France wanted to pay tribute to Boudreaux and to “all American veterans who liberated France and Europe.”

“You are a man of courage,” said Étienne to Boudreaux in front of the crowd that gathered during the ceremony at the veteran’s home. “On behalf of the people of France, I offer you our eternal gratitude and our most sincere appreciation for your service.”

The week after he received his award from the ambassador, Boudreaux also received a visit and a state award from John Bel Edwards, the governor of Louisiana.

A humble Boudreaux demurs

“When I found out I was receiving this award, it did not seem real,” said Boudreaux. “I told everyone I saw. I called my family and friends. Later on, I thought to myself, why do I get it and others do not?

“In a way, I don’t feel deserving of this medal,” said Boudreaux to the media at his award ceremony, as reported by the VA. “However, I am very proud to be receiving it. I just feel like the real heroes are the ones who did not come back home."

In addition to the Legion of Honor, Boudreaux is the recipient of a Purple Heart, a Bronze Star, the Croix de Guerre with palm and the Fourragère 1940 from the Kingdom of Belgium.

His daughters keep and catalog his medals in a glass case and say that it houses two presidential citations, a bronze arrowhead, a European theater of operations medal with four campaign stars, a victory medal, an enlisted airborne patch, glider insignia wings, the Louisiana medal and numerous others.

The National World War II Museum in New Orleans has also taken note of the existence of another living member of the 321st and is sending a historian to record his war memories for posterity, when he is ready, says his daughter.

More important to Boudreaux, he says, he is looking forward to a call from 321st author Dettore, a fellow retired police officer. Boudreaux wants to find out what happened to some of his fellow soldiers in the 321st, particularly the wartime friend featured next to him in most of the photographs, Pfc. Gilbert Quinn and his friend Palm.

Until then, Barbara Broussard says her father is happily participating in his bi-weekly poker games at the Southwest Louisiana Veterans Home in Jennings, Louisiana, where he now resides. The same game, along with his favorite games of dice, which he played between missions in the European theater with the 321st, so long ago.