DE PERE, Wis. — You probably did it with a firecracker when you were a kid.

You'd set it on rock or a stump, then you'd light the fuse, clamp your hands over your ears and run, to get out of range of the cardboard shrapnel. Or, if you set it on someone's porch, you ran so as not to get caught.

Well, that's what Mark Bentley of De Pere practiced doing in the U.S. Army, only he did it with atomic bombs: Carry one on your back, plant it somewhere, set the timer, clamp your hands over your ears and run like hell.

“We all knew it was a one-way mission, a suicide mission,” Bentley, who is now 68 and quite probably not even quick enough anymore to outrun firecracker shrapnel, told the Green Bay Press-Gazette.

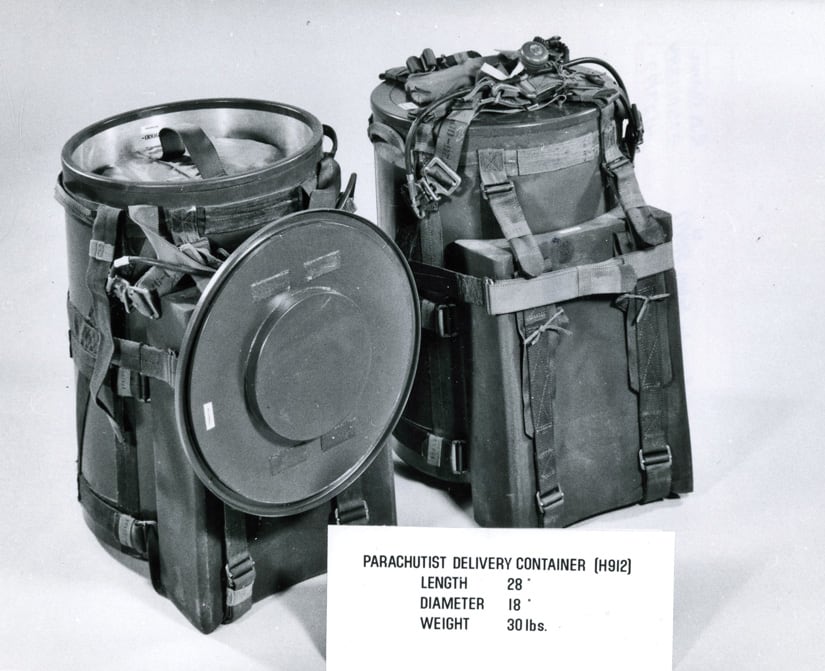

You might not have realized they ever made A-bombs small enough for one man to carry, but they did. They had one called the W54 that fit into a duffel bag. It was less than a tenth as powerful as “Little Boy,” the one dropped on Hiroshima a quarter-century earlier, but without benefit of you being able to fly away in an airplane before it goes off. There was also a bigger one that fit into a 55-gallon drum, two or three times as powerful as the one you could carry on your back, Bentley recalled.

It was part of the post-WWII, Cold War era in which the Soviet Union was viewed as an expansionist threat into western Europe, said John Sharpless, newly retired professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he taught a class on the period.

"The Soviet Union had a substantially larger land army, considerably larger than NATO and the U.S.," Sharpless said. "When you consider the possibility of war in Europe, if the Russians decided to invade from the east, it would be nearly impossible to stop them. So, one strategy was to block various access routes and perhaps funnel them into an area where you could use larger weapons against them."

That was the apparent strategy with the hand-carried nukes, Bentley said — not to nuke Russians directly but rather nuke big holes in the Alps, so that all the resultant ash would fill up the valleys and prevent Soviet tanks and trucks from being able to pass, he said.

The hand-carried nukes evolved out of even smaller nuclear weapons that had been developed in the 1950s, Sharpless said. Those included the Davy Crockett nuclear warheads that could be fired from bazookas and even recoilless rifles, he said.

"The problem was, the blast range was larger than the trajectory," he said.

In other words, you couldn't shoot them far enough to keep yourself out of harm's way. That essentially was the same worry about the hand-carried nuclear mines that Bentley and his fellow soldiers were training to plant: You were unlikely to be able to get out of range yourself.

The funny thing is, Bentley put in for the duty. And no, not because he was suicidal.

The year was 1968, when the Vietnam War was still raging, and Bentley, a new high school graduate, had an alarmingly low draft number.

"It's the only lottery I ever won," said Bentley, who was holding lucky number 27.

RELATED

Enrolling in college, getting married, having a son — none of it staved off the inevitable.

"The question was, do I go in as a draftee and essentially become a target for two years, or do I enlist for three and maybe get to do something I want?" he said.

He decided to enlist. His timing wasn't great; the draft was eliminated just about when he signed the dotted line. But at least the Vietnam War was coming to an end.

He eventually found himself at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, home of the Army engineers. At first, he was trained in a program to deliver acetylene and oxygen to engineers to do repairing and welding in the field. That program was finally deemed unfeasible and he was transferred to one of the Special Atomic Demolition Munition platoons. He recalled he was in one of two such platoons stationed stateside, training, while several others were stationed in central Europe.

Anyway, Bentley never got to the Alps. He kept training and practicing against the possibility of Soviet aggression in Virginia. They took turns carrying a dummy version of the bomb into the woods near the base, setting the timer and imagining the results.

"You constantly trained," he said. "You talk about something being driven through your brain — that's all you ate, slept and thought about eight hours a day."

He got to carry the duffel bag bomb once and set the timer.

"You set your timer, and it would click when it went off, or it went ding or I forget what, but you knew you were toast," he said. "Ding! Your toast is ready, and it's you."

In theory, you could set the timer to give you enough time to flee properly, but somebody would have to stay behind and secure the site, Bentley said.

"The Army is not going to set a bomb like that and run away and leave it, because they don't know if someone else would get ahold of it," he said. "They have to leave troops there to make sure it's not stolen or compromised, and that would just be collateral damage. You didn't go out with the thought that it was anything other than a one-way mission. If you're Bruce Willis, you get away, but I ain't Bruce Willis."

Mercifully, even the platoons stationed near the Alps never got a chance to set off a real one. Maybe the Army decided nukes were better off being dropped from planes, or maybe the threat of attack dwindled as the Cold War was beginning to wind down, Bentley was never sure. But he wasn't surprised.

"I banked on them never doing it," he said.

While actually having to do it would be a scary proposition, merely hanging out in a base not too far from Washington, D.C., and training for it was pretty good duty in Bentley's mind.

"It was a great place to be stationed," he said. "Being a history nut, I had battlefields to visit . . . Jefferson's home at Monticello, Madison's home a couple miles away. We went camping on weekends, at Bull Run. How many people can say they camped at Bull Run, at a national Civil War battlefield?"

Bentley got out in August 1975, a few years before the Special Atomic Demolition Munition units were entirely disbanded. For some reason, he didn't find a lot of civilian employers clamoring to hire someone trained in hand-delivering atomic bombs. His undergraduate degree was in business education, but he quickly learned teaching wasn't for him, so he got a master's degree in personnel and industrial relations and spent most of his working years dealing with union negotiations and other human resources jobs.

“The best thing I ever did was go into the Army,” Bentley said. “You won’t hear many people say that, but you were exposed to so many different ways of life, occupations, places to live, people.”