One year ago, an Army civilian who tossed a water bottle full of gasoline onto his supervisor and lit a match was sentenced by a judge to 20 years in prison for attempted murder.

For the nurse who survived the attack, the fight is not even close to over.

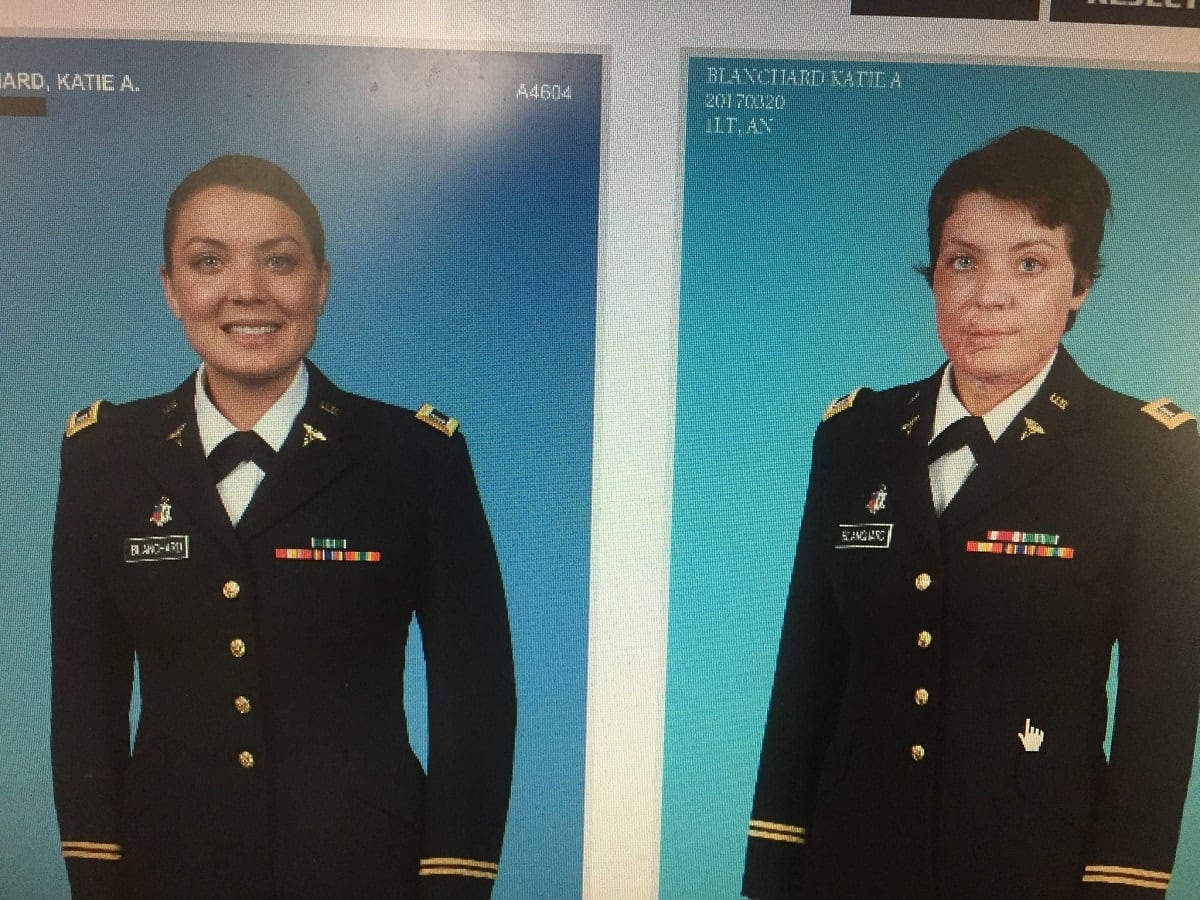

The Feres doctrine prevents service members and their families from suing the Defense Department in the event of injury or death, but for Capt. Katie Blanchard, that is beside the point. In September, she filed a personal injury claim against the Army Combined Arms Center at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where she was working at Munson Army Health Center at the time of the September 2016 assault.

“Is it okay for us to have gross negligence and zero accountability in the military? Because if you look at my case, that’s what it is,” Blanchard told Army Times in a Wednesday phone interview. “Zero accountability for the way they treated me and the things that they missed that will forever affect my life.”

Blanchard, 28, is asking for just under $3.5 million to cover some of the costs of the permanent disabilities she faces, after more than 100 surgeries to date and an intense battle with post-traumatic stress.

She had, for months before the Sept. 7, 2016, attack, warned her supervisors and security personnel at the hospital that she believed Clifford Currie, the civilian employee, would try to kill her. Their relationship had deteriorated over the previous year, as she tried to implement an administrative plan to get his work progress on track.

“I know that I felt really let down when I went to them and told them I didn’t feel safe,” she said. “I thought he would bring a gun in.”

The complaint lists 14 of her superiors and coworkers.

“His anger and disrespect towards me continued to grow until I became scared to be alone with him,” she wrote in the complaint. “He would often curse and yell at me when I would counsel or correct him, which is why I always requested a third party to accompany me when I had to speak with Mr. Currie.”

“As a matter of policy, the Army does not comment on an ongoing matter,” the Army said in a statement to Army Times.

Recovery

Cut to two years later, Blanchard is finishing her master’s degree at the University of Washington, where she is assigned to the Warrior Transition Unit at Joint Base Lewis-McChord.

She is still undergoing surgery every few months for her face, in addition to hundreds of hours working with a speech pathologist (the burns she suffered made it difficult to speak out of both sides of her mouth), physical therapy and occupational therapy.

She’s also had to remodel her home to prevent slipping, help her lift herself up after sitting, reduce the amount of heavy lifting and reaching she has to do, and give her an outdoor space that is protected from the sun.

“People see me and they’re like, ‘Oh, that’s not very bad. You look great,’ ” she said.

The destroyed skin on the upper half of her body was replaced by skin harvested from her lower body, so, in total, most of her body is scarred.

“Just going outside, my skin turns bright purple, and it hurts and burns. I can’t be in the sun. Just stuff like that, that if you had normal skin, you wouldn’t have to worry about,” she said, because it’s tight with scar tissue and easily torn. “My skin is kind of like tissue paper.”

She has at least one, maybe two, surgeries coming up for her hand, and then another on her neck in December.

“Well, it depends on how pretty you want to be,” she joked about how many more procedures she’ll need. “I want to be functional. I want to be able to go camping again with my boys and sleep outside and not be in so much pain that I can’t move the next day.”

While she’s fully insured with Tricare, she said she still fights constantly to get the treatments she needs. She has to fight for a temporary duty order to see specialists they don’t have at JBLM, or to fill a prescription for an extra-strength, non-irritating body moisturizer she applies daily just to be able to comfortably wear clothes and move around.

They kept it stocked at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, she said, where she recovered from the initial attack in their specialized burn unit.

"Here they’re like, ‘Nope, sorry, we don’t provide it,’ " she said. “Well, it’s $20 for a tub of it, and I go through that every three or four days. This is not cosmetic. I don’t like just putting on a ton of lotion every day just to feel pretty.”

She also has orders from a doctor for an orthopedic bed that lifts and reclines, so she can sleep with her head elevated following facial surgery and not risk tremendous swelling.

“That’s for comfort,” was Tricare’s response, she said.

So instead, she sleeps in a recliner in her basement after surgery, keeping herself in position with pillows that shift all night, waking up regularly to rearrange them.

“Yes, you give me medical care, but how much of a fight do I want to do for that?” she said.

The damages she’s seeking from Fort Leavenworth would cover those medical costs that are denied by Tricare, she said, as well as for child care for her sons while she’s in surgery and recovering, and her active duty officer husband isn’t available.

“My husband is currently out in the field and then he’s deploying,” she said.

Moving forward

Blanchard is on active duty for the foreseeable future, she said, but she’s no longer deployable, which is going to be an issue now that the Army is involuntarily separating soldiers after a year out of commission.

“I could fight it,” she said. “But why would I fight your own policy to stay in, after what you guys have done?”

RELATED

She has plans to continue with graduate school once she’s medically retired, she said, to get her Ph.D. in nursing and then go into policy advocacy against workplace violence, her research area.

But why file a claim?

“It was my feeling from the beginning,” she said. “After going through the federal trial and reading through the 15-6 [command investigation]. It was just gross negligence of the command, of the leadership.”

Every bit of her life, from daily tasks to parenting to her nursing career, has been affected by what happened, she said, and though she was not told the details of any administrative or punitive action against her superiors, she said she is certain the Army has not taken steps to rectify what happened to her or prevent it from happening again.

“I want awareness,” she said. “I want people to look at it and take it seriously.”

And she wants the Army to take a hard look at workplace violence, how it trains personnel to deal with issues both for uniformed and civilian staff.

"The solution isn’t a check-the-box, ‘Oh yeah, we put it into our training and we tell them, be nice to each other,' " she said. “How are we making sure that our leaders are open and ready to receive feedback?”

And while the money is not the most important thing, she added, it would be a step toward making it right.

“For me, I feel like the military owes that,” she said. “I’m a young person, and for the rest of my life, I’m going to struggle with this.”

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.