Investigating a botched jump involves a lot of he said, she said.

You might have some footage from the plane or even on the soldier, but witness accounts are about the best you can expect to figure out the cause of an accident.

A team at the Natick Soldier Research, Development and Engineering Center wants to change that by wiring jumps with cameras and sensors for a thorough record of each drop.

“What we realized is that we have all kinds of different inputs for data for jump operations — when they’re doing training drops, they have cameras set up on the drop zone, they might have cameras on the aircraft, some of the jumpers might have cameras on them,” Natick aerospace engineer Sam Corner told Army Times on Aug. 23.

There has also been research measuring shock, force, velocity and other factors through sensors worn during a jump, but those instruments are used on an ad-hoc basis, and leadership has to go through each camera’s feed and each sensor’s calculations individually to review jumps and note any issues.

“What we identified is that there’s really no good way to tie all of this info together,” Corner said, because one would have to try to sync up camera feeds and sensor data to paint a picture. “It’s really a manual process right now.”

Cut to 2016, when his team officially got funding to create a standardized set of cameras, camera locations and instrumentation, as well as a software interface that could process them all automatically.

Some of these things are already available at training centers, he said.

“What could we put on the jumper without significantly interfering with what they’re doing while still giving us the most information?” Corner said.

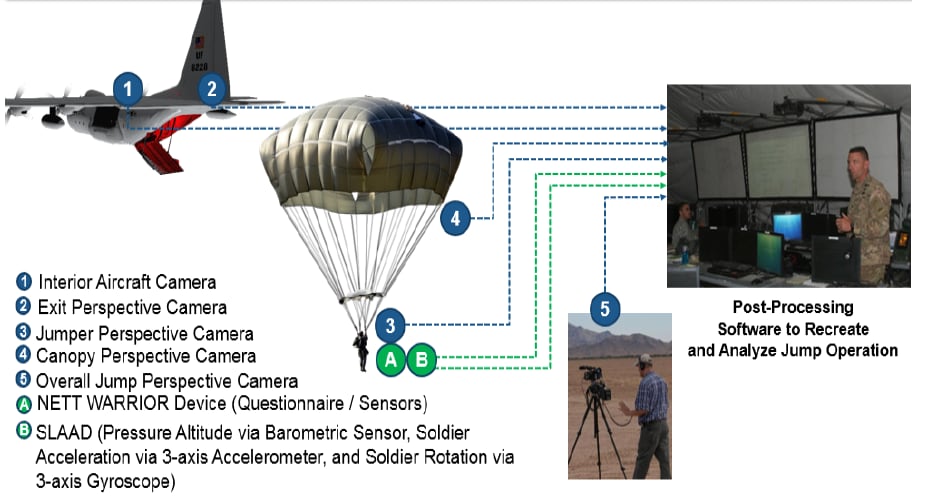

At this point, the team has come up with seven pieces of what will eventually become the Parachute Suite of Sensors. They are:

- Interior aircraft camera

- Exit perspective camera

- Jumper perspective camera

- Canopy perspective camera

- Overall jump perspective camera

- Nett Warrior device

- SLAAD, or pressure altitude via barometric sensor, solder acceleration via 3-axis accelerometer and soldier rotation via 3-axis gyroscope

“We’re definitely still tweaking,” Corner said of the line-up.

Right now, he added, they’re looking at a 360-degree camera to attached to a soldier’s helmet, which can record what the jumper sees and what’s going on around them, rather than having to clip multiple cameras with different perspectives onto each person.

Fielding PSS will also require full operational capability of Nett Warrior, a handheld device the Army is working on that can track soldiers, send them messages and mark up maps from the battlefield.

It could also support an app that takes camera and sensor feeds from a parachute jump and spits out analysis. Natick is also counting on the Reserve Automatic Activation Device, another in-progress program that would automatically deploy a parachute at a certain altitude, in case a soldier wasn’t able to manually open the canopy.

“We’re still investigating all of those avenues because the futures of Nett Warrior and the Reserve Automatic Activation Device are not set in stone yet,” Corner said.

Next up

The team plans to have nailed down each piece of instrumentation by the end of fiscal year 2019, along with a prototype of the interface to analyze them. Along the way, they’ve been meeting with the Army Airborne Board ― a group of senior leaders in the paratrooper community ― to demonstrate their progress.

“We have plans to bring in airborne leadership, who do investigations, to refine the interface and get it to what they want to use, and also what they would be able to use,” Corner said.

RELATED

The interface will be the most pricey part, he said, costing several hundred thousand dollars to create desktop and handheld app versions loaded with code to analyze and organize data.

The Army is looking at $1,000 to $1,500 per soldier for the cameras and sensors, though many units already have ground and aircraft cameras.

“We’re really trying to tie in things that they’re already getting to make the cost of things more palatable,” Corner said.

And for now, the PSS is focused on the training environment, so the sets would be in units at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, Alaska, and Fort Benning, Georgia.

“The ruggedness of the devices doesn’t need to be combat-level right now,” Corner said. “That could change.”

Though the Army could look into reinforced cameras or sensors that could survive hard landings, smacking into a tree or other accidents that require investigation.

“They’re only a couple hundred dollars. If they smack it on a tree or the ground, they can pop it off and replace it,” Corner said. “A ruggedized [version] could be thousands. It may survive, but it’s also a larger upfront cost.”

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.