The Army is putting together a plan to evaluate tens of thousands of homes with potentially toxic levels of lead after a Reuters report found that more than 1,000 children of soldiers had suffered from elevated levels of lead in their blood while living in on-post housing.

The program would start with homes where small children live, according to Reuters, as they are most at risk for stunted brain development and lifelong health issues.

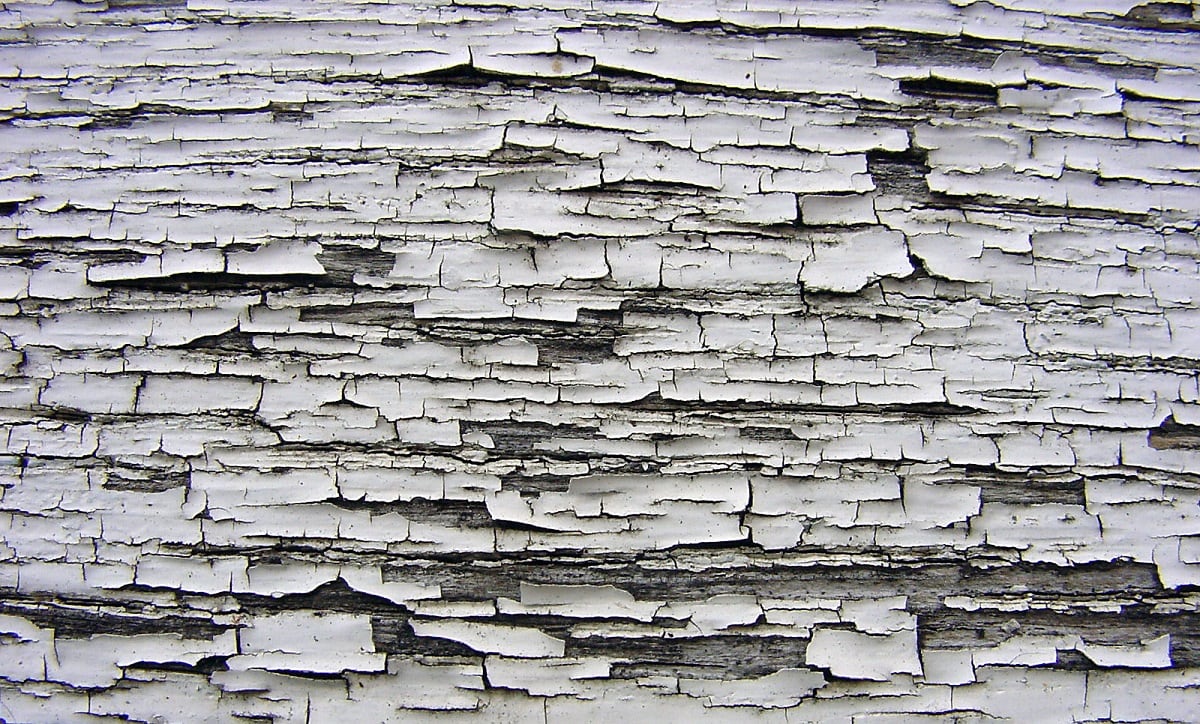

“Our immediate action plans now are to get the word out to everybody ― if you have chipping or peeling paint in your home, immediately notify the garrison. We will get somebody out there that day, as soon as possible, and we will address the issue,” Army Secretary Mark Esper told reporters on Wednesday.

A crisis action team is working on a long-term plan, he added, to inspect and repair all homes affected.

“Part of the way we make a more lethal force is by ensuring the troops aren’t worried about their families back at home,” Defense Secretary James Mattis told reporters on Tuesday. “So this is ― this is a moral obligation we have to the families to provide safe lodging, obviously, for them. And it’s something we take very, very seriously.”

Reuters obtained documentation showing high levels of lead at Forts Benning, Polk, Riley, Hood, Bliss and Knox as well as at West Point, homes of major Army divisions and training centers.

“We are aware some families have expressed concerns about potential risks in government housing,” Army spokeswoman Col. Kathleen Turner told Army Times in a statement. “Out of an abundance of caution, we are going above and beyond current requirements to ensure the safety of our soldiers and their families who work and live on all of our installations.”

While Fort Knox announced a plan to fix the peeling and crumbling lead paint in pre-1978 homes, which can also end up in water and soil, Fort Benning issued messages to family urging them not to participate in any outside investigations, according to Reuters.

“We are currently evaluating all options to address these concerns,” Turner said. "However, at this time no decisions have been made.”

RELATED

It would cost up to $386 million, according to Reuters, to inspect all of the potentially affected homes. Town halls would be held on post to address concerns, according to a draft of the plan. Residents of contaminated homes would be able to temporarily ― or possibly permanently ― relocate if renovations are necessary.

The plan did not clarify how long it would take to inspect or repair the homes, or whether the private contractors who manage much of the Army’s housing would be held responsible.

“We’ve had other environmental impacts on some of our bases. You’ve seen us work to correct those,” Mattis said. "And I have absolute faith the Army’s moving on this quickly. I spoke to the secretary of the Army this morning about this very issue. So they’re ― they’re moving on it.

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.