DENVER — A highly automated, multibillion-dollar plant in Colorado that destroys U.S. chemical weapons is over budget, behind schedule and bedeviled by troubles that could worsen the danger to workers.

But when the Army said this month it wants to spend millions extra installing more traditional technology to help the beleaguered plant and reduce worker risk, public reaction was more resignation than anger.

“Yes, the process has been too slow and too expensive, but this is the price paid to protect the workers and neighbors of this site,” said Marco Kaltofen, a nuclear and civil engineering researcher at Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Massachusetts who has worked on chemical weapons destruction and testing methods.

Defense contractor Bechtel Inc. spent 12 years designing, building and testing the plant at the Pueblo Chemical Depot to disassemble and neutralize 780,000 decades-old shells filled with liquid mustard agent stored at the site.

Mustard agent — first used in World War I — can maim or kill, blistering skin, scarring eyes and inflaming airways.

The heavily guarded depot spreads across 36 square miles (93 square kilometers) of rolling, brushy terrain about 15 miles (24 kilometers) from the city of Pueblo. The plant destroying the weapons is a collection of nondescript industrial buildings and tanks connected by a web of pipelines.

The plant is expected to cost $4.1 billion, including design, construction, operation and disassembly when the work is done, according to the Defense Department inspector general’s office, an internal watchdog. Other costs are expected to push the total price for the operation to $4.5 billion, Army officials said.

The U.S. is obligated to destroy all its chemical weapons under international treaty. The Army has already eradicated much of its stockpile by incineration, which is cheaper per weapon than neutralization.

But faced with state and local concerns about air pollution, the military agreed to destroy the Colorado weapons with water to neutralize the mustard agent and microbes to digest and convert the remaining chemicals. The outcome is a dry “salt cake” that can be disposed of at a hazardous waste dump.

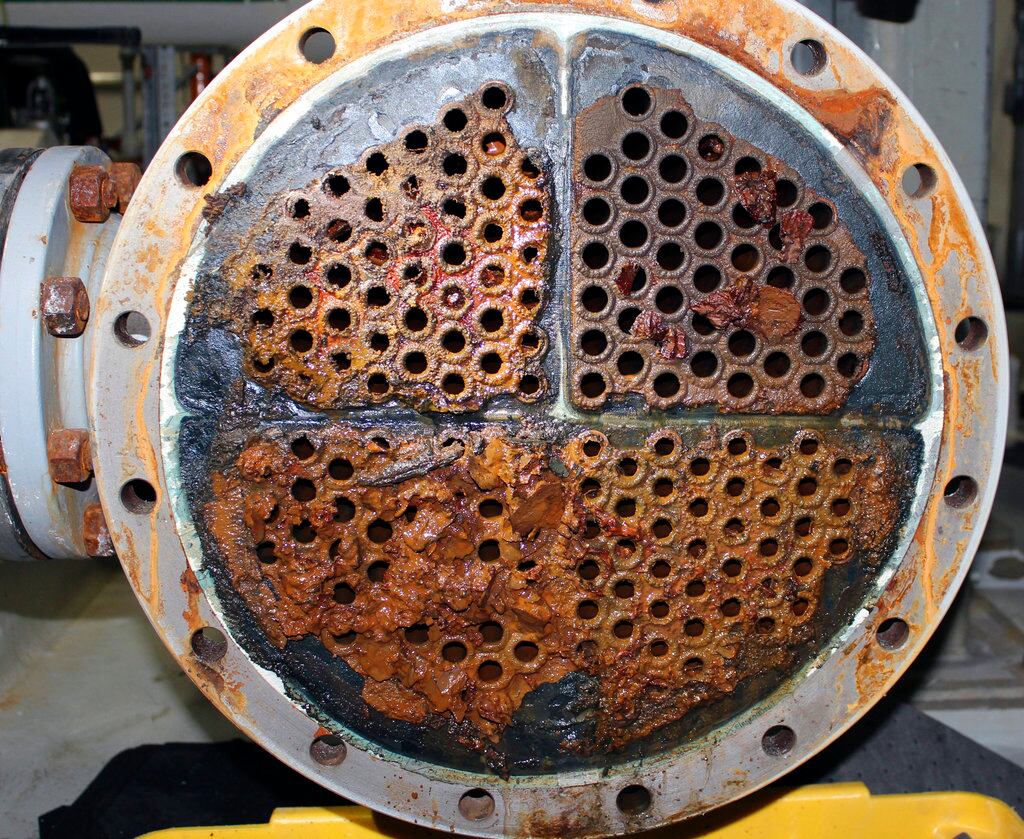

The plant started operating in September 2016 and has destroyed 43,000 shells. But it has endured two long shutdowns because of problems: a leak in a storage tank, a tear in a spill-containment liner at another tank, rust inside shells and vibration in pipes.

Most operations have been halted since September, after operators discovered more rust and other solids in the mustard agent than plant designers anticipated.

The rust clogs pipes and strainers, and officials worry it will make it difficult for the plant’s robotic equipment to open the shells cleanly. Workers have to don protective suits and enter toxic areas to fix the equipment, increasing their risk of exposure.

“The primary issue is worker safety,” said Greg Mohrman, the project site manager.

The Army announced this month it wants to install two closed detonation chambers, costing about $30 million each, to destroy 97,000 shells considered most likely to have excess rust and solids.

The shells wouldn’t have to be opened before they’re placed in the chambers. The chambers would heat the shells to about 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit (540 Celsius) to detonate or burn them and the mustard agent. Gases would be captured, burned and filtered.

That has revived Colorado’s concerns about air pollution, but residents and officials have mostly refrained from criticizing the plan while they wait for details. Some have questioned why the plant designers didn’t anticipate how serious the rust problem would be.

“My perspective is that they probably do have a legitimate problem, but it’s one they should have anticipated,” said Ross Vincent, a member of a citizens advisory group for the Pueblo plant. “They’ve known for many years that some of the rounds are going to contain that stuff.”

The Army still must conduct an environmental study, get state and county permits and figure out how to pay for the chambers.

Army officials have asked the Colorado health department general questions about permits but have not applied for them, department spokeswoman Jeannine Natterman said. Pueblo County officials didn’t return calls.

The Blue Grass Army Depot in Kentucky is preparing to destroy a smaller but more deadly chemical weapons stockpile — it contains nerve agents as well as mustard agent. Blue Grass will use a different type of neutralization on some weapons and will destroy others in a closed detonation chamber.

The Blue Grass plant — also over budget and behind schedule — is undergoing testing but isn’t yet operating.

The inspector general reported last month the Colorado plant will likely wind up $513 million over budget and the Kentucky plant $357 million, but the predictions generated little public attention.

This story has been corrected to show Marco Kaltofen is a researcher in nuclear and civil engineering, not nuclear and chemical engineering.