DENVER — The U.S. Army wants to change the way it destroys part of its huge stockpile of obsolete chemical weapons in Colorado, but some people worry that could increase the chances of contamination escaping into the air.

The Army’s Pueblo Chemical Depot is eradicating 780,000 shells filled with thick liquid mustard agent — many of them dating to the Cold War — under an international treaty banning chemical weapons.

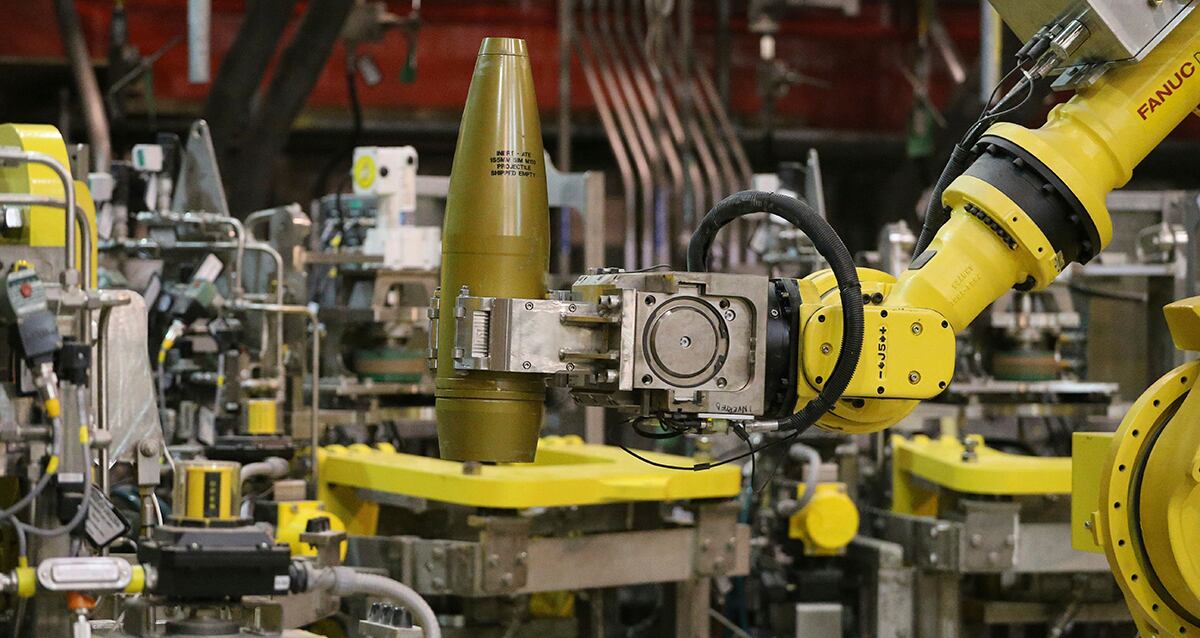

The Army built a highly automated, $4.5 billion plant to do the work, but officials said this week they want to buy two closed detonation chambers for about $30 million each to destroy 97,000 problematic mortar shells. The plant has also experienced a series of setbacks and is currently shut down.

It still has to complete an environmental impact assessment and get state and local permits before proceeding.

The mustard agent in the shells is believed to be contaminated with more rust than originally expected, making it difficult for the plant’s robotic equipment to open them, said Greg Mohrman, the project site manager.

If the shells don’t open cleanly, workers would have to don protective suits and intervene, Mohrman said. That increases the risk they would be exposed to mustard agent, which can maim or kill by blistering skin, scarring eyes and inflaming airways.

“The primary issue is worker safety,” he said.

RELATED

Mohrman said the shells would not have to be opened if they are destroyed in the detonation chambers. The chambers would heat the shells to about 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit (540 Celsius) to detonate or burn them and the mustard. Gases would be captured, burned and filtered.

Mohrman said the technology is safe and has been used to destroy chemical weapons in Alabama and Kentucky as well as seven other nations.

At least two members of the Pueblo depot’s Citizens Advisory Commission, established by Congress as a liaison between the public and the plant operators, have reservations.

“I am very, very concerned on the control of the air emissions — what comes out, how it is controlled,” said Irene Kornelly, the longtime chairwoman of the commission. “And those are issues we really want to delve into.”

Commission member Ross Vincent said he hopes the environmental impact assessment will provide more details about the emissions.

“No matter how hard they try to remove them, some of them get away. There’s no way to avoid that,” he said.

Kornelly and Vincent agreed worker safety is paramount.

“We can’t continually have workers in (protective) suits going in and cleaning up the mess,” Kornelly said.

If and when the Army decides to buy the chambers, it could take two years to have them delivered, installed and put to work, Mohrman said.

He believes money for the chambers is available through an Army office that oversees the destruction of weapons, but isn’t sure if Congress would have to approve the purchase.

Mohrman said the rust comes from water contamination that was in the mustard when the shells were assembled. The water reacts with the mustard agent to create an acid that corrodes the inside of the shells.

The type of steel and the design of the 97,000 mortar shells are different than the other shells at the Pueblo depot, making them more susceptible to rust, Mohrman said.

Vincent questioned why the Army didn’t better prepare for the rust problem when defense contractor Bechtel Corp. designed and built the plant.

Mohrman said the Army did anticipate some rust, but it was worse than expected.

The plant uses a combination of water and bacteria to neutralize the mustard agent after it is drained from the shells. Operations began in September 2016 after 12 years of construction.

The rust is the latest in a series of setbacks. Full plant operations have been suspended since September 2017 because of a leaking shell and problems with a cooling system and a system that circulates liquid as part of the neutralization process.

Last summer, the Army had to truck about 250,000 gallons (946,000 liters) of wastewater to an incinerator in Texas because the Pueblo plant could not process all of it at the time.

Mohrman said he hopes the plant will be back in full operation in May.