FORT CAMPBELL, Kentucky — Over the distant sound of machine gun fire on a neighboring range, an Army staff sergeant shows a huddle of soldiers the proper way to grip the Army’s new pistol.

The soldiers then line up to fire, two rounds at a time, at 5, 10, 15 and 25 yards, to familiarize themselves with the newest addition to the soldier’s arsenal — and only the third handgun the Army has widely fielded in a century.

Some of these soldiers previously qualified on the M9 pistol, the Army’s standard sidearm since the mid-1980s.

For a handful, this is their first pistol qualification. One specialist had never fired a handgun in his life, but qualified anyway as a sharpshooter after a few minutes of hands-on instruction.

“It was a lot easier than I thought it was going to be,” said Spc. Judd Perez, a soldier with B Company, 1st Battalion, 506th Infantry Regiment, 1st Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division.

Other than a bayonet or hand-to-hand fighting skills, a pistol is the shortest of short-range weaponry a soldier might use in combat. And except for military police and special operations forces, the sidearm was a low priority for decades, taking the back seat to bigger systems such as vehicles, tanks and artillery.

But after 16 years of war, much of that including close-quarters fighting, the Army and the other services are putting more weight behind improving all things infantry.

And the handgun is one of the first, and most tangible, of those changes.

No longer is it just a weapon of last resort or an item suited only for certain personnel who would rarely come in close contact with enemy fighters.

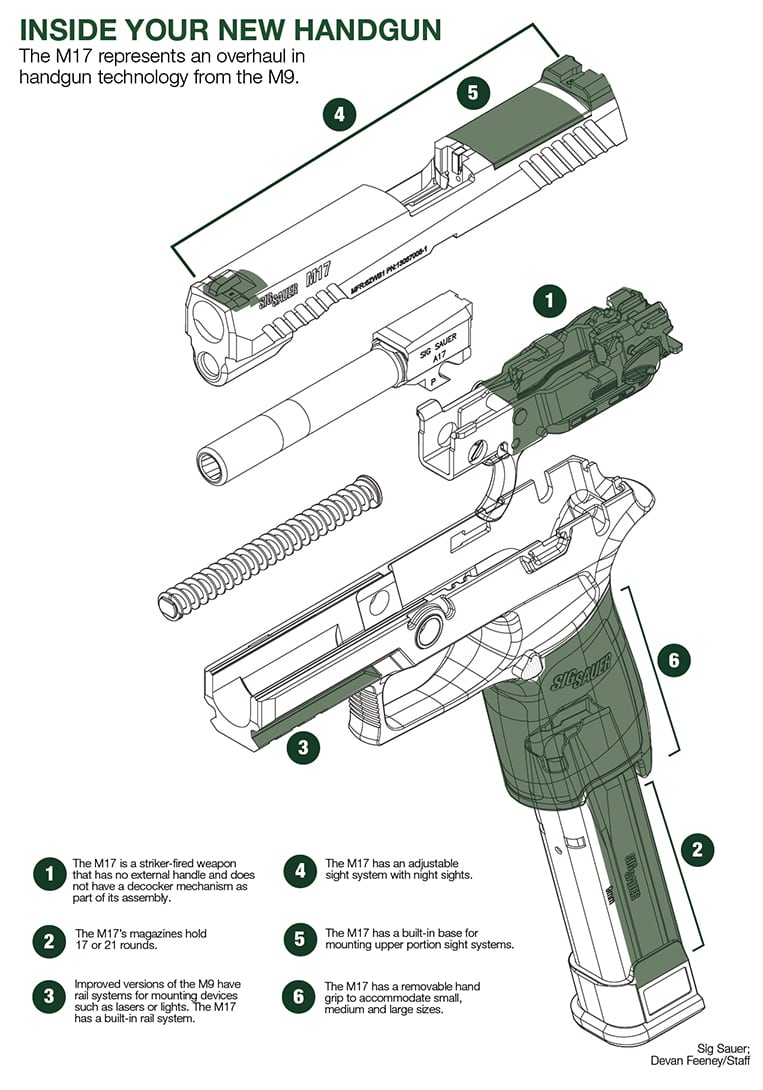

From the pistol design, to the holster that carries it, to the bullet it fires, the M17 is an updated sidearm in every sense, showcasing most of the advancements in handgun technology made since the M9 was adopted more than 30 years ago.

“This is an offensive capability,” said Daryl Easlick, deputy at the Army’s Maneuver Center of Excellence Lethality Branch. “It’s not a defensive weapon.”

Though the handgun developments predate official reviews now being conducted to better train and equip the lowest-level tactical warfighter, it is a signal of a larger trend suddenly sweeping the services.

And at least one vocal supporter says it’s about time.

“This is just part and parcel of a larger thing,” said retired Maj. Gen. Robert Scales. “It’s just like all of the sudden we’re seeing a renewed interest, driven by how we have neglected the close combat function.”

Scales, author of “Scales on War: The Future of America’s Military at Risk,” has spent years advocating for just such a change to the lethality of the individual soldier, Marine or special operator, amid fears that the individual warfighter is facing an overmatch against adversaries in close combat.

‘Weapons systems’

Defense Secretary Jim Mattis and others are shifting thinking at the Pentagon to focus on increased lethality for infantry and ground combat elements of the military.

“The Department of Defense is conducting a study to enhance lethality and reduce loss of life for our dismounted warfighters in close combat,” said Christopher Sherwood, a Pentagon spokesman. “Equipping solutions are being considered to improve firepower, soldier load, protection, and situational awareness.”

Sherwood added that officials are assessing training and talent management policies to “enhance the cognitive and physical development of the infantryman.”

He declined further comment, but other sources confirmed that the close combat study being conducted throughout the services by the Pentagon’s Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation, or CAPE, is reviewing the individual warfighter and small unit as a “weapons system” much like an aircraft carrier or fighter jet.

Additionally, the department is conducting a comprehensive assessment of the services’ training and talent management policies to enhance the cognitive and physical development of infantrymen.

At the Army’s Maneuver Center of Excellence at Fort Benning, Georgia, staff are already contributing to the first phase of a detailed study into close combat.

Maj. Gen. Eric Wesley, commander of the Maneuver Center, said some of the initial items look at accelerating materiel solutions such as the Next Generation Squad weapons program, smaller drones, lighter body armor and enhanced night vision.

But the deeper, longer-lasting and more human-focused work is likely to take place in phase two, which will focus on training and human performance.

“It’s starting with a wide aperture, considering many ideas, including changes to how the Army recruits, trains, mans and develops the close combat force, to have experts operating at peak performance while operating on a multi-domain battlefield,” Wesley said.

Able to fight

The soldiers of the 101st Airborne Division who recently qualified on the new M17 handgun are just a small sample of the soldiers, Marines and special operations forces likely to benefit from this renewed focus.

Currently, Marines and soldiers are employing greater firepower such as the Carl Gustaf 84mm recoilless rifle at lower levels within infantry units, experimenting with suppressed fire to gain tactical advantages and, for the first time in half a century, putting real investment and resources into a new caliber of individual rifle.

A slight change in issuing the new pistol — issuing the new handgun down to the team leader level — signals a larger recognition of 21st Century battlefield realities: soldiers are having to do more in more dangerous, up-close situations than ever before.

“If I’m clearing a cave, tunnel or crawlspace, dragging a litter or climbing a ladder, I still need to be able to fight,” Easlick said.

It also offers a way for soldiers to tailor their equipment for their missions.

Much like the Army’s new body armor system gives soldiers different layers of protection — from an undershirt to full combat protection — the handgun allows soldiers to remain armed in situations such as meetings with tribal leaders in Afghanistan without being seen as a threat.

“One issue is a green-on-blue threat,” Easlick said, referring to cases of insider attacks. “If I was to go into a key leader engagement, culturally it’s not okay to stand there with my long gun still slung.”

Easlick explained that the Army’s decision to dual-arm team leaders and above was directly related to feedback from the battlefield and what soldiers said they need.

“When we’re a nation at war, you get a different feedback than when you’re a nation not at war,” Easlick said.

The issuance goes further: commanders can decide to put the pistol on soldiers at even lower levels, should the need arise, Easlick said.

As 2nd Lt. Connor Maloney pointed out at the Fort Campbell range, his company now has 46 M17 pistols at their disposal as opposed to previously carrying only nine M9s.

“It just improves our lethality as a force to have more soldiers armed with this weapon,” Maloney said.

Sgt. Stephen Pynn, also with 1st Battalion, 506th Infantry, said there was an immediate difference in how the new pistol fired compared to the M9.

“One of the big differences is I know the M9 we previously had, it was double action, so a lot of guys were hesitant with that first trigger squeeze,” Pynn said. “But with the new one it’s real simple. … It’s real easy.”

The integrated rail system adds another capability, Pynn said.

“Mounting a laser on it, now we can incorporate these into more night ops,” Pynn said. “We’ve never been able to do that before.”

These changes effectively broaden a short-range weapon that has, for decades, been the sole weapon of a higher-ranking commander or only put in the hands of troops in specific roles, for example military police, criminal investigators or in special operations units such as Rangers or Special Forces.

How we got here

The Army’s new handgun is the result of an Air Force program that began in 2008 and was moved to the Army in 2010, Easlick said.

It was not the first attempt to replace the Beretta-made M9. Short-lived programs over the past decade included the Future Handgun System, the Joint Combat Pistol and the Combat Pistol Program, none of which resulted in an adopted replacement.

Sig Sauer, the company that makes the M17, competed against Beretta for the original 1985 contract. Even though Beretta won out, Sig’s offering, the P226, was later adopted by special operations forces and Air Force pilots.

Last year, in the race for the M17, Sig beat Glock, Beretta and FN America for the 10-year, $580 million contract to produce more than 200,000 of the Army’s new pistols.

In searching for a new handgun, military small arms experts noted several deficiencies in the M9 that officials determined could be fixed by a replacement rather than modifications.

Some of those shortcomings included a slide-mounted safety, the lack of a built-in rail for mounting devices, the inability to change the ergonomics of the weapon for different hand sizes or grips, and a fixed blade that didn’t offer an effective night sighting.

The project began as non-caliber specific, opening the design to calibers other than the 9mm.

Ultimately, the Army stayed with the 9mm, but for the first time has authorized hollow point bullets — which have a more lethal effect than standard ball ammunition — for use in the soldier’s standard issue sidearm.

One reason officials stuck with 9mm, Easlick said, was accuracy. An average shooter can handle the lesser recoil of the 9mm, staying on target in rapid fire modes much better than with the .40 caliber or .45 caliber rounds.

RELATED

Not just a gun

Beyond the bullet, officials viewed the handgun as a system rather than a singular weapon.

The initial commercially available holster being used for the weapon is the Safariland 7TS holster.

It is a rigid plastic holster with two securing methods — a thumb break locking lever and a rotating strap.

The two methods give soldiers multiple options to keep the weapon contained, and the rotating strap gives soldiers additional security while performing tasks such as fast roping or rappelling.

The holster can be fixed on the belt or strapped to a soldier’s thigh to accommodate other gear and body armor on the torso.

This is also a change from the original M9 holster, which was often belt-mounted with a large flap-like cover to secure the weapon, making it difficult to quickly draw the sidearm when needed.

Two more holster variants are expected. One will be for the M18, the smaller-framed M17 designed for carry by military police, investigators and soldiers on special duties. The other holster will be developed to accommodate a suppressor and laser aiming or light devices.

Though the Modular Handgun System is designed to have interchangeable parts as needs arise, such as a new holster design or various add-ons for the pistol, the gun itself is expected to be in the Army inventory for as long as the next 30 years.

“We don’t get new guns, we get guns refurbished,” Easlick said, adding that 80 percent to 85 percent of the M9s in the Army’s inventory have serial numbers that date back to before 1990.

But no matter how good the new gun is, training is where its effectiveness will be revealed.

Whether it’s with the handgun, a new rifle or other small arms, Scales said that while better equipment can help, nothing replaces ongoing training.

“What’s often missed in all of this is the value of just plain shooting,” Scales said. “It’s not that [special operations] has a better pistol, it’s that shooting becomes an extension of their arm. It’s second nature for them. There’s no substitute for shooting 2,000 rounds a month.”

To that end, weapons experts with the 101st Airborne Division are developing a dual weapons training course that will specifically focus on shooting transitions between the M4 carbine and the M17, said Lt. Col. Martin O’Donnell, a spokesman for the division.

“We are absolutely looking to others who have perfected the trade, but what we need is something uniquely tailored to the conventional forces and the team leader and above role,” O’Donnell said.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.