FORT BENNING, Georgia — The young Army infantry recruits lined up in full combat gear, guns at the ready. At the signal, a soldier in front kicked in the door and they burst into the room, swiveling to check around the walls for threats.

“You’re dead!” one would-be enemy yelled out from a dark corner, the voice slightly higher than the others echoing through the building.

It was 18-year-old Kirsten, training to become one of the Army’s first women serving as infantry soldiers.

“I want to be one of the females to prove to everybody else that just because you’re a female, doesn’t mean you can’t do the same things as a male,” she said, describing her brother — an infantry soldier — as motivation. “I also wanted to one-up him.”

Kirsten is among more than 80 women who have gone to recruit training at Fort Benning, Georgia, since a ban on them serving in combat jobs was lifted. Twenty-two have graduated. More than 30 were still in training late last month, working toward graduation. The recruits’ last names are being withheld by The Associated Press because some women have faced bullying on social media.

Somewhat smaller in stature than some of her male comrades, Kirsten gave up a Division I soccer scholarship to become an infantry soldier. In body armor, helmet and rucksack, she looks like just any other grunt.

A bunkmate, Gabriella, says the women push each other.

“Today during our ruck march we were, like, directly across from each other and I would constantly look over at her,” Gabriella said of Kirsten. “We kinda just kept looking at each other and we’re, like, all right, we’re both doing it, we’re passing these guys and stuff. We definitely have goals to be better than the guys.”

The Army’s introduction of women into the infantry has moved steadily but cautiously this year. As home to the previously all-male infantry and armor schools, Fort Benning had to make $35 million in renovations, including female dorm rooms, security cameras, and monitoring stations.

Laundry was an early challenge.

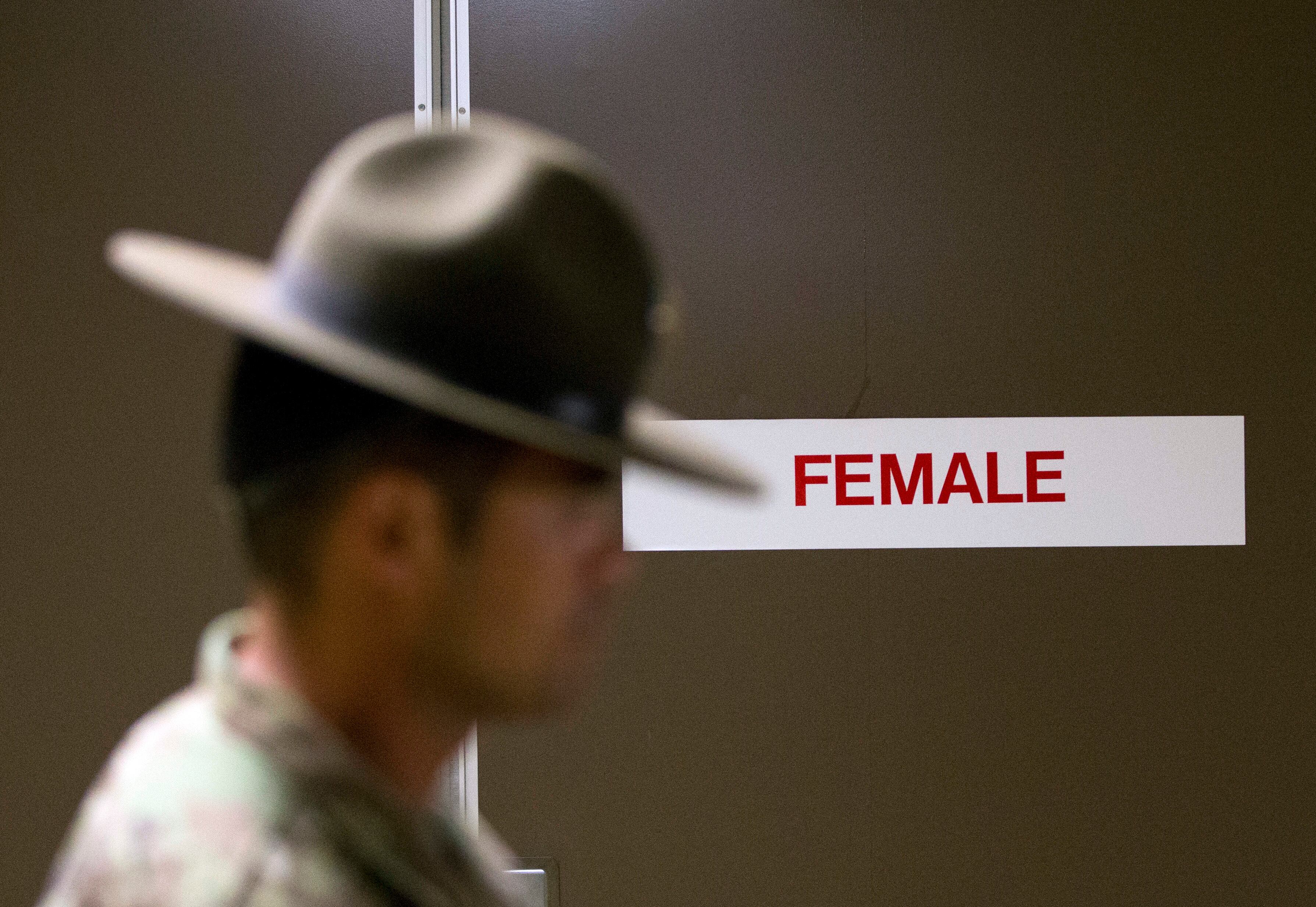

For years, the men washed clothes any time at night. Now, there are alarms and schedules. A “female” sign goes on the door when needed.

The women also balked at the early plan to put their living quarters on a separate floor from their squadmates. So base leaders now use one of four main sleeping bays to house the women. Cameras keep constant watch on the bay door and the stairs, and there’s always a woman at the monitoring station.

“There’s nothing they dislike more than to be separated,” said Col. Kelly Kendrick, the brigade commander. He said the women just want to “fit in and do the same as everybody else.”

This is the third class of recruits at Benning to include women. When they’re not sleeping or washing clothes, they’re completely integrated into their units.

As sun peeked over the horizon on an October morning, dozens of infantry recruits spread across the Fort Benning field going through their morning PT drills. In the dark mist, it was difficult to tell one from another as they powered through situps and pushups.

On that day, only two of five battalions training were integrated. There still aren’t enough women to spread across all the units.

The shortcoming has created challenges. In the last class, only four women graduated, so filling rotations for guard duty all night was a problem. There weren’t enough women to cover every hour, so others had to fill in.

And as women drop out, those remaining are moved to new companies to maintain balance within units, said Lt. Col Sam Edwards, commander of 1st Battalion, 19th Infantry regiment. More than 36 percent of Benning’s women have left — about twice the rate of men. Injuries have sidelined other women who plan to restart the training.

Army leaders are closely watching the integration to track injury and performance trends and ensure there are no problems.

“It was a boys club for a long time,” Kendrick said. “You have to be professional.”

Recruits seem unfazed.

“They don’t know any different. They don’t notice they’re integrated,” Edwards said. Most just left high school, where boys and girls mingled all the time. “That’s the way it’s always been.”

Commanders are adjusting to new concentrations of injuries among the women. While male recruits often get ankle sprains and dislocated shoulders, women are prone to stress fractures in their hips. In the latest class, six of the seven injured women in Charlie Company had hip stress fractures.

Half of the women, Kendrick said, weigh less than 120 pounds (54 kilograms), but all the recruits carry the same 68 pounds (31 kilograms) of gear.

As a result, female recruits need different advice, tailored injury prevention training, and iron and calcium supplements.

Across the base, Charlie Company is in a mock village, training for combat in urban environments, just hours after finishing a 12-mile march (19 kilometers). They kick through doors, scout for enemies and listen as drill sergeants bark out criticism and corrections.

Those sergeants say all the recruits ask the same questions.

“They want to know how to run faster,” said Staff Sgt. Raven Barbieri. “They ask, ‘How do I pack my ruck better?’”

She said some women ask how to put their hair up properly. But more often, they seek tips for getting through long marches.

Sitting on the bleachers for a quick lunch, Kirsten said her brother showed her how to pack the ruck so it doesn’t overly stress her hips or shoulders. He told her: “Always bring extra socks and always bring baby wipes because you’re not going to be able to shower.”

Corbin, 19, shrugged off questions about women in his company.

“They’re pulling the same weight that we’re pulling,” he said, sitting alongside Kirsten and Gabriella. “As long as they’re pulling the weight that we’re doing and we can have faith that out in the field they can have our backs while we have theirs, then let them be.”

In a way, said Corbin, whose last name also was being withheld, the women ensure there are no laggards among the men, because they’d be ridiculed for finishing behind others. “It just makes everyone have a mindset that you can’t be the last one,” he said. “You gotta keep striving to be better than that person in front of you. No one wants to be the last person.”

The recruits are preparing for their final training exercise and the road march to Honor Hill, where they’ll receive their infantry badges in a solemn soldiers-only ceremony. For the women, it will be an especially powerful moment.

“Once I do reach Honor Hill, I think that it’s like a huge sigh of relief, and like all this weight is taken off my shoulders and knowing that I did it and made it,” Kirsten said. “To make it through infantry training, it will feel really, really good.”