Top to bottom, the Army is changing the way it educates soldiers.

From professional military education to the transition back to civilian life, the Army is trying to grow better leaders and give soldiers tools to translate their knowledge into civilian education, officials said during a presentation Oct. 10 at the Association of the U.S. Army’s annual meeting in Washington, D.C.

“The noncommissioned officer education system began in 1973. But it was time to reexamine the way we were developing leaders,” said Command Sgt. Maj. David Davenport, the senior enlisted soldier at Training and Doctrine Command. “What we came up with, it was more than just PME. We wanted this well-rounded noncommissioned officer, with a broad set of skills and experiences.”

Those changes include the end of Structured Self-Development distance learning, a revamped Basic Leader Course, course credit for the Sergeants Major Academy, opportunities for soldiers to earn non-academic credentials, and a couple of documents that can help soldiers translate their education after they transition back to civilian life.

Goodbye, SSD. Hello, DLC.

Soldiers might be doing their at-home professional military training modules on a computer now, but the Structured Self-Development courses that eat up so much of an NCO’s time are actually based on a system developed back in 1973.

“It’s been over 43 years since we’ve touched anything in our NCO education system,” said Command Sgt. Maj. Jimmy Sellers, commandant of the U.S. Army Sergeants Major Academy.

“Our problem was that we were driving this vehicle of NCO professional development system for about 34 years, with no change,” he added. “We kind of kicked the tires, changed the tires, did some updates to the system. All we were doing were oil changes.”

A study of PME, with soldier and leader input, found a stagnant, disorganized system.

“We confirmed [that] we are who we thought we were,” Sellers said. “We lacked a lot of communication skills. Our PME was not synchronized. There were really no true outcomes. Everyone was kind of rowing their own boat depending on what PME you went to.”

RELATED

Beginning in June 2018, that’s all over. The Army is scrapping SSD for a new system called the Distributed Leader Course.

It’s still many hours sitting at a computer, officials said, but the new Distributed Leader Course experience is completely different.

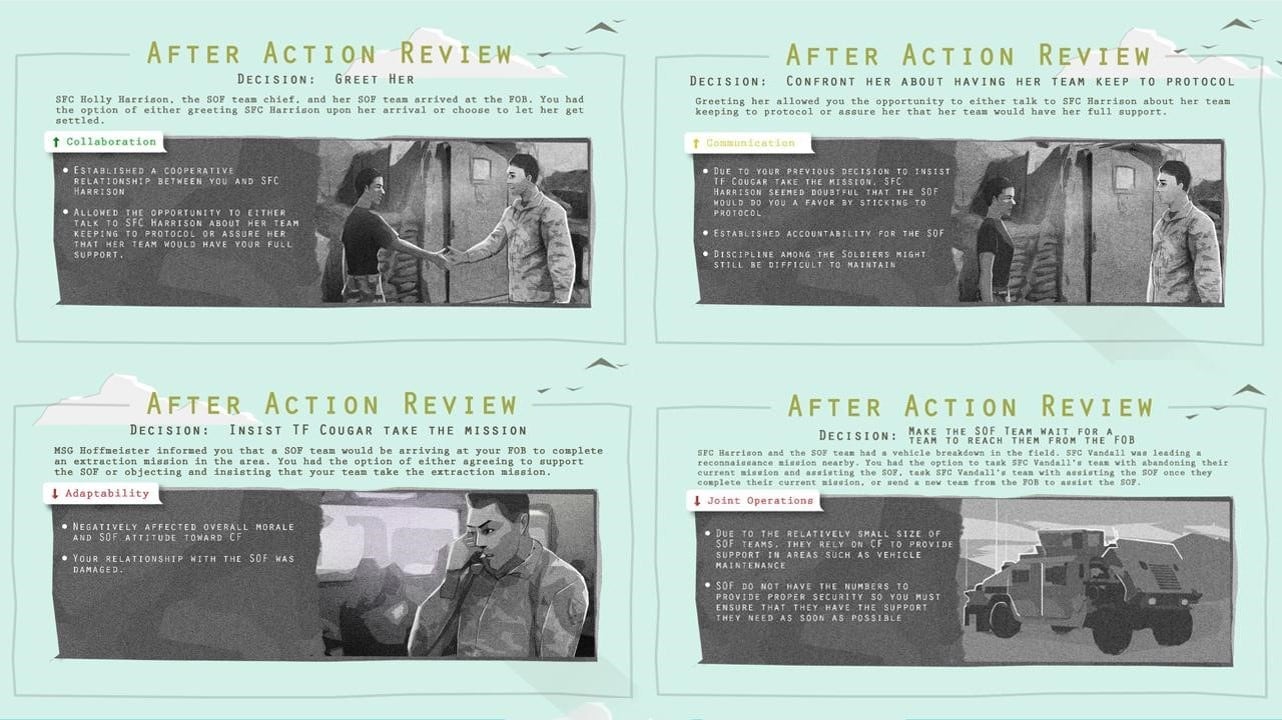

“If you’ve ever seen or played the game ‘Call of Duty,’ it comes up just like ‘Call of Duty,’ ” Sellers said. “It describes everything they have to do inside the mission.”

Rather than clicking through a series of pictures, the course takes a soldier on a sort of “choose your own adventure” track.

“Every decision that a soldier makes, in terms of DLC, is graded and evaluated,” Sellers said. “If they make a decision based off the mission statement to do one thing, it can cost them some points in terms of their overall grade.”

At the same time, good decisions can raise scores.

“They’re just not sitting behind a screen clicking. They’re actually learning,” Davenport told Army Times. “Along the way, if they don’t meet a gate, it comes back at the end and tells them what they need to go back and work on. Instead of, ‘You just failed, redo it again.’ ”

And if you do fail, Sellers said, the system locks you out for 30 days and sends a note to your NCO in charge.

The content will also be different. From its study of PME, the Army settled on six leader core competencies that all NCOs, regardless of military occupational specialty, must master.

“The artist formerly known as ‘common core,’ ” Sellers said.

Those six must-haves are readiness, leadership, training management, Army and joint operations, program management and communication.

“[The Advanced Leader Course] and [the Senior Leader Course] really had no leadership,” Davenport said. “There is very heavy technical and tactical training in there.”

Soldiers will now be tested on those at every level of DLC and schoolhouse PME. DLC courses will also feed directly to the Basic Leader Course or Advanced Leader Course, for example, to prevent soldiers from studying up for the computer course and then forgetting everything they learned.

“When you get to ALC, DLC II will be tested again,” Sellers said. “There’s no longer a brain dump. It’s progressive and sequential.”

And the score you get on DLC will be your baseline for the following leader course, Sellers said, so soldiers with low distance learning scores will have to make up ground in the schoolhouse.

“In the end, what I hope soldiers don’t think is that it’s just a name change,” Davenport said. “It looks nothing like SSD.”

All-new Basic Leader Course

In order to thread these new leader core competencies up the chain of PME, TRADOC decided it was time to overhaul the Basic Leader Course, which is the Army’s first NCO development school.

The new BLC, according to TRADOC, will still take the traditional 22 days or 169 hours to complete, but the rest looks very different.

Rather than three modules, the course is divided into the new core competencies. Specialists will spend between seven (program management) and 42 (leadership) hours on each.

There will be fewer lessons — 22 rather than the current 30 — but also no multiple-choice exams.

“When you take a look at BLC and the redesign, the main point that soldiers should take away from it is — we’re teaching soldiers, soon-to-be noncommissioned officers a lot about how to train,” Sellers said. “Instead of training them, we’re teaching them how to train.”

Rather than teaching specialists how to do things and trusting they’ll take them back to their units and figure out a way to break them down for junior soldiers, BLC will teach them effective ways to pass on training.

“They’re going to be able to go back to their organizations and teach their soldiers about land [navigation] and map reading, by giving them certain tasks,” Sellers said. “[BLC will be] evaluating them on how well they execute the task and train the task to their fellow peers, before they go back to their organizations.”

Evaluation, Davenport said, will start with an assignment of a specific warrior task.

“He’s going to have to, or she’s going to have to, look it up, develop a lesson plan, give the class, record the training,” he said.

This will not only start leadership and management training from a lower level, Davenport said, but it will standardize PME according to the goals laid out in doctrine.

“It used to be that when they went back to the brick-and-mortar, and you go back to your unit, they could say, ‘Oh, that’s not the way we do it here,’ ” he said. “Now, it’s to the standard, according to doctrine. That’s the reinforcement time of what they’ve learned in BLC.”

College credit at USASMA

If the Army’s leadership course continuum is like a military version of primary and secondary school, the U.S. Army Sergeants Major Academy is its institution of higher learning.

Now, officials are working on codifying that idea, by getting the 10-month senior NCO school credentialed for undergraduate course hours.

In mid-November, the Fort Bliss, Texas, school will be evaluated by the Higher Learning Commission, Sellers said. The goal is to gain approval for the education provided by USASMA to be worth between 40 and 42 hours of bachelor’s degree course credit.

“That means that if you’re a sergeant major that comes in with no degree, this is an opportunity, based on our new curriculum, to walk out the door with a bachelor’s degree,” Sellers said.

Specifically, sergeants major who have started working on a degree can include the USASMA course work, or those who haven’t done any college can use USASMA as a starting point.

The school can be divided into four academic departments, Sellers said: Military Operations, Force Management, Command Leadership and Professional Studies.

The curriculum falls under a degree in leadership and workforce development.

Students can also use USASMA courses toward credentials or certifications.

“For example, I’ll use myself as a supply logistician,” Sellers said. “If I got to the Department of Professional Studies and wanted to do something like functional training and support operations, because I know that I’m going into a support operations job, I can do that for a couple of weeks and get certified there.”

If USASMA gets approval to offer college credit, a pilot would begin with class 69, which begins next summer. Class 70 would then be the first fully accredited course, Sellers said.

TA for credentials

One of Sergeant Major of the Army Dan Dailey’s top initiatives this year has been creating a program for the Army to pay for civilian credentialing for troops, whether the certificates pertained specifically to their MOS or not.

That plan is still underway, Dailey said Oct. 10, and it’s doable within the Army secretary’s powers.

But credentialing costs money — some of the most highly technical ones can cost thousands and must be renewed regularly, so Dailey said he is working with Congress to allow soldiers to use education dollars already available to them.

“My goal is to get [tuition assistance] and credentialing assistance equal,” he said.

RELATED

The law that allows the military to pay up to a certain amount of service members’ college tuition and fees prevents that pot of money from being used for credentials.

“I’m working with [the office of the secretary of defense] and Congress to figure out how to fix that,” Dailey said.

A working group with Ray Horoho, the Army deputy undersecretary for manpower and reserve affairs, Dailey added, is putting together a credentialing pilot program, which will be funded.

New DA Form 1059

To help keep track of all of the PME soldiers complete, the Army is working on a new Service School Academic Evaluation report, to be fielded in December 2018.

“First of all, we’re moving away from bullets to an all-narrative,” Davenport said. “NCOs, instructors are going to have to write about their soldiers.”

RELATED

The new DA form 1059 will be filled out at each level of PME, to include class standing, PT score, height and weight, Multi-Source Assessment and Feedback 360 and writing assessment score.

“As you may be aware, if you’re keeping up, one of the tenets in the [Leader Core Competencies] is a communication program,” Davenport said, so the form will include grades on oral presentations and written ability.

Davenport jokingly included a bit of trivia in his explanation: “SMA Dailey was No. 1 of 500 at USASMA. Sgt. Maj. Davenport was 500 of 500.”

Army U transcript

To tie all of this together — PME, credentials, USASMA college credits — the Army wants soldiers to begin putting together a transcript of their professional education, starting at BLC.

The plan has been in the works for years, and Davenport said a pilot program would soon begin testing at Fort Benning’s armor school.

RELATED

The transcript would pull from all 28 of the Army’s personnel databases, he said, to accurately lay out a soldier’s education and experiences in one document.

“So, when that soldier transitions, and they go to an academic university, to the registrar’s office, it’s clear what that soldier did while they served our great country,” he said.

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.