Amid an uproar from active and former Special Forces soldiers over uniform items and his comments on the history of SF training missions, Army Chief of Staff Gen. Mark Milley took to the Army Times comments section Monday night to clarify his remarks.

The controversy began late last week when a photo of a green-ish beret and Instagram posts of uniform patches belonging to the 1st Security Force Assistance Brigade — looking suspiciously like uniform items worn by the Army’s storied Special Forces groups — made the rounds on social media.

RELATED

Tempers flared again Monday, when Milley told Army Times that SFABs would focus on training conventional troops, which the U.S. has done for decades, adding that SF did not train Afghan National Army or Iraqi Security Forces troops.

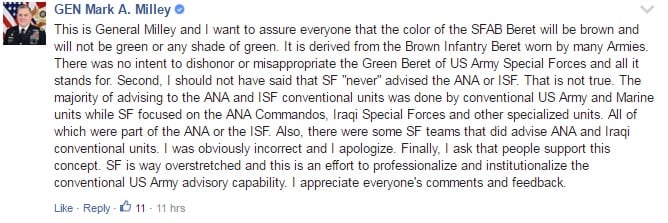

In a mea culpa posted to the original story, Milley explained his original statement.

“I should not have said that SF ‘never’ advised the ANA or ISF. That is not true,” he said. “The majority of advising to the ANA and ISF conventional units was done by conventional US Army and Marine units while SF focused on the ANA Commandos, Iraqi Special Forces and other specialized units. All of which were part of the ANA or the ISF. Also, there were some SF teams that did advise ANA and Iraqi conventional units. I was obviously incorrect and I apologize.”

Milley clarified to Army Times that the beret color, when it is fully fielded, will be brown. The original prototype was inspired by the British Royal Anglian Regiment’s berets, a color historically associated with infantry units.

“I can understand their anger and wrath,” he said. “And all I’m trying to do is help explain.”

RELATED

SF vs. SFAB

Beyond the controversy about uniform items, some in the Special Forces community have questioned the mission of SFABs, as SF has a storied history of training foreign troops.

But they haven’t been the only ones, Milley told Army Times on Monday. Two of the most notable organizations were the Korean Military Advisory Group and Military Assistance Command-Vietnam, and both included conventional troops.

Since the beginning of the Global War on Terror, the majority of conventional Afghan and Iraqi troops have been trained by conventional U.S. forces on an ad hoc basis, he added.

“Special Forces has gone out and done what they’re supposed to do, and only they can do, which is train irregular forces,” Milley said.

Conventional forces are more suited to teach artillery, armor, aviation and other specialties, he said.

“[Special Forces] can’t really train the scope and level of training of an entire national army,” Milley added. “ It fell to the regular Army to do it.”

In recent years, the Army has sent headquarters units to train, advise and assist conventional units, ripping apart brigade combat teams in their deployment cycle, leaving the combat troops at home.

“Right now I’ve got nine brigades that are linked to the Middle East, who have just returned, are there or are ready to go there,” Milley said. “I only have 31 brigades, and nine of them are wrapped up doing this.”

Breaking up those brigades prevents them from training as a whole for combat deployments, which are more and more at the forefront of the military’s priorities as tensions rise in Korea and Europe.

RELATED

“I need to get those units back and get their readiness up to speed,” Milley said.

He also believes that the train-advise-assist mission will continue long into the future and is in need of professionalization.

“There is no intent to replace Special Forces, or to compete with Special Forces,” Milley said. “This is a unique mission gap that needs to be filled.”

That’s not to say that SFABs won’t ever be collocated with SF in the same region, but they won’t necessarily be, Milley added.

For example, conventional and SF units are both deployed to countries like Niger and Cameroon supporting regional stability in separate missions.

RELATED

“The combatant commander should apply any force — Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines — in accordance with their capabilities and limitations,” Milley said.

Battle-tested

On top of concerns over the core missions and heraldry of SFABs, others expressed concern that military training advisers would not be prepared to enter some of the austere, denied environments where SF operates.

Milley reiterated that those missions would continue to fall to special operations units, but that SFAB soldiers would be fully qualified to advise not only in Iraq and Afghanistan, as conventional troops have been, but in places like Africa, South America and Asia.

“Well, these guys aren’t run of the mill guys that we’re putting into this SFAB,” Milley said.

The all-volunteer brigade, save for the hand-picked officers, must have already served in a leadership role an operational unit before joining the SFAB.

They also have to score at least 80 percent on their PT test, submit to an interview and a board, maintain at least a secret security clearance, and be branch qualified for their MOS and grade.

“We’ve only accepted about 60 percent of those who have volunteered,” Milley said.

And there has been some special operations crossover, he added — one current battalion commander is a Green Beret, and another is on his way from the 75th Ranger Regiment.

While SFABs are not meant to take any prestige away from Army special operators, he added, Army leadership did feel that a beret and unit tab were appropriate.

“I think the mission of combat advising is a mission that I want to accentuate,” Milley said. “I want to make sure that those guys are recognized for that certain level of expertise.”

The first SFAB is due to deploy to to Afghanistan early next year, Milley said, as the second and third brigades prepare to stand up, The first two will be based at Fort Benning, Georgia, while the third is headed to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, he said.

“It’s not like they’re not earning it,” he said.

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.