Zaragoza, Spain — When On a sunny Wednesday afternoon, 23 Spaniards jumped out of a plane into the San Gregorio training area, they executed the static line jump tactics and procedures they’ve regularly trained, and landed on their home soil.

But they made the jump did it from a U.S. Air Force plane that took off from a U.S. Army base, used a U.S. Army parachute, and jumped with about 500 paratroopers from the 2nd Brigade, 82nd Airborne Division.

That type of interoperability was key to the massive exercise Trident Juncture 15, which just concluded in Europe.

During the exercise Trident Juncture, NATO military leaders have stressed interoperability, and the jump that capped a 13-nation, 1,800-troop showcase for media on Wednesday outside of Zaragoza was one example of ensuring that soldiers from different armies could work together if and when the alliance requires it.

"For the platoon that was with the American battalion, it was an experience like no other," said Spanish Capt. Guierrmo Alejandré, company commander for the platoon that jumped Wednesday.

Just as the jump represented a small part of the month-long, 30-nation, 36,000-troop Exercise Trident Juncture, it is the tip of the iceberg of U.S. and European airborne interaction. The allies see where there are similarities, and where there are For that reason, while there are differences that make these interactions worthwhile, the similarities may be more numerous.

"It’s pretty much the same," Alejandre. "With all the airborne units everything is pretty standardized," Alejandré said. "All the procedures are very strict, you have to go step by step, a jumpmaster checks the equipment."

There are differences in equipment and tactics, said a U.S. commander who finds perhaps the strongest parallel is the mentality of airborne soldiers across the globe.

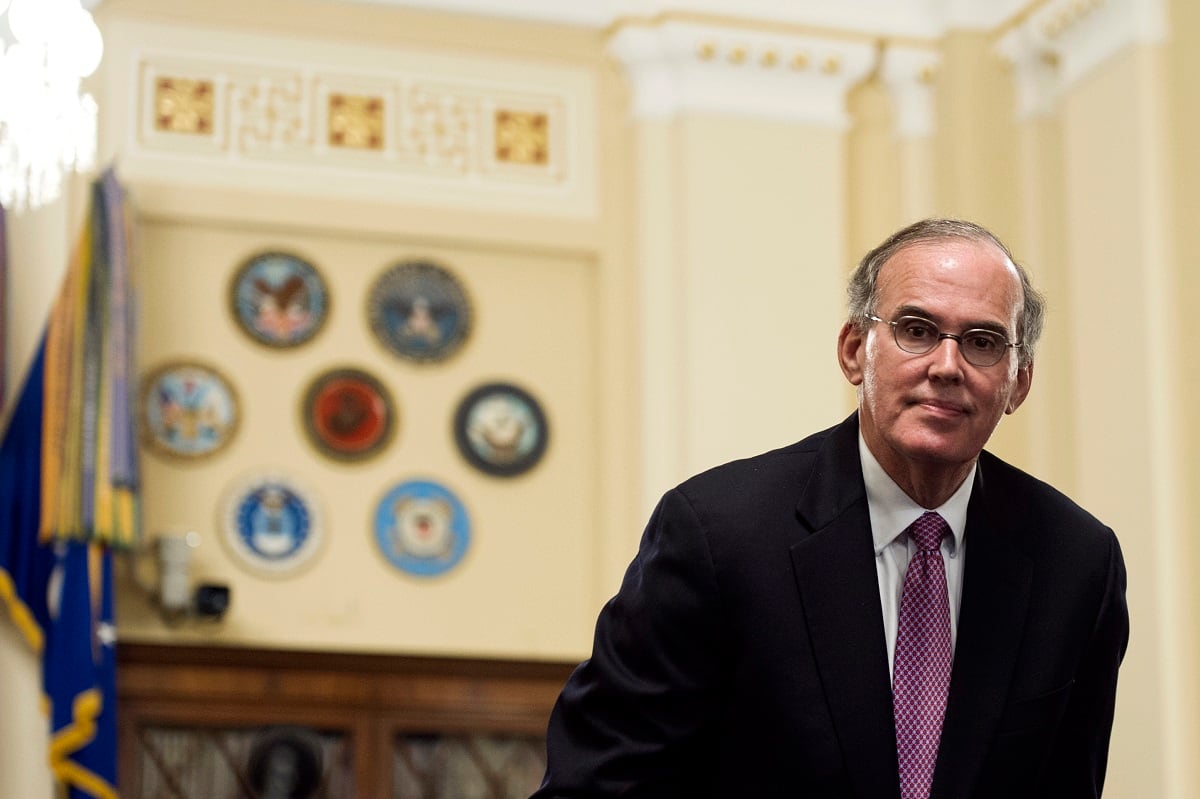

Col. Joseph Ryan, commander of the 82 Airborne Division's 2nd Brigade Combat Team, jumped with his troops at Exercise Trident Juncture on Nov. 4, near Zaragoza, Spain. He says trust is one thing that binds together paratroopers around the world.

Photo Credit: Daniel Woolfolk/Army Times

"It's the ethos. There's undeniably an inherent level of trust between international paratroopers that's unmatched," Col. Joseph Ryan, commander of the 2nd Brigade, told Army Times after parachuting into Spain with the rest of the group.

The Spaniards aren't the only nation the U.S. regularly works with regarding airborne coordination. British, German, Italians and many other armies in NATO have airborne units, though none as large as that of the U.S.

The 173rd Airborne Brigade, stationed in Vicenza, Italy, often works with European partners, for example. And the 82nd Airborne Division has had a visit from by Italy, the initial innovator of the static line jump before World War II, as recently as mid-September – a return visit after soldiers from the 82nd went to Italy in April.

Foreign military commanders say the procedures of jumping have largely been standardized over the years.

The biggest difference, based on multiple conversations, seems to be with the equipment, from plane to parachute.

Italian paratroopers, for example, jump with the T-10C, the third of four editions of the venerable parachute that dominated the Army from its inception after World War II until about 2010.

Spaniards use a model more like the T-10 as well, but as they demonstrated on Wednesday, their rucksacks work with the rigging of a T-11. (So far, just Australia has fully adopted the T-11, while the Canadians are in the process and other nations are considering it.)

In addition, the C-17 added a new dimension for the Spanish paratroopers. Spain's airborne brigade – it has a three-battalion readiness rotation – jumps from C-130s, a smaller aircraft with which Americans are familiar.

While the safety checks made by jumpmasters in flight may have felt familiar, the Spanish paratroopers weren't used to watching the jumpmasters leave the aircraft; Spain's army has them stay in the plane like safeties in the U.S. Army.

But Italian Col. Giuseppe Bertoncello, commander of the 187th Airborne Regiment, agreed with Alejandré.

"It's really difficult for me to find big differences when I'm talking with other light paratrooper units," Bertoncello said. "From my point of view, I stay focused on interoperability, ways we can incorporate with other units, and then obviously the task that follows depending on the situation, on the mission, the area."

The Bertoncello's paratroopers jumped with Belgium during another phase of Trident Junction in addition to its exchanges with the Americans earlier in the year.

Col. Joseph Ryan, commander of the 2nd Brigade, notes that the American paratroopers can count the Brits and Canadians among the several nation's they've trained with in the last six months. He said from both a jumping/equipment and a post-jump tactical standpoint, there are variances. But he finds perhaps the strongest parallel in the mentality of airborne soldiers across the globe.

"It's the ethos. There's undeniably there's an inherent level of trust between international paratroopers that's unmatched," Ryan told Army Times after parachuting into Spain with the rest of the group.

Ryan downplayed his unit’s importance as a small part in the broader NATO effort. But he effusively touted the capability – he said unique to the U.S. Army – to bring so many jumpers across an ocean and directly into a country.

He said his focus is on capability because it's critical to the deterrence sought by the alliance.

"It's a great opportunity for us to show what we can do on the global response force," Ryan said.