Maybe the medal was lost in the mail, or during a move.

Maybe the paperwork was never processed. Maybe the award was one of countless honors earned by soldiers during conflicts past – men and women more eager to return home than to track down missing decorations, rarely sharing details of their time in uniform. Maybe the details weren't shared, found instead in long-forgotten files after a family member's passing, prompting a new generation to seek recognition for a fading generation's service.

Then-Navy Lt. Linda Balink, left, poses with her aunt, now-retired Command Sgt. Maj. Ellina Spyker, during a 1970 visit to Fort McClellan, Alabama.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Linda Balink-White

And it's not just engraving and shipping. Team members help honorees and next of kin through the final stages of a process that can take several months, depending on the awards and records involved. That assistance can take many forms, from the correction of an errant claim number to the expedited processing of a request for an awardee in declining health ... even the occasional call to a local lawmaker, when putting a few medals in the mail doesn't seem like enough.

'We can do better than that'

The plan

"I'm sure that's what [Davis] would do for everybody," said Balink-White, whose career choice was influenced by her aunt's service. "It couldn't have been better."

"And I would say if the Army messed up," the retired Navy captain added.

Shop Supervisor Ron Henry Jr. retrieves a prestigious Medal of Honor from a safe in the Veteran Medals Program warehouse.

Photo Credit: Sgt. 1st Class Michael Zuk/Army

The daily grind

The eight-person VMP team includes engravers, assemblers and warehouse managers, all churning out 30,000 medals a year. They’re operating on about a four-month backlog, team supervisor Pat Weist said last month, but can get a request out much faster if circumstances require: The deteriorating health of a recipient, for example, or a high-level medal ceremony already on the calendar.

said last month, but can get a request out much faster if circumstances require: The deteriorating health of a recipient, for example, or a high-level medal ceremony already on the calendar.

"It's a very controlled item," Henry said. "It comes with its own flag, too."

Lost and found

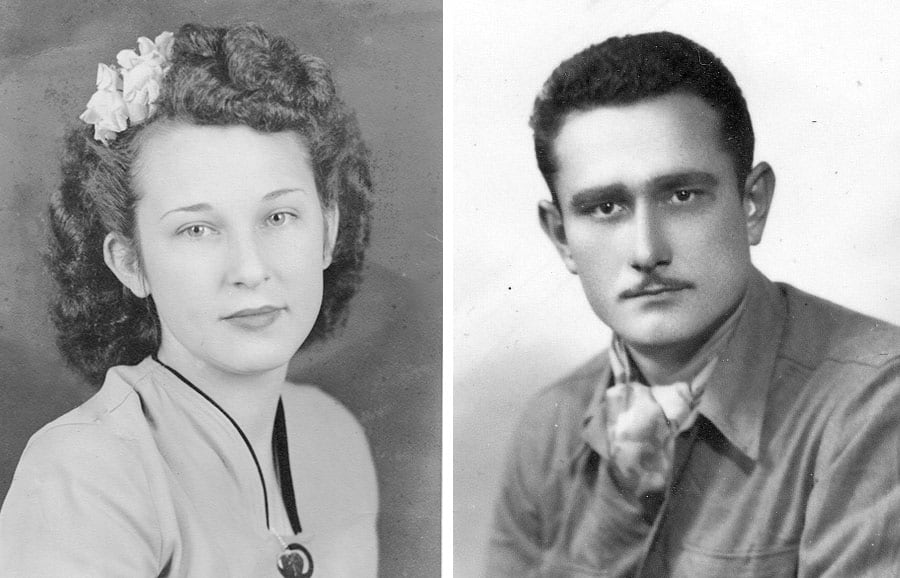

Al Davis Sr. (no relation to Tina Davis) rarely recounted his World War II experiences serving E Company, 357th Infantry Regiment, 90th Division, in France and Germany. His son, Al Jr.

(no relation to Tina Davis) rarely recounted his World War II experiences serving E Company, 357th Infantry Regiment, 90th Division, in France and Germany. His son, Al Jr. , did hear some stories from his mother, Belle

, did hear some stories from his mother, Belle , including those of his capture by German forces in March 1945.

, including those of his capture by German forces in March 1945.

Belle (Belisle) Davis and Al Davis Sr.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Al Davis Jr.

For instance, after his liberation by Third Army forces under Gen. George Patton, Davis received compensation for his time as a POW: A dollar a day, making the ordeal worth $13, total.

Davis died in 1971. Decades later, Al Jr. — oldest of seven children — learned of the Prisoner of War Medal, which had been authorized in the 1980s. He decided to apply for the honor on behalf of his mother, as well as inquire about replacing his father's Purple Heart, which had been lost in 2005 as the family evacuated in advance of Hurricane Katrina.

Staffers at the National Personnel Records Center found Davis Sr. had earned multiple honors beyond those two awards, including a Bronze Star and a Combat Infantryman Badge. The request reached Philadelphia, and when Davis Jr. sought a status update in June, Tina Davis responded.

"She contacted me and told me about how things would be delivered, and I told her that my mother was having a birthday in August, and if we could expedite things," he said. "She said that could be done, and they hopped on it. And then I received a note and a card."

Along with the medals, Tina Davis had shipped off birthday greetings to Belle, who turned 89, featuring a photo of some of the team members.

Belle Davis, with son Al Davis Jr., receives her husband's awards at Chateau Terrebonne, a nursing home in Houma, Louisiana.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Al Davis Jr.

He followed up with an email to the team: "I was humbled beyond measure to see my father's sacrifice honored in this way. I thank all of you immensely!"

Spreading the word

The stories continue, almost to the point of overload: The time a World War II veteran brought his original, slightly worn Purple Heart into the office and an engraver put the soldier's name on the back, on the spot. Or the time a woman contacted the office after running into a Purple Heart recipient on a flight to California — she wanted his name, which wasn't allowed, but Tina Davis tracked him down and sent him a replacement medal.

Or the times that requests come in from former soldiers whose current addresses may not accept certain deliveries.

"Prisoners — they get their awards," Davis said. "Once a soldier, always a soldier. I send them a letter and I ask them to send me an alternate address to send the awards to, because the prisoners aren't permitted to receive stuff like that."

Team members also man booths at veteran-friendly conferences, often becoming one of the more popular attractions when former soldiers learn how they can replace long-lost honors at a low price — Weist said the payment can be half of what a private vendor would charge, and simply covers the team's cost of restocking the medal.

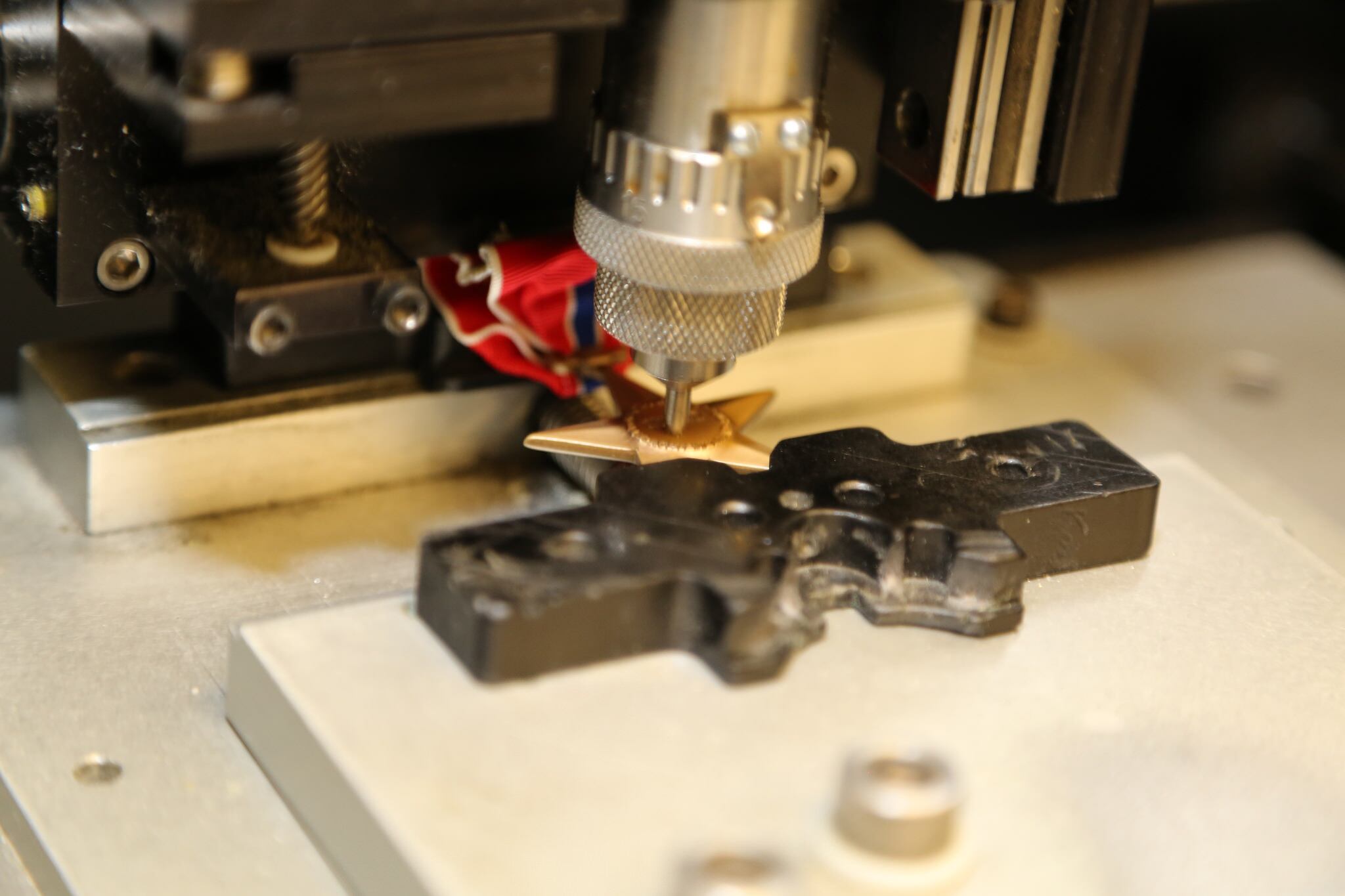

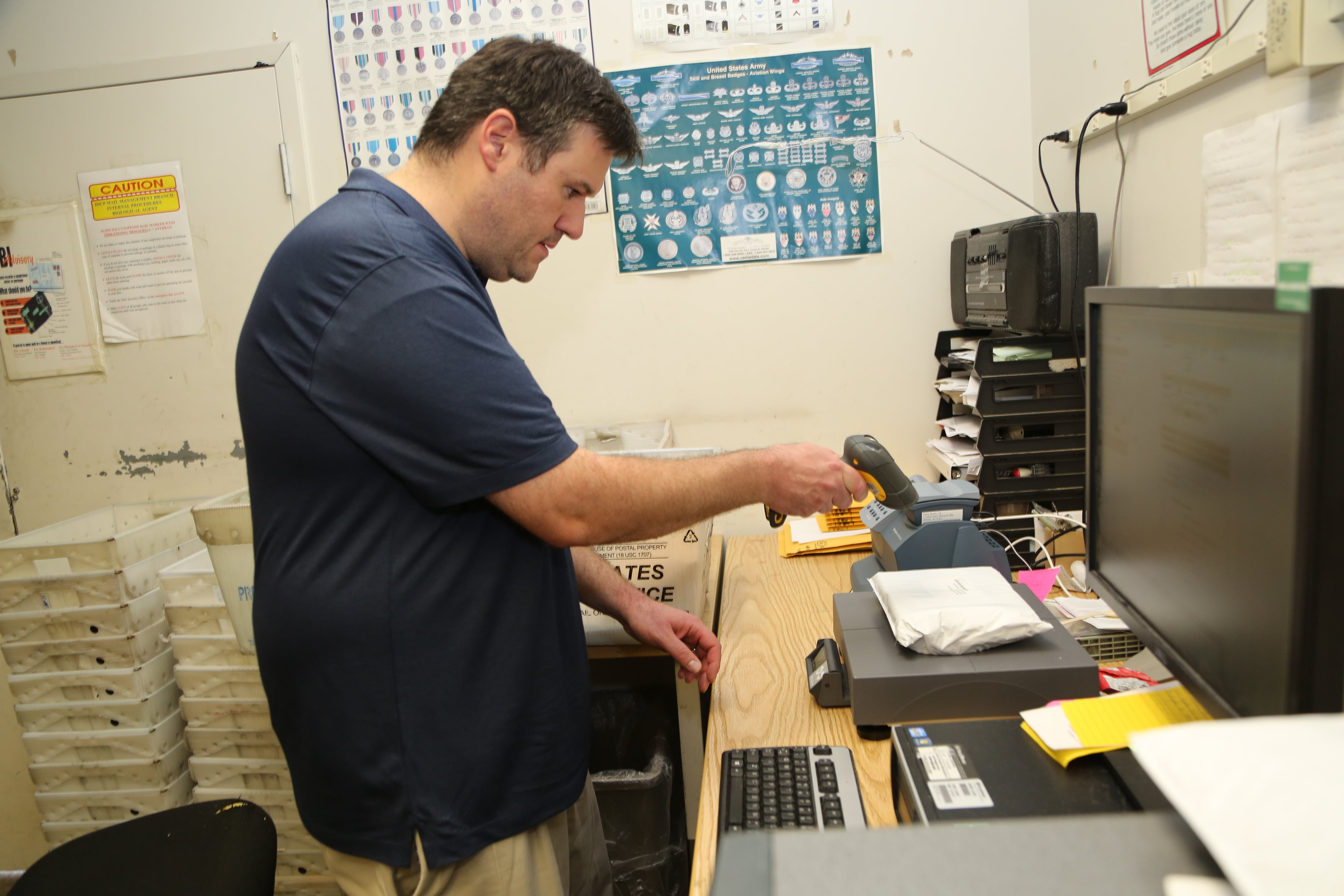

Engraver Joe Durkin processes a completed medals package ready to ship to the recipient.

Photo Credit: Sgt. 1st Class Michael Zuk/Army

"I am extremely proud of the team behind the effort who creates these special, heartwarming moments and lasting memories of service for our Army families," he said in a statement.

Awards 101

While the team fulfills medal requests, they are not the first stop for a soldier or a family member seeking the issue or re-issue of any honors.

Multiple websites are available to assist with such requests, but a good first stop, according to staffers at the National Personal Records Center in St. Louis, would be this information page maintained by the National Archives. It provides links where requests can be made online, and also printable forms such as Standard Form 180, Request Pertaining to Military Records.

Assembler Keith Thompson affixes attachments to a Vietnam Service Medal.

Photo Credit: Sgt. 1st Class Michael Zuk/Army

- Be specific. Identifying yourself as "next of kin" or "oldest surviving relative" may not be enough to fulfill Army requirements that limit award issuance to certain family members. Clearly state your relationship to the veteran in question.

- Be thorough. "If the veteran is living, we need to have the request signed by the veteran," Pratt said. "That’s pretty basic stuff, but it’s one of the things we run into all the time." Family members making requests in the name of deceased veterans must include proof of death — another step some applicants overlook.

- Be complete. The SF-180 provides a launching point for what can be a time-consuming process, as staffers sometimes must reconstruct records lost in a 1973 fire that consumed 80 percent of the Army’s personnel files for soldiers discharged from 1912 to 1959, according to Archives.gov.

- Be patient. Most requests take three to four months for NPRC to process and forward to the Army medals team, which has its own aforementioned backlog. Fire-related requests often take longer. Like the VMP, the NPRC can put a rush on requests involving veterans or family members in failing health, or other concerns that require a quicker turnaround.

For more on the Army's medal program, and to check on the status of existing medals requests, visit http://veteranmedals.army.mil/.

Kevin Lilley is the features editor of Military Times.