The type of explosions that would "jingle your earlobes down to your ankles" sent were the sounds that vitalized Sgt. Gerit Wasserman to running out of Ganci 2, Abu Ghraib, Iraq, on April 6, 2004.

It was one of the many mortar assaults from Iraqi insurgents on the prison during what news reports papers at the time called the "bloodiest month since the fall of Saddam Hussein" in 2003. Tensions were high, especially since a week prior, insurgents had beaten, burned and hung four armed contractors from Blackwater USA in Fallujah.

Wasserman, a pseudonym because he does not want to be identified, and about 100 other troops had come in as the transitioning unit in January 2004, when as the initial reports whispers of the Abu Ghraib large-scale scandal — depicting inhumane treatment and torture of prisoners being tortured — were was about to hit television screens around the world.

And the month of April politically, and literally, exploded.

"I said if I write this book, if I ever got to the point where it turns into a book, I want to make sure that there was a clear and distinct difference between our predecessors and us," Wasserman said of the soldiers who were involved in the mistreatmentlewd acts.

"Inevitably in the public's mind, our unit , the 391st battalion sort of got tarred with the same brush as our predecessors because even though we weren't there at the time of the incidents when they supposedly took place, we were there when it broke on the world news," he told Military Times.

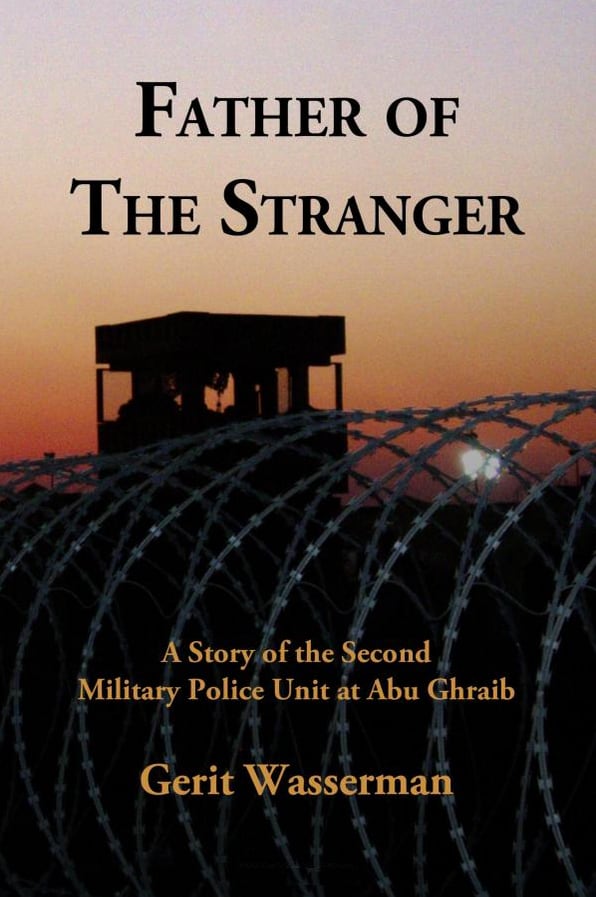

But the April attack, as then-Sgt. Wasserman remembers, and the bonds he forged fortified with fellow service members were what humanized his yearlong experience while serving with the 391st Military Police Battalion. Instead of moving on as a reservist in the 80th Division, Richmond, Virginia, to his coveted assignment at the drill sergeants' academy, Wasserman unexpectedly found a different side of himself, which he documents in his first book, "Father of the Stranger."

"What I've gotten out of this experience and the takeaway is that there is an opening at the end of the tunnel and somewhere outside of the opening there's a light," Wasserman said. "Being involved with such a heavy burden of violence changes you ," " It changes you in ways that you don't expect and we come back different. We feel different about things, we look at things differently. And in a lot of ways we're better."

"Father of the Stranger" is available on Amazon.com.

Wasserman gained various skills such as medical training and police experience from his time as a civilian auxiliary officer and used these experiences as he moved forward in his 24-year Army career between the National Guard and the Reserves. Wasserman retired in 2005. He and some members from the 391st have a reunion every year.

Editors note: Gerit Wasserman is a pseudonym. The names of members of their unit have also been changed in the book. The following interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

"Father of the Stranger" is the story of a year at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, in 2004 when tension was high and incoming U.S. soldiers were trying to get past the scandal there.

Photo Credit: Book cover

Q. When did events start to heat up in 2004?

A. In the beginning, things kind of seemed like they were going to stay calm for a little while. And then in the spring, the scandal that had been boiling and brewing up from the previous year eventually hit the news and it hit the news everywhere. And from about the end of March until the day we left we got attacked every single day in some form, shape or fashion. We fell under siege in a way. Trucks leaving our gate headed into Baghdad to pick up supplies were attacked. We saw images of trucks burning on the side of the road; those were our trucks burning on the side of the road. The insurgent forces were beginning to gain strength and get themselves organized and they began to see what we had felt was liberation was turning into occupation in their mind. Then this scandal hits the news and then we just — they said we're going to attack this place and get our people out of there and we were fighting it out every day.

Q. What was your day-today life like as an incoming MP guard?

A. The 391st MP battalion is a detention MP unit. They work with prisoners at the prison, which was about 300 acres. Our job was to guard and maintain the prison and do whatever it takes you know, to keep a prison running and that's what we did. We guarded prisoners, we fed prisoners, we gave them medical treatment. Whatever it is they needed We were guarding these prisoners as they were captured off the battlefields. But guarding them is guarding them under some extreme conditions, especially feeding and medical attention. Because it was feeding hundreds of people. It was giving them medical attention with very limited supplies at hand.

Q. What was the most vivid image you have of the April mortar attacks, specifically April 6?

A. We had people who had parts of their arms and legs blown off .There were guys that had the size of golf and tennis balls punctured in their back from 120mm or 80mm mortar. They brought out one injured detainee, still alive, to me. And I'm trying to get an IV in him and in my mind I'm screaming, "Where's this guy's vein? How do I stop the bleeding?" I look back at my platoon sergeant and he's kind of giving me the look to kind of move on., you know? I look back at this guy and he's dead. He died right there in my hands. He bled to death from his wounds. and his eyes aren't quite open and they're not quite closed; I had the IV set up and I just switched knees and inserted it right into another wounded guy's arm. In all, nine Iraqi detainees were killed and 98 wounded. For their actions, a few soldiers from the 391st MP Battalion received the Army Commendation Medal with Valor. They bravely stood their post during the attack, tended the wounded ... maintained control of the compound and ultimately saved lives.

Q. What story do you tell in "Father of the Stranger"?

A. Because of the scandal, that kind of gave the Army a little bit of a black eye at the time. And inevitably in the public's mind, that was our unit. But 90 percent of everything that's in this book, we all, my entire unit, experienced it. We all lived the mortar attacks. We all deployed from home somewhere whether they lived in Virginia or Ohio or Michigan or Florida; we all came from someplace. So 90 percent of this book is every guy that was with me. I just told one particular story from my perspective. But the public, the general population, doesn't distinguish between the two.

Q. This book took you almost 10 years to write. What was the challenge and what answers did you find?

A. As I was writing it it sort of turned into therapy. It sort of turned in a way to deal with my own emotions. and kind of sort them things out and figure out what I believe and what I didn't believe and what hurt me and what didn't hurt me. And as I went through the book, I went through each emotion. And as I began to deal with those emotions, I kind of figured me out along the way. And I know some people don't feel that way. They don't feel like they're better. They feel like they're lost or they feel like they're a broke toy, but that's not true. What I've gotten out of this experience and the takeaway is that there is an opening at the end of the tunnel. And if us soldiers and I say that collectively — Marines, sailors and airmen, too — if we kind of stick together and take care of each other the way we did over there and we help each other, we'll get through this together. But we've got to find something that diverts our energy and diverts ourselves in a positive way. Write a book, restore a car, finish your degree in something, go take part in local politics;Do Do whatever you've got to do to take all that energy and all that happened to you and aim it at something good and make that good happen. Whatever it is.