Shortly after the soldiers from 4th Squadron, 73rd Cavalry Regiment set out on patrol from Strong Point Payenzai, Afghanistan, a motorcycle carrying three Afghan men came into view.

Pfc. James Skelton reported the sighting to 1st Lt. Clint Lorance, his new platoon leader.

"He told me to engage," Skelton said, according to the transcript from Lorance's court-martial.

Skelton fired two shots. He missed. The motorcycle came to a stop, the men climbed off and began walking towards the Afghan National Army soldiers who were at the front of the U.S.-Afghan patrol.

"The ANA started telling them to go back, waving to them to return towards the motorcycle, to stay away," Skelton testified. "They turned around and went back towards the motorcycle."

Within seconds, two of them were dead. The third man ran away.

A gun truck that was accompanying the soldiers on foot had opened fire with its M240B machine gun.

"He was told to engage by Lieutenant Lorance when they had a visual," Skelton testified.

"Did he ask the vehicle what the men were doing?" the prosecutor asked.

"No," Skelton said.

"He just told them to engage?" the prosecutor asked.

"Yes," Skelton said.

One year after that fateful July 2, 2012, patrol, in a case that has been controversial from the start, Lorance was convicted of two counts of murder and one count of attempted murder.

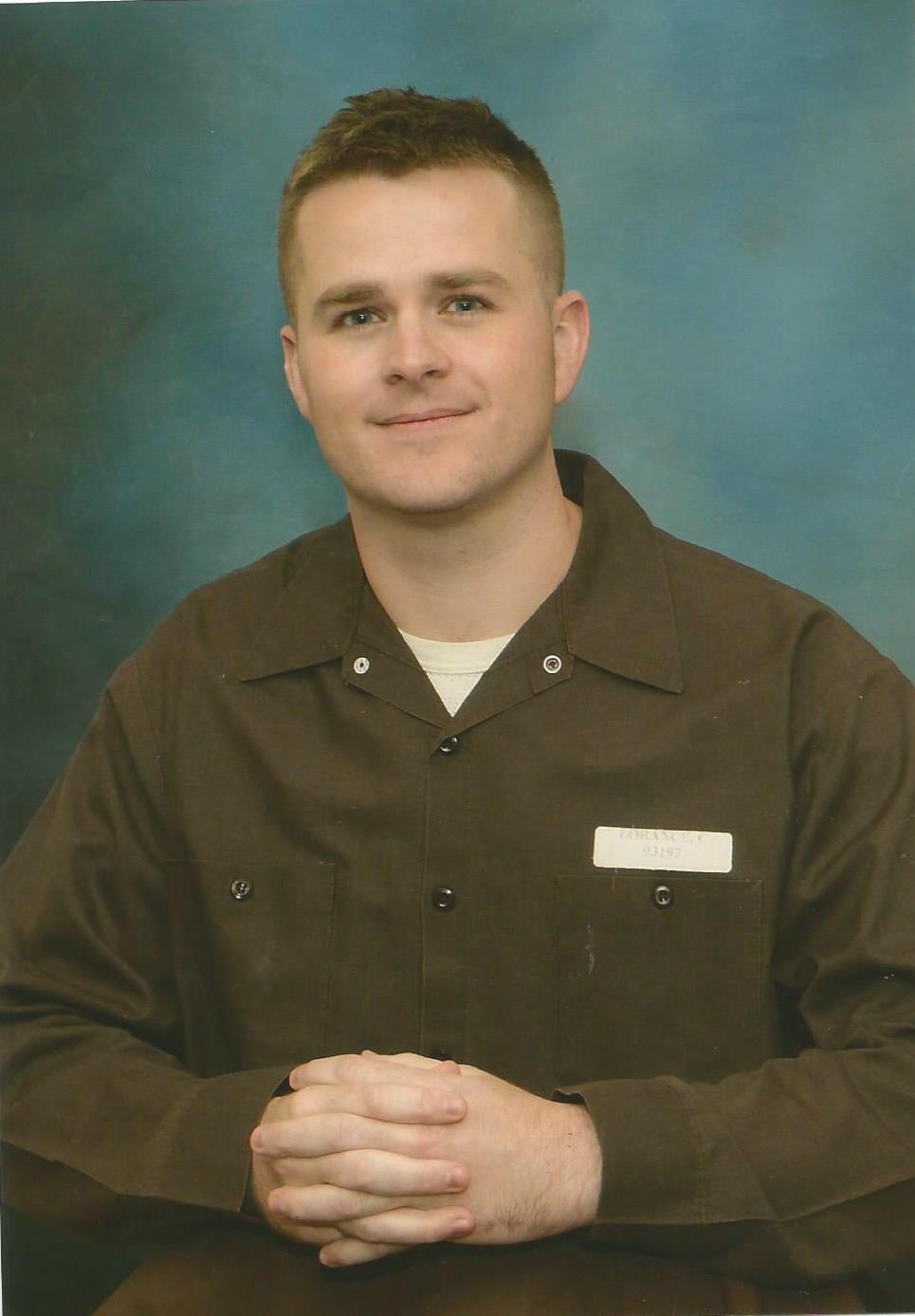

Lorance, now 30, is serving a 19-year prison sentence at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, but his case is far from over. Across the nation, thousands are rallying in hopes the baby-faced soldier can regain his freedom. They see him as a patriot, unfairly punished for actions taken to protect his fellow soldiers.

His own soldiers, however, paint a much different picture: They claim their platoon leader was ignorant, overzealous and out of control. That he hated the Afghan people and that he had spent recent days tormenting the locals and issuing death threats.

Lorance had a setback on Dec. 31, when the commander of the 82nd Airborne Division reduced Lorance's his sentence — but just by one year — and upheld the guilty verdict, effectively sending the case to the U.S. Army Court of Criminal Appeals.

"Maj. Gen. Richard Clarke carefully reviewed the facts of US v. Lorance, to include the clemency requests submitted in August, October, November and December 2014," said Maj. Crystal Boring, a spokeswoman for the XVIII Airborne Corps, in a statement. "After an in-depth study of the case, he upheld the guilty verdict from the court martial panel and directed one year off the original sentence of 20 years confinement due to post-trial delay."

Lorance's supporters, on a Facebook page called "Free Clint Lorance," railed against Clarke's decision and launched a White House petition that garnered more than 72,000 signatures in just seven days. It needs 100,000 signatures by Feb. 1 to get a response from the White House, and at this rate, it likely will reach that goal.

In the petition (found by searching "Clint Lorance" at petitions.whitehouse.gov), supporters call for a presidential pardon for Lorance.

"The president has the chance to tell the military and our enemies that when we send our young sons and daughters into harm's way, we do not turn against them," the petition states.

But as the fight for the young officer's freedom has gained traction online and on social media, Lorance's own soldiers are pushing back, they say, to make sure their side of the story is told.

Two sides of Clint Lorance

"All these petitioners need to be shown what kind of man [Lorance] really is," said a soldier who served as a team leader in Lorance's platoon, who asked to speak on background because he is still on active duty. "This isn't a soldier that went to war and gone done wrong. This is a soldier that had a taste for blood and wanted to have that fulfilled. And he did, but in the wrong way."

Todd Fitzgerald, a former specialist and infantryman in Lorance's platoon, said he felt betrayed by the lieutenant.

"I don't believe that he really understood what he was getting into," he said.

Fitzgerald testified during Lorance's court-martial.

"Us testifying against him, it wasn't a matter of not liking him, it wasn't a matter of any type of grudge or coercion," he said. "It was simply we knew that his actions, based on our experience, having operated in that area for months, were going to breed further insurgency. If you kill local citizens, they're no longer willing to help you."

Testimony from these solders is in stark contrast to how Lorance's mother, Anna, describes her son.

"I know he'd give his all to protect his men and serve this country. I just know him," she said. "To sit in that court, I was in total disbelief when the prosecutors were saying that as soon as Clint got his orders to replace that lieutenant, he was collecting all these maps and doing all this research instantly because he was planning to fabricate a war and get a medal. I wanted to scream at the top of my lungs."

It was difficult to hear "all these people tear my son apart," said Anna, who has fought tirelessly to exonerate her son.

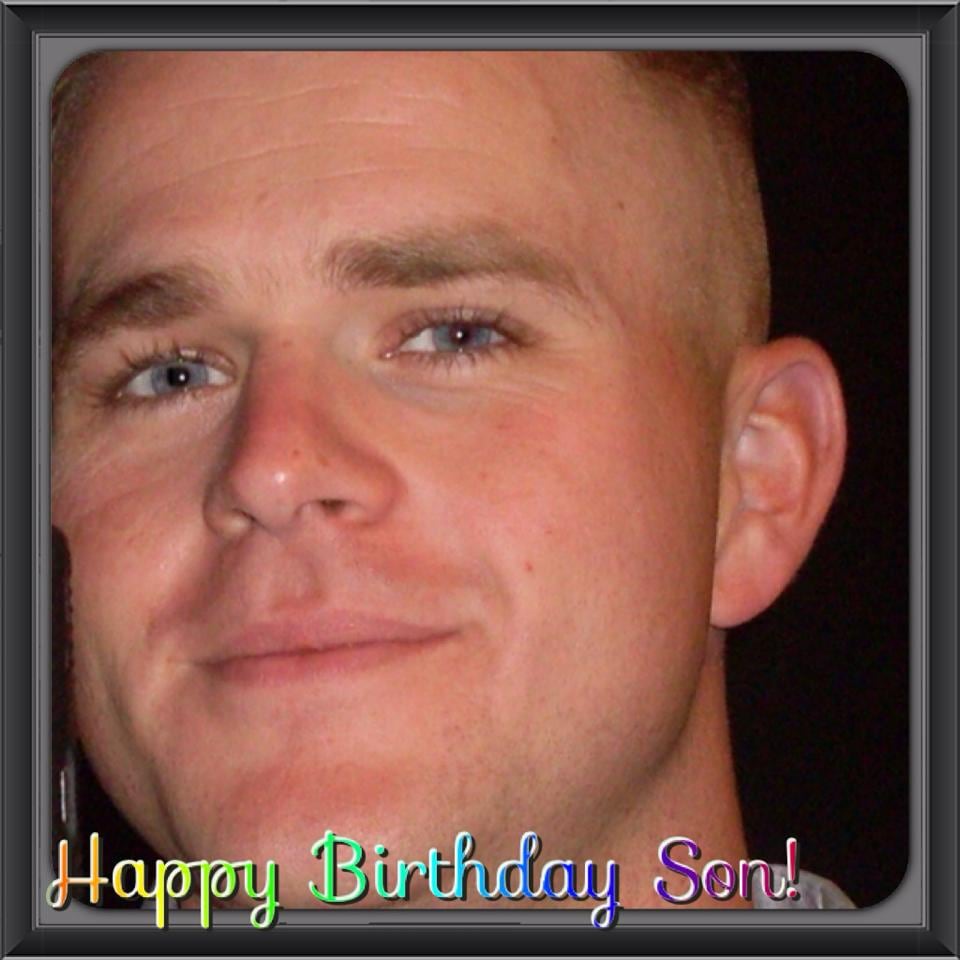

Posted Dec. 13 on Facebook: "30 years ago today God blessed us with our first Son, Clint! He has been a tremendous inspiration in our life. This is the second Birthday that he will spend in Leavenworth and I pray it is the last."

Photo Credit: Courtesy Free Clint Lorance

"He's always been the protector and the one who stood up for everyone else," she said. "If Clint could stand here today and talk on his behalf, one of the things he'd tell you, with pride, is 'I never left my soldiers behind.'"

When asked to respond to accusations against Lorance, the lieutenant's attorney John Maher, said the soldiers are "entitled to say anything they like," but said readers should be skeptical because the soldiers were granted immunity to testify. (While six soldiers did receive testimonial immunity, only four of them testified, according to trial transcripts. For this story, Army TImes interviewed three soldiers from the platoon who condemned Lorance's actions but had received no immunity).

"In the end, this case will not be resolved by comments made on social media by immunized soldiers," Maher said. "The real legal issue is that the government had and still has exculpatory and mitigating evidence that it was duty-bound to disclose. That the government did not disclose it means that the due process clause of the United States Constitution was violated. The Supreme Court has long held that the remedy for that violation is a new trial where due process is not violated."

Fight for a new trial

Maher said he is disappointed in Clarke's decision regarding clemency. He also said his client has grounds for a new trial.

"The defense has now identified information linking five of seven Afghan military-aged males on the field that day with terror," Maher said. "Because the government has always had that information and did not disclose it to the command or the trial defense counsel, examining 1st Lt. Lorance's decision-making takes a back seat. We never get to that question."

Basically, the government is obligated to disclose evidence that could negate guilt, reduce the degree of guilt or reduce the punishment for the accused, Maher said, citing the Rule for Courts-Martial.

"The first day at the Army JAG school, we're taught you turn over everything," said Maher, who also is a lieutenant colonel in the Army Reserve.

The government made a "serious legal error" by not turning over exonerating and/or mitigating evidence contained in government computer databases, Maher said.

"Before the government can take away any soldier's liberty, freedom, career, income, retirement, educational benefits, and full ability to get a job, the government must follow the rules," he said. "Here, it did not."

If that information had been turned over, the defense might have taken a different approach, or the case may not even have made it to trial, said Maher, who points out Lorance never fired his weapon that day.

"Clint did not initiate this, nor did he engage anybody directly," he said.

Though he didn't fire the weapon, he was convicted of making the call. He was also convicted of threatening a local Afghan; firing an M14 rifle into a village and trying to have one of his soldiers lie about receiving incoming fire; and obstructing justice by making a false radio report after the two men on the motorcycle were killed.

Before the incident

In the days leading up to Lorance taking over, his platoon had sustained four casualties, Maher wrote in his petition to Clarke. Among those wounded was Lorance's predecessor, who suffered shrapnel wounds to his abdomen, limbs, eyes and face when a hidden improvised explosive device went off.

The platoon was on high alert, Maher said, and when the motorcycle drove up his client had mere seconds to make a life-or-death decision in order to protect his men.

"This is not a case where a depraved soldier intended to kill indiscriminately," Maher said.

But Lorance's short tenure as platoon leader was rocky from the start, according to testimony during his court-martial.

Lorance, 28 at the time of the shooting, had enlisted in the Army after high school and served as a military police soldier in Iraq, South Korea, Georgia, North Carolina and Texas, according to Maher.

After returning from Iraq, Lorance was selected for the Army's Green to Gold program, and he was commissioned in 2010. He deployed to Afghanistan in February 2012 with 4th Brigade Combat Team, 82nd Airborne Division of Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

He served as a liaison officer for 4th Squadron, 73rd Cavalry for the first half of the deployment. He was tapped to lead 1st Platoon in the squadron's C Troop after its platoon leader was wounded.

"Over about a three-day period, Lieutenant Lorance … committed crimes of violence and crimes of dishonesty," said Capt. Kirk Otto, who prosecuted the case for the government, according to a transcript of the court-martial.

First, on June 30, 2012, Lorance threatened to kill an Afghan man and his family, Otto said in his opening statement.

The man, a farmer, and his child, who was about 4 years old, were at the gate to talk to the Americans about the concertina wire that was blocking access to his farm field, Otto said.

"He said, 'You move the c-wire, I'll have somebody kill you,'" Spc. James Twist, who was at the scene, testified during the court-martial.

Lorance then tried to have the Afghan turn in IEDs to the Americans, Twist testified.

"He was like, 'You bring us IEDs or we'll have the ANA kill your family,'" Twist said. "And Lieutenant Lorance was like, 'Well, if we ever come onto your land and we step on an IED or we find an IED, I'll have the ANA come and kill your family.' And he pointed to the kid and said, 'Do you want to see your child grow up?'"

The next day, Lorance directed one of the platoon's squad designated marksmen to fire his M14 rifle from one of the Strong Point's guard towers into the neighboring village of Sarenzai, Otto said.

"He directs harassing fire — illegal harassing fire — at villagers," Otto said.

Lorance directed his soldier to shoot near groups of people, as well as at walls and vehicles, he said. The soldier, Spc. Matthew Rush, refused to shoot when Lorance directed him to fire near a group of children, Otto said.

"These villagers were not doing anything," Otto said. "There was no demonstrated hostile intent. No one heard incoming shots."

The soldier who served as a team leader in the platoon, who spoke to Army Times on background, said he has pictures of Lorance on the rooftop.

"He was out of control," the soldier said. "We told him, 'Sir, I don't think it's a good idea.' He was like, 'Oh, it's a great idea. We're going to scare these guys so they actually attend our shura, and we won't lose anymore guys."

Lorance later tried to have Sgt. Daniel Williams, who was in the tactical operations center, falsely report that the Strong Point received incoming potshots, Otto said.

"He told me to report up that they had taken potshots from the village," Williams testified. "I told him that I wouldn't … because it's a false report. At least I thought so, sir."

Williams also testified that Lorance said "he didn't really care about upsetting them too much because he f**king hated them."

'Why isn't anybody firing yet?'

The next day, as the soldiers prepared to head out on a patrol, a small group of three or four Afghan men met them at the gate.

The men were upset. They wanted to know why the Americans shot into their village the day before.

Lorance told them that if they had a problem, they could attend the shura, or meeting, he planned to have later in the week, according to testimony. The Afghans refused to budge.

"He told them to get out of there," Skelton said in his testimony. "He started very aggressively yelling at them, and he started counting, and he pulled back the charging handle on his weapon and chambered a round."

As the soldiers' interpreter "panicked," one of the other soldiers testified, the Afghans turned away and left.

The Americans and a squad of Afghan National Army soldiers began walking out on their patrol.

Just moments into the patrol, Skelton opened fire on the motorcycle and then Pvt. David Shilo, operating the M240B machine gunon the truck, killed the two Afghans.

Fitzgerald, who left the Army in August, said he was standing near Lorance when the men on the motorcycle were hit.

"I remember him asking, 'Why isn't anybody firing yet?'" Fitzgerald said, adding that Lorance then took the radio and ordered the soldiers in the gun truck to open fire.

The men on the motorcycle stopped when Skelton first opened fire, Fitzgerald said.

"At that point, they were definitely not any type of threat," he said. "They weren't coming at us."

The patrol then pushed on into the village, where the bodies were quickly surrounded by crying and upset villagers.

First, Lorance prevented Skelton, who's trained to conduct battle damage assessments, including collecting biometric or personal data, from approaching the bodies, Otto said. He instead sent two other soldiers to search the bodies, Otto said. Those soldiers are trained to conduct the same assessments, but Skelton was the only one on patrol that day with the proper equipment, Otto said, according to the court-martial transcript.

Then, he falsely reported to his troop commander that he was unable to conduct a battle damage assessment because the bodies had already been removed, Otto said.

"Lieutenant Lorance ordered the murder of these two men," Otto said. "He knew it was murder, and that's why he took so many steps to try to cover it up."

The former team leader said he believes the three men on the motorcycle were the same men who came to the gate of the Strong Point to talk to the soldiers before the patrol.

"We were nowhere near the road when these guys were coming," the soldier said. "They weren't speeding toward troops."

The soldier also said he recognized the men when the patrol got to the village and came upon the bodies.

"We had been in that village so many times," he said. "We knew right then and there these were the village elders, these are the guys that actually matter in the village, and we just killed them."

The identities of the men who died that day remains in dispute. Some of the soldiers there that day say at least one was the village elder, while Lorance's lawyer argues the prosecution never named the men in court or in the charging documents against his client.

The former team leader said the platoon never recovered from the July 2 incident.

"We were family, and he split our family up," he said. "We have gone through so much shit because of this dude. We didn't ask for this. We didn't want this. He wanted to see contact, he wanted to be out there, and he f**ked up, and he should pay for it."

Another soldier from Lorance's platoon, who also asked to remain anonymous because he feared he might get in trouble, said the men who had been killed were wearing the same color clothes as the villagers at the gate.

"I feel like he was out for blood," he said about Lorance. "Three days prior to that incident, [a soldier from the platoon] got shot in the neck. I felt like he went in there and wanted to prove to us that he wanted to take care of us."

The soldiers on the patrol were upset as they returned to their Strong Point, Fitzgerald said.

"No one was really talking," he said. "We'd look at each other, and there was just a mutual feeling that what just happened was wrong, very wrong. There was a heavy feeling. I personally felt betrayal."

Fitzgerald said he was not coerced into testifying at Lorance's court-martial. He also didn't receive immunity from prosecution in exchange for his testimony, he said.

"I wasn't facing any charges, I wasn't offered any incentives, I wasn't threatened with any negative action," he said.

It was difficult to testify against Lorance, Fitzgerald added.

"I didn't know Clint at all," he said. "I met him and he was with us for a few days. Since then, I've seen things his family said about him. There are a lot of people who have a lot of good things to say about him. I stand by my testimony, but I do understand that his family, they're victims, too."

Since his sentencing, Lorance has been pursuing a master's degree via correspondence and is on a self-designed reading program to keep his mind sharp, Maher said. He exercises daily, eats a healthy diet and remains "very spiritual," Maher said. Ultimately, Lorance wants to earn a doctoral degree and teach, he said.

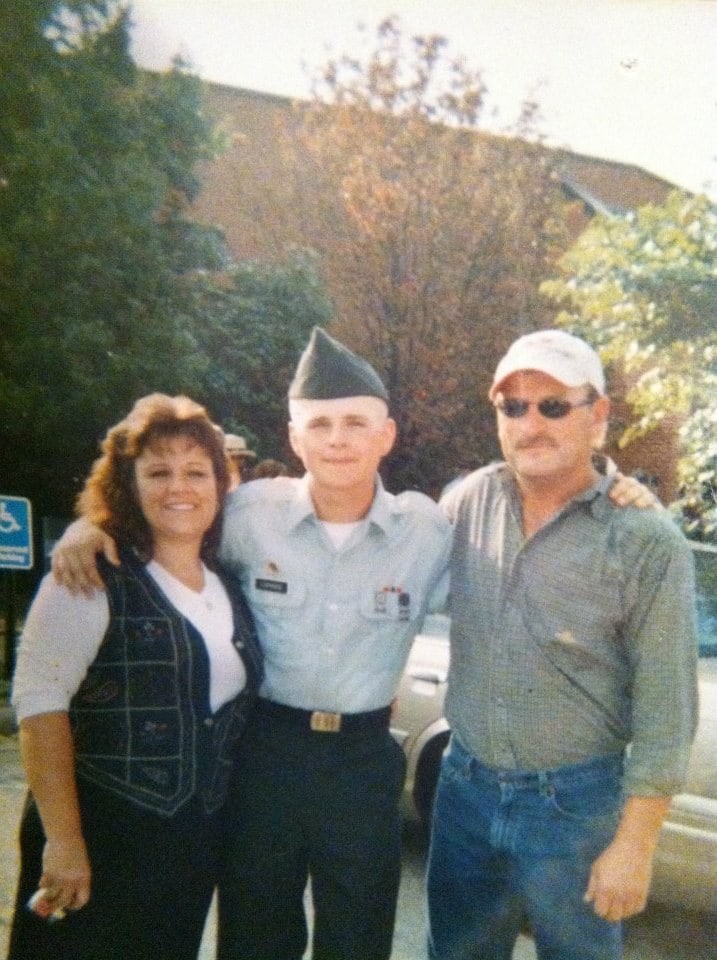

Clint Lorance at his basic graduation with Anna, his mom, and Tracey, his father.

Photo Credit: Courtesy Free Clint Lorance

"He's very humble," he said. "He doesn't appear to have any resentment or anger."

Anna Lorance, who tries to visit as often as she can, agreed.

"He is remaining very true to his character," she said. "He's a strong, positive young man and has been all his life. He is still being a leader inside those walls, reaching out to help everybody he can, encouraging those that he can."

Her son is convinced he did the right thing that day in Afghanistan, Anna Lorance said.

"He said, 'I can do prison, but I could never have looked those mothers in the face and told them their sons are no longer alive because I didn't do my job,'" she said. "'Then I'd be in a different prison for the rest of my life.'"

Her son would never have seen the inside of a prison cell had he not served his country, Anna Lorance said.

"It's totally unfair, but we'll get through this," she said.

Michelle Tan is the editor of Army Times and Air Force Times. She has covered the military for Military Times since 2005, and has embedded with U.S. troops in Iraq, Afghanistan, Kuwait, Haiti, Gabon and the Horn of Africa.