Retired Lt. Col. Dick Cole, the last surviving member of the Doolittle Raiders who rallied the nation’s spirit during the darkest days of World War II, has passed away.

Tom Casey, president of the Doolittle Tokyo Raiders Association, confirmed to Air Force Times that Cole died Tuesday morning in San Antonio. His daughter, Cindy Cole Chal, and son, Richard Cole, were by his side, Casey said.

Cole will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery, Casey said. Memorial services are also being scheduled at Joint Base San Antonio-Randolph in Texas.

Cole, who was then-Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle’s co-pilot in the No. 1 bomber during the daring 1942 raid to strike Japan, was 103.

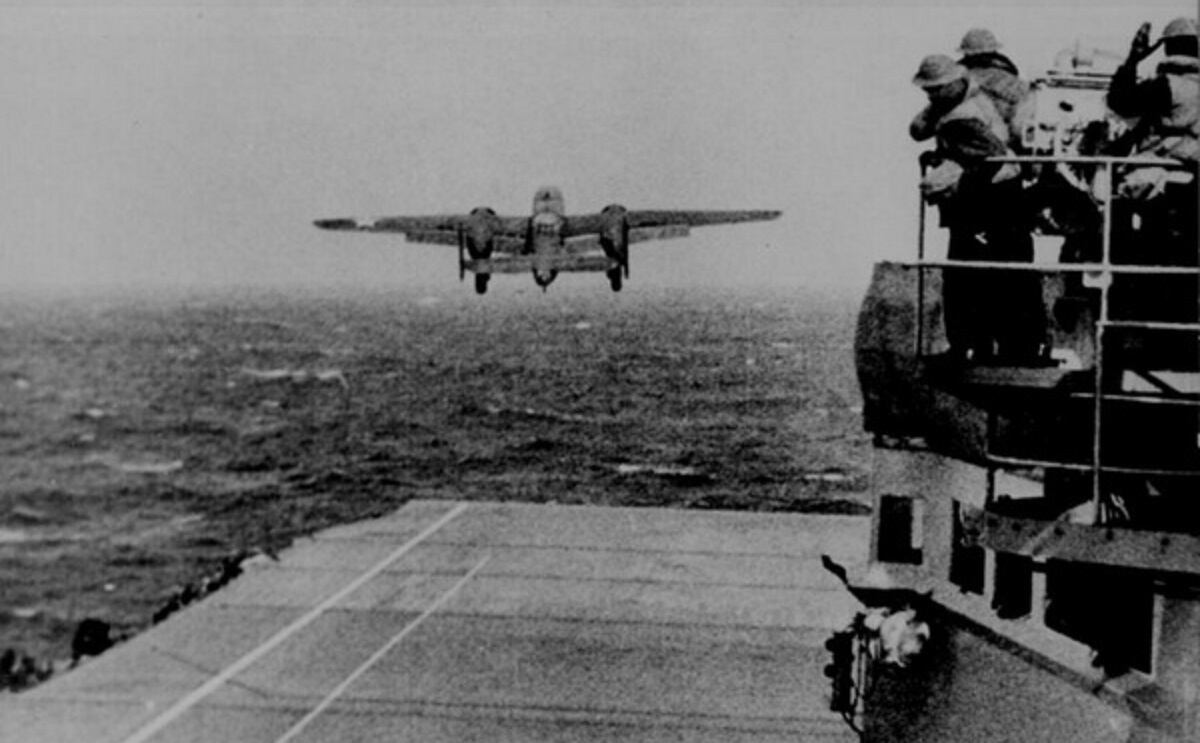

The Doolittle Raid was the United States’ first counterattack on the Japanese mainland after Pearl Harbor. Eighty U.S. Army Air Forces airmen in 16 modified B-25B Mitchell bombers launched from the aircraft carrier Hornet, about 650 nautical miles east of Japan, to strike Tokyo. While it only caused minor damage, the mission boosted morale on the U.S. homefront a little more than four months after Pearl Harbor, and sent a signal to the Japanese people not only that the U.S. was ready to fight back but also that it could strike the Japanese mainland.

Cole’s influence is still very apparent in today’s Air Force, and he remains a beloved figure among airmen. In 2016, he appeared on stage at the Air Force Association’s Air Space Cyber conference to announce that the service’s next stealth bomber, the B-21, would be named the Raider. Hurlburt Field in Florida in 2017 renamed the building housing the 319th Special Operations Squadron the Richard E. Cole Building.

And when he turned 103 last Sept. 7, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Dave Goldfein and his wife, Dawn, called him to wish him a happy birthday.

Cole was born and raised in Dayton, Ohio. In a 2016 interview with HistoryNet.com, Cole said he first became interested in flying as a kid, when he would ride his bicycle to the Army Air Corps test base McCook Field and watch the pilots fly. He said he enlisted in the Army Air Corps in November 1940 because “it was a good job,” especially in the midst of the Great Depression, and after finishing training went to the 17th Bombardment Group at Pendleton, Oregon.

He was transferred to Columbia, South Carolina, in early February 1942, where he saw a bulletin board notice seeking volunteers for a mission. His entire group put in their names.

“Everyone wanted to go on that mission,” Cole said in a 2017 Air Force release.

Cole, who was then 26 years old, trained at Eglin Air Field in Florida for the secret raid.

“We were confined to base, in isolated barracks, and told not to talk about our training,” Cole told HistoryNet. “We knew it would be dangerous, but that’s all.”

The B-25 typically needed about 3,000 feet to take off, Cole said, but they trained to get airborne in 500 feet. And when future Navy Admiral Henry Miller started teaching them how to take off from a carrier, they guessed they were headed to the Pacific to take the fight to Japan.

Then-2nd. Lt. Cole became Doolittle’s co-pilot by chance, when the pilot he had been training with fell ill. Doolittle’s intended co-pilot also became unable to fly.

The B-25s were stripped of all excess equipment, including their bombsights and lower turrets, and loaded up with extra fuel tanks that doubled capacity to about 1,100 gallons. They left port from Alameda, California, on April 2, 1942, and two days later were told they would strike Tokyo.

“We were pretty excited — above all, happy to know what we were going to do,” Cole said. “Things quieted down as people began to realize what they were getting into.”

After the Navy ran into a Japanese picket ship, Navy Adm. William “Bull” Halsey decided to launch the mission earlier than planned. Conditions were rough, Cole told HistoryNet — water came over the bow, and the planes started to slip around the deck. But the wind about doubled the carrier speed of 20 to 35 knots, which helped the planes get airborne.

They reached Japan after a little more than four hours, flying at an altitude averaging roughly 200 feet, Cole said. When Doolittle and Cole neared Tokyo, it was bright and sunny. Doolittle pulled up to 1,500 feet, and bombardier Fred Braemer — then a staff sergeant — dropped the bombs. Cole said they “got jostled around a bit by anti-aircraft” fire, but didn’t think they got hit.

Doolittle’s crew intended to land in Chuchow, China, fuel up, and continue to Western China, but they hit a snag. They ran into a severe rainstorm with lightning. Cole said the Chinese also heard their engines and thought they were Japanese, so they turned off the electric power to the lights. The crew had no choice but to fly until they ran out of gas and then bail out, he said.

Cole’s parachute got stuck on a pine tree, 12 feet above the ground. After freeing himself, he walked west to a Chinese village. Cole rejoined the rest of the crew, who also bailed out successfully, and they were picked up by Chinese troops.

He continued serving in the China-Burma-India Theater until June 1943, and then volunteered for Project 9, which led to the creation of the 1st Air Commando Group.

Cole said that Doolittle feared his audacious mission had failed, because all planes and some of his airmen were lost. Three airmen died bailing out, and eight others were captured by the Japanese.

But in 2016, Cole said the raid was “a turning point in the war.” Though the 16 bombers didn’t cause much damage, their actions prompted the Japanese to pull back its forces from Australia and India to shore up the Central Pacific, he said, and they transferred two carriers to Alaska, where they thought the raid had originated, which evened the odds for the Navy at Midway.

“Japanese naval forces were at a disadvantage from then on,” Cole said.

The raid also had two other goals, Cole said: First, to show the Japanese people that despite what their leaders told them, Japan could be bombed from the air. And second, “to give the Allies, and particularly the United States, a morale shot in the arm.”

Cole and the other Raiders received the Distinguished Flying Cross, and Doolittle received the Medal of Honor.

“He deserved a lot more,” Cole said of Doolittle. When asked what he thought of his commander, Cole said, “the highest order of respect from one human being to another.”

When Cole retired, his list of decorations included the DFC with two oak leaf clusters, the Bronze Star, and the Air Force Commendation Medal. In 2014, President Obama presented Cole and three other Raiders the Congressional Gold Medal at the White House.

But Cole said the Raiders didn’t feel like heroes.

“We were just doing our job, part of the big picture, and happy that what we did was helpful,” Cole said.

David Lauterborn of HistoryNet.com contributed to this report.

Stephen Losey is the air warfare reporter for Defense News. He previously covered leadership and personnel issues at Air Force Times, and the Pentagon, special operations and air warfare at Military.com. He has traveled to the Middle East to cover U.S. Air Force operations.