Over the past three decades, the number of veterans involved in extremist crimes has shot up 350%, according to data from the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism. So why are veterans getting wrapped up in extremist ideology, what makes them vulnerable and how can the multiple government agencies they associate with prevent it?

The VA, for example, has long known that separating service members are at a particular risk, as they transition from a regimented lifestyle with a clear purpose to a civilian world where everything is open to them. Groups prey on that desire to belong, to serve a cause.

“The vulnerability side is what happens when they get targeted with propaganda,” Cynthia Miller-Idriss, who heads American University’s Polarization and Extremism Research and Innovation Lab, said Friday during a Brookings Institution event,” and that propaganda and the manipulation of the values that attracted a lot of folks to volunteer in the first place, includes rhetoric that’s laden with appeals to ‘brotherhood,’ defensive ... a chance to be a part of a meaningful cause.”

At the same time, Americans in general are more distrusting of the structures they once believed in, from the military, to Congress, the presidency and the media.

“Now, the challenge, I think, that we have right now is that we’ve lost a lot of faith in those institutions, as Cynthia was talking about,” said Scott Cooper, Marine veteran and founder of the Veterans and Citizens Initiative. “When it becomes patriotic to be against your government, then there’s a problem there ... what we’ve seen is that some of that rhetoric that Timothy McVeigh consumed is now becoming mainstream.”

For someone who has built an identity around serving the nation and protecting their fellow Americans, there can be an opening for extremist groups who purport to offer that.

“... but in ways they get twisted, often arguing that they’re called upon to defend the country against traitors, tyrannical leaders, and trying to convert a sense of betrayal or anger at the government, or at mainstream society, into mobilization to violent action that’s framed as heroic defense of the real or the true nation,” Miller-Idriss added.

In turn, those extremist groups get members with tactical and mission-planning experience, as well as the clout of implicitly respected veterans among their membership.

RELATED

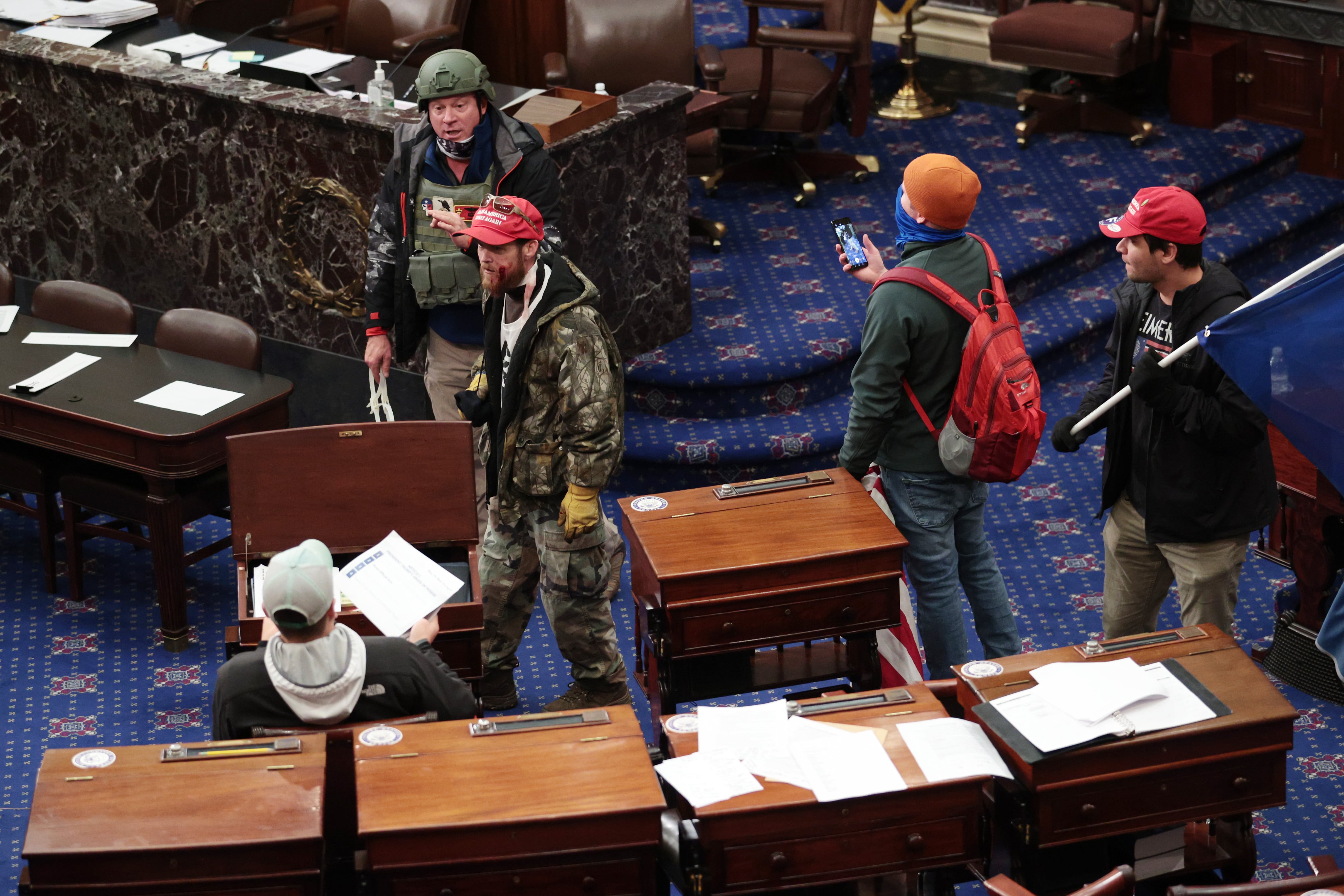

Though stories of service members and veterans engaging in violent extremist rhetoric or activity have popped up here and there in recent years, the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol brought the issue into sharp focus for the Defense Department ― particularly when arrest records began to reflect outsize participation by either current service members or veterans.

Following a one-day stand-down in which every unit in the military sat through a presentation about extremism, of varying thoroughness, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin stood up a working group first tasked with creating a definition for extremism, as well as reviewing how the department might better screen recruits for extremist leadings and educate transitioning troops about potential recruitment on the other side.

A progress report was due in July. As of late October, it is complete, but Pentagon spokesman John Kirby hasn’t been able to say when Austin will meet with the working group to discuss it, or when the findings might be released publicly.

Though the new extremism definition is expected to go beyond the current instruction, it’s unlikely that membership in any group will be prohibited, as that would require DoD to make a list of prohibited groups ― an exercise that would surely bring deep political backlash.

“In our lab, we define extremism as a way of thinking that positions the world unto us versus them, such that the other group poses an existential threat to your own group, that typically has to be thwarted with violence, and then often with the framing of it being heroic violence to save your people, right,” Miller-Idriss said Friday. “So it’s not just an all-negative thing, but often framed in positive ways that are about saving your people.”

For good reason, she said, the federal government tends to focus on preventing violence in its counter-extremism research and policy, so as not to step on anyone’s First Amendment rights.

“And that’s important,” she said. “But I also think that we have to recognize that things like disinformation and propaganda and hate speech are precursors to violence. They can lead to the incitement of violence, and ... there’s a role to play in protecting democracy and making it more resilient from within.”

The working group is also meant to explore ways that DoD can get a better handle on the incidence of extremist ideology in the force. Some of that will come through research, particularly collaborating with other groups who are experienced in it.

“We produce these large datasets on individual-level behaviors, and mobilization to violence,” William Braniff, who directs the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, said Friday. “We’ve identified both protective factors [and] risk factors that are that are statistically valid, and the insider threat hubs within the Department of Defense use those data to try to help screen.”

But it will take a wider approach to do anything about it. For DoD, they can provide training to prevent incidents and discharge anyone who violates policies, but that doesn’t remove the threat to the general public.

“It’s good if you can identify someone, but it’s not sufficient,” he added. “You then have to provide wraparound services for that individual to de-risk them. If we merely eject that person from the ranks, they just become the local law enforcement and local community’s problem, and you don’t even really de-risk the situation.”

The VA is also part of the discussion, and may have a role to play. The challenge will be that, while the VA is accessible to veterans, it’s not really set up for this kind of work. It’s mostly focused on health care services for individual veterans, rather than training or community-building that might help steer veterans away from extremist groups.

The mandate of the VA isn’t necessarily going to change, Shawn Turner, the VA secretary’s adviser for strategic engagement, said Friday, but they are interested in having a role.

“And I think as part of our effort to take care of them, we need to make sure that as Cynthia has said, as Scott said, as Bill said, said that we give them the tools to recognize if they’re being targeted by these extremist group,” he said. “And when these groups break through, when they break through these veterans, and these veterans are on a path to violence, we at the VA to make sure that we’re there for them.”

While concerns about veterans and extremism has mostly focused on protecting the public from violence, there is another facet to consider, Braniff said.

“Overall, numerically, this is a small but growing problem. But it’s not just a numbers problem. It’s also a national security concern,” he said. “If the military veteran brand is sullied, who’s going to join that all-volunteer military in the future? If servicemen and servicewomen and families put ideology, party first, it undermines the premise of civilian control of the military.”

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.