From its first days on the flight line, the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter had to overcome a reputation that it was too expensive and too delicate.

Detractors complained that the fifth-generation jet couldn’t dogfight as well as legacy aircraft, was years delayed and billions over budget and was hindered by finicky software and a complicated maintenance system.

But when the F-35 showed up to support friendly forces in Afghanistan, the response was far different.

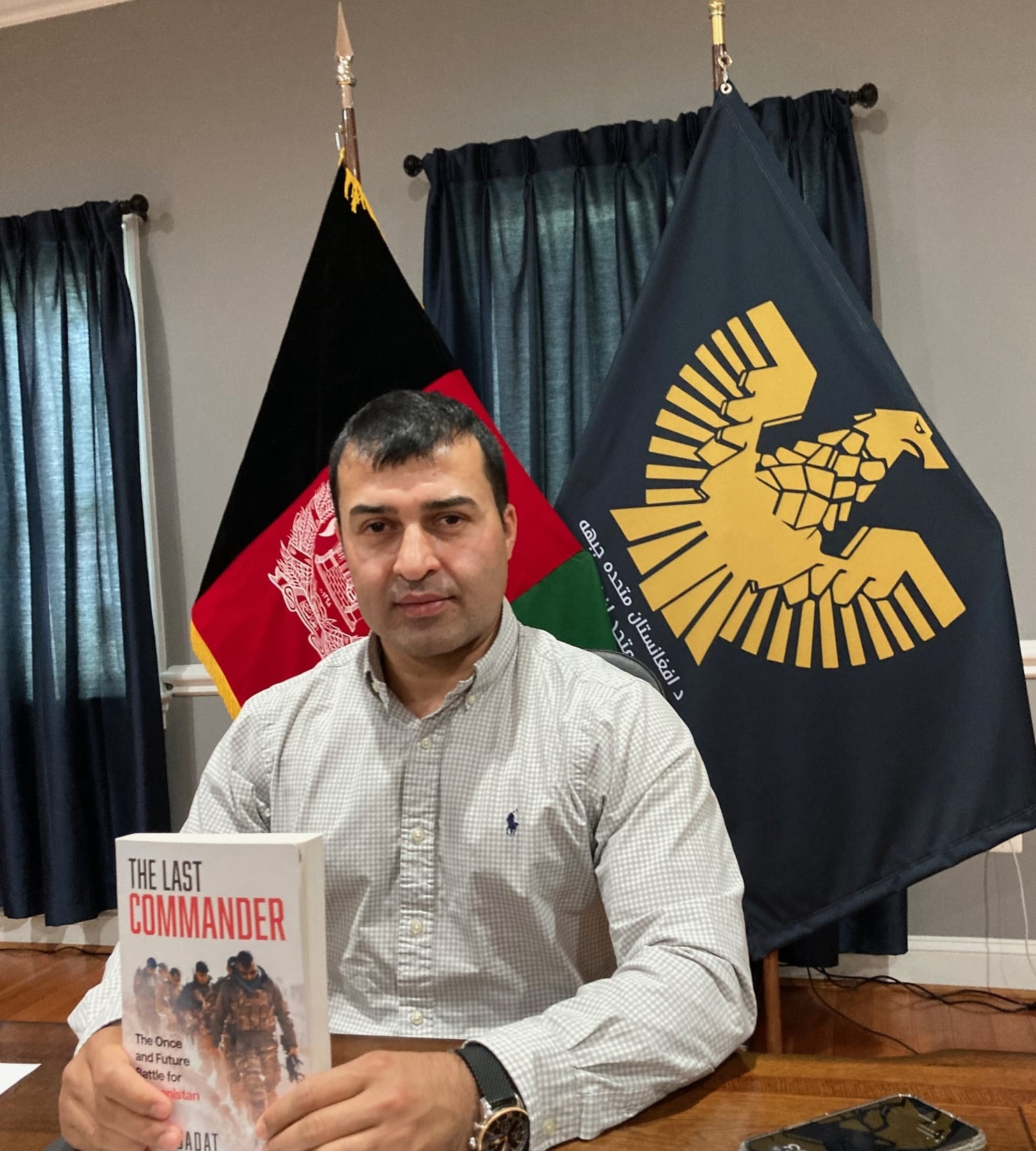

In his book “The Last Commander,” released this summer, Afghan Lt. Gen. Sami Sadat gives a first-of-its-kind account of an early F-35 mission, shortly after the jet began deploying to Afghanistan for the first time.

Sadat, who was the last person to command Afghan National Army forces in Afghanistan prior to the fall of the country’s government — amid the 2021 U.S. military withdrawal — describes a platform so new and secretive it needed a codename. It also displayed a capability that made his troops marvel.

While Marine Corps F-35Bs flew the platform’s first combat mission in Afghanistan in 2018, coming off the amphibious assault ship Essex to hit a target in support of ground clearance operations, the planes would remain a rare sight over the country, with U.S. troops routinely calling on familiar platforms like the F-16 Fighting Falcon and A-10 Thunderbolt.

But when Sadat and his ground commanders were working to clear out Taliban strongholds in mountainous southwestern Afghanistan in the winter of 2019-20, they found themselves in need of a capability the A-10 couldn’t supply.

During an operation to protect the Salma Dam, located in Herat province, from Taliban destruction, one detachment of Afghan troops became stuck as they pushed north, Sadat writes in his book. Cloud cover in temperatures plunging below zero made it impossible to conduct air strikes against the Taliban using U.S.-supplied A-10s.

“That’s when we made the first use in Afghanistan of a weapon which would give us a significant advantage in winter fighting,” Sadat recalls.

He described a conversation with U.S. Air Force Maj. Michael Martin, then deputy commanding general of Special Operations Joint Task Force-Afghanistan. Martin said he had access to a plane that could solve Sadat’s problems.

RELATED

“Sami, I can’t tell you the type of aircraft we are employing, but it can bomb accurately through clouds,” Sadat remembers Martin telling him.

In response, Sadat suggested a code name: “Cool Birds.”

The name stuck, and a nighttime strike mission was authorized. An Afghan major general confirmed grid references and gave the mission verbal assent.

“But he was confused,” Sadat writes. “He could hear no planes. He had no idea of the capability of the F-35s.”

Minutes later, he got a call from the general, shocked that the strike had taken place — as evidenced by loud booms and the disappearance of the Taliban threat — all without even hearing the stealthy F-35s approaching, Sadat writes.

“And so, through confident patrolling village after village through the snow, allied with the most sophisticated technology available on any battlefield, we turned the winter to our advantage,” Sadat’s account reads. The Americans, he added, “were glad of the opportunity to test their capability in real conditions.”

In an interview with Military Times, Sadat, who now lives in northern Virginia, expanded on his story, saying the event left a lasting impression on the Afghan troops.

“The impact [the F-35] left on my soldiers was amazing. Like, whoa, you know, we have this technology,” Sadat said. “But also the impact on the Taliban was quite crippling, because they have never seen Afghan forces move in the winter, and they have never seen planes that could bomb through the clouds.”

Sadat said he was so concerned about the risks Afghan ground forces were taking during the winter operation that it left him with physical pains in his stomach during missions.

But “everything worked out,” he said, “in an extraordinary way.”

One of the most heralded features of the F-35 was its distributed aperture system, comprising six sensors around the perimeter of the plane. Paired with a $400,000 helmet, the system allowed pilots to “see through” the plane and essentially have a 360-degree view of their surroundings.

These tools, according to the Air Force, enable “positive target identification and precision strike in all weather conditions.”

As for the Afghan military forces, despite what Sadat describes as a series of victories against the Taliban in 2019 and 2020, he writes that forward momentum was hindered by the 2020 Doha Agreement’s peace negotiations with the Taliban.

That agreement, he said, weakened the Afghans’ offensive capability and limited the U.S. military’s capacity to support their missions. Then, when Kabul fell in 2021, Afghanistan’s military scattered and fled.

Sadat is planning a tour for his book in part to raise awareness and support for the Afghanistan United Front, an organization he founded that is currently working on a strategy to overcome the Taliban and return the country to a democratic government.